Can it be for God when it’s for a grade?

Orthodox schools across the country try ways to teach learning for its own sake, but most students still think grades are necessary

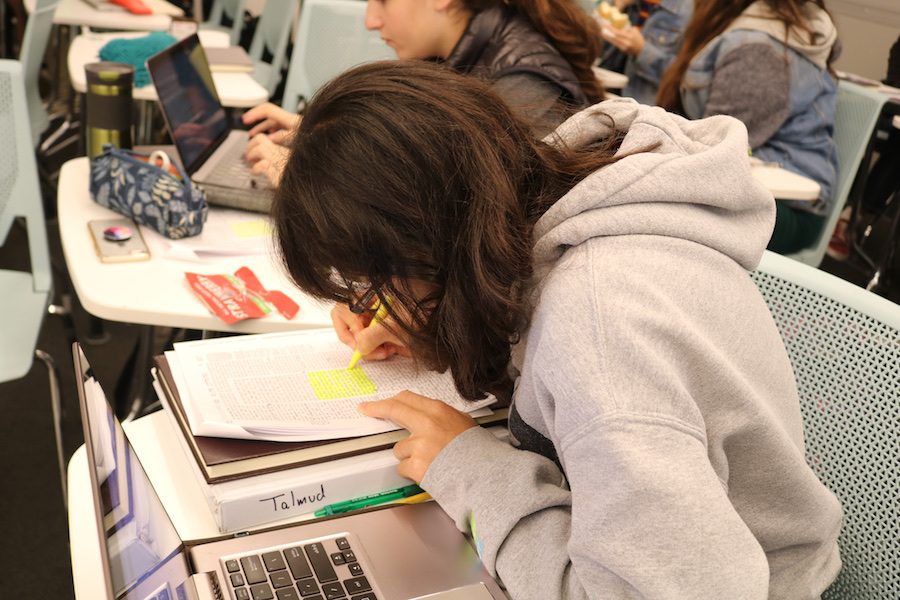

FOCUSED: Sophomore Kikuyo Shaw took notes during Rabbi David Block’s Gemara class last fall. All schools surveyed grade their Judaic Studies, classes, but some, including Shalhevet, offer additional Judaic learning with different or no incentives.

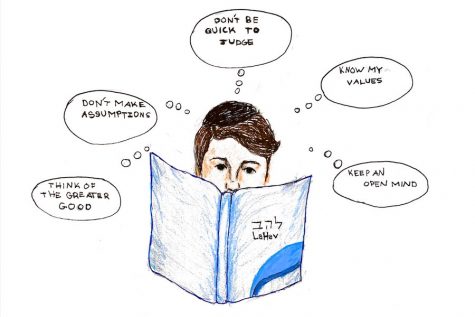

Enter a Shalhevet Judaic studies class at any given moment and you may hear the term “learning lishma” or “learning for the sake of learning,” being used. Learning for the sake of learning is a cherished value in Jewish education at Shalhevet and beyond, and an expectation of student and adult life in the Jewish world.

In an informal Boiling Point survey, teachers and students around the country agreed on its importance. But every school contacted currently grades its Judaic Studies classes — meaning that the learning is at least partly for the grade that will follow.

East Coast schools Ramaz, SAR, and Frisch and Chicago’s Ida Crown Jewish Academy all grade their Judaic classes, as do West Coast schools Milken, De Toledo, and YULA Girls and YULA Boys. Several — including Shalhevet — also offer extra opportunities for learning that are not graded, some incentivized and some not. And opinions vary on how a non-graded system would affect learning.

The Frisch School in New Jersey has an ungraded but incentivized after-school learning program, somewhat of a hybrid between grading and not grading, which can exempt students from taking their Gemara class final.

Not only is the after-school class ungraded, but Frisch junior Elana Abramovitz said that this takes some focus off of grades from their regular Gemara classes.

“If you go to 80 percent of the after-school learning programs, you can get out of taking a final,” Elana said. “Each teacher gives a certain topic for the whole year, so you sign up for the whole year, and it’s a 45-minute extra class without grades or tests.”

YULA Boys High School has various opportunities for ungraded learning, including chaburas, or learning groups, that take place after morning davening.

YULA Girls’ highest level Judaic Studies track, called Beit Midrash, is graded but does not have any graded tests or quizzes. The Beit Midrash track includes Gemara and Chumash, as well as Nakh (Nevi’im and Ketuvim, or Prophets and Writings) for juniors and Halacha (Jewish law) for seniors.

“It’s learning lishma for the most part,” YULA junior Elli Steinlauf said of the Beit Midrash program. “You kind of have to be a little bit more driven because it’s more for yourself and it’s less learning for the test.”

Shalhevet’s non-graded Judaic Studies class, the Advanced Gemara Shiur (AGS), is mandatory for students in the advanced Judaic Studies track. AGS meets either two or three times per week during the breakfast period, depending on the grade level.

In addition to AGS, Shalhevet offers Beit Midrash Chabura (BMC). These are ungraded learning sessions that meet twice a week after school and offer both Talmud and Tanakh tracks. “Daven, Breakfast, Learn,” or DBL, led by various faculty members, is also offered to students on some Sunday mornings. All are entirely voluntary.

Senior Tali Schlacht, a member of BMC Tanakh and Talmud, says the key to these programs is that the students who participate in them are self-selected and are motivated even without grades.

“There’s no tests, no homework, no anything, and we’re just like going through the Gemara, or we’ll get some snacks — totally learning lishma,” said Tali. “We’re still learning a lot, and it doesn’t take away from the learning if we don’t have grades.”

Salanter Akiba Riverdale (SAR) Academy offers multiple after-school learning opportunities with incentives similar to Frisch’s. Its after-school program, Itim, meets twice a week and exempts students from taking their Gemara final.

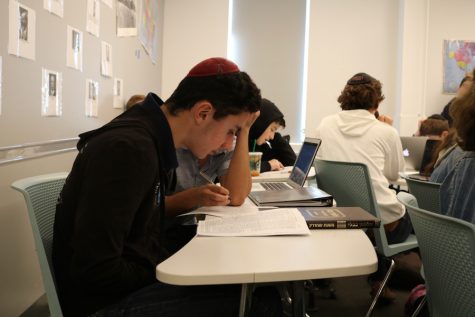

LISHMA: Sophomore Mitchell Hoenig is in Advanced Gemara Shiur, where students learn Gemara two hours a week without being graded.

“A lot of people go to learn after school, but a lot of people probably go for the incentive also,” SAR sophomore Arianne Roshwalb said.

SARl also offers Mishmar once a month, which comes with the incentive of having a grade of 100 percent averaged into students’ Gemara course grades.

“If you do Itim and Mishmar you can choose — either you don’t need to take your Gemara final or you can get a 100 averaged into your Gemara grade,” Arianne said.

Neither Ida Crown nor Ramaz in Manhattan offer non-graded Judaic Studies options. But both schools have Jewish-related clubs in which there is some learning.

Miriam Krupka, Tanakh department chair of Ramaz, said that grading Judaic Studies is important in maintaining the classes’ value.

“Kids feel pride in their grades and they feel pride in the investment that they put in a class that manifests itself on a test,” Ms. Krupka said. “So it’s a good thing that they want to do well in Judaic Studies, they want to do well on a test. It would almost be taking away that opportunity and that feeling of investment if we were to take away grades.”

However, she said that the presence of grades is not meant to extract from the importance of learning lishma.

“It’s far more important to us that they enjoy the class than that they get a good grade,” she said. “So that’s the messaging we give, even though we maintain the evaluation.”

While many students agree that grading Judaic Studies classes is important, they’re not necessarily happy about it.

Shalhevet sophomore Maya Tochner said grading detracts from her enjoyment of learning.

“I think that when Judaic Studies classes are graded, it makes it a lot harder to enjoy the classes, ” Maya said. “Instead of being excited and engaged about the material, people become just stressed out and are waiting for the next assessment.”

Arianne Roshwalb of SAR said that having tests and grades in Gemara class does not motivate people to enjoy learning.

“I have a Gemara test coming up, and for the past two weeks in Gemera, we aren’t really paying attention to what she is teaching and the values,” Arianne said. “We just keep saying, ‘Oh is this gonna be on the test, is this gonna be on the test?’”

Ida Crown junior Adam Koenig said that although it may contradict learning lishma, grades are necessary.

“If it’s not graded no one’s gonna care,” Adam said. “If it is graded, people get annoyed at that because they just wanna learn Torah. I don’t really know what the solution is.”

Shalhevet senior Daniel Ornstein, who is not in the advanced Judaic track, agreed that grades are necessary, except for AGS students.

“For AGS, it works because those are the students that chose to do it,” Daniel said. “But for the Judaic classes where everyone is obligated, you can’t not grade the students that are intrinsically motivated and grade the students that are motivated by grades. You can’t pick and choose like that, so that’s why you have to just say grades for everyone.”

But Nomi Willis, a junior in AGS, said the absence of grades sometimes causes indifference rather than increased motivation — even in motivated students.

“It’s supposed to be that you join AGS because you want to have two extra hours a week where you’re just learning Gemara to learn Gemara,” Nomi said.

“Something that I’ve noticed in my AGS class is we’re not focused on the actual material,” Nomi said. “We aren’t as serious about learning the Gemara that we’re learning in AGS as we are in our regular Advanced Talmud class, and I think that that’s really interesting because when we have no extrinsic motivation, or what it’s supposed to be, we’re really not that serious.”

Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Ari Schwarzberg agreed that students are less serious about learning without the motivation of the grade in AGS.

“Without the grade, you don’t have students going home at night and reviewing,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said. “They feel like,‘It’s no big deal if I don’t follow along or don’t feel the same commitment.’”

This concern seems to be a reason that many students and teachers believe that classes, regardless of their religious significance, must be traditionally graded.

“In theory, it would be nice if we were all just learning for the sake of learning,” Frisch’s Elana Abramovitz said. “But in a school, if classes were never tested it would just be a joke, and that’s like half our day wasted.”

But that does not mean the effort to promote learning lishma should cease even within the parameters of having grades.

Six years ago, in order to ensure that students weren’t enrolling in the Advanced Judaic track to take advantage of grading benefits, Shalhevet administration stopped giving the classes the GPA boost that all other honor and Shalhevet Advanced Studies (SAS) classes receive.

Shalhevet is alone in this policy. Ida Crown, Ramaz, Frisch, and both YULA boys and girls provide GPA boosts for their honors Judaic studies.

“We didn’t want the students to go into the advanced Judaic program in order to boost their chances of getting into X university…” former principal Dr. Noam Weissman said in an interview earlier this year. “We wanted the students to be enjoying the advanced program because they wanted to enjoy themselves, regardless of the GPA boost.”

But that strikes students as unfair. Junior Adam Ritz, a member of the advanced Judaic track, thinks that these classes should receive a GPA boost to reward students’ hard work.

“If [advanced] Judaic classes are to be graded, then they should go towards our GPA because it’s a numerical representation of our achievements,” said Adam, “and I feel like if we obtain a certain achievement and we conquer a class, then it should be going to our overall GPA and grade.”

Whether Judaic classes are graded or not, all who were interviewed agreed that learning — lishma or not — was important.

Shalhevet Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Abraham Lieberman, who was previously Head of School at Yula Girls high school, said that learning Torah — both shebek’tav, the written Torah, and sheba’alpeh, the oral Torah — is a crucial aspect of Jewish life.

“All of education is important, we should know everything,” Rabbi Lieberman said. “General studies, science, mathematics, are surely super important. But at the end of the day, as much as those things are important, as Jews, and to live our lives as Jews, we need to know our heritage, we need to know our history, we need to know our text, and Torah — both she’bectav and she’baalpeh.”

No one disagreed.

“It is important to learn Torah and study Judaic subjects because it connects us with our past,” YULA sophomore Gavi Gershov said. “We learn about our heritage which allows us to live better lives.”

Staff columnist Eva Suissa and Staff Writer Molly Litvak contributed to this story.

Lucy Fried was co-editor-in-chief during the 2018-19 school year and went on to study at the Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. She is now a junior at UC Berkeley.