Scholar says ‘kol isha’ rules should never have existed

OPEN: Dr. Amit served coffee to students in an open sided tent on the rooftop turf during his two-week residency in February.

Talmud professor Dr. Aharon Amit was not allowed to attend his daughter’s third birthday party. Worried that female teachers would sing “Happy Birthday”, the Haredi ethos of his community barred his presence, citing the halachic principle known as kol b’isha erva.

Translating to “a woman’s voice is nakedness,” the phrase in Bavli Kiddushin 70a and Berakhot 24a has traditionally been interpreted to mean that women should not sing in a public domain, and that men are forbidden from hearing them. Dr. Amit shared the story with the upperclassmen’s AGS class as part of a two week scholar-in-residence visit Feb. 8-19.

Shalhevet takes a more liberal approach to kol isha, permitting female students to sing in a group or even as soloists – and letting male students hear them – as long as they are dressed modestly and the lyrics are not lewd.

But Dr. Amit, who teaches Talmud at Bar Ilan University in Ramat-Gan, gave students a completely different way of viewing kol isha, one that went a step further.

After decades of Talmud studies, Dr. Amit believes kol isha was originally not intended to become a law.

“I’m against restraining women’s participation in singing — they should be able to do any type of singing that they want,” Dr. Amit said in his sides-open tent on the rooftop turf, where he served coffee to students throughout his stay.

“Usually when people talk about kol isha, they don’t talk about it from a position of knowledge,” he said. “It’s an emotional topic.”

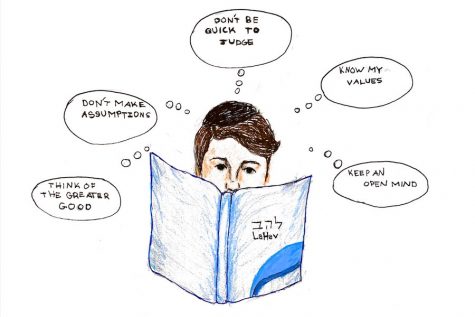

There are three main premises to the professor’s claim, which he shared also with some of the ninth grade Music Appreciation classes. First, he discovered that the earliest manuscripts of the Bavli Kiddushin 70a do not contain any reference to kol isha at all, but rather the phrase was inserted there later on by authorities who knew of the statement of Samuel in Bavli Berakhot 24a.

Second, the rabbinic figure this statement is attributed to, Samuel, seems to have made the comment in a narrative, non-halachic context, Dr. Amit said. The rabbis of the Talmud – all male, he noted – were discussing what they found beautiful in a woman, and each named another female attribute. The word erva thus might not have meant “nakedness” in that context, but rather beautiful or tempting, and was used rhetorically to emphasize the extent of the temptation.

“The kol isha statement by Shmuel was not intended as a halachic obligation, and it was not said in a halachic context,” Dr. Amit said. “It was said in hyperbole about what is tempting about a woman. In the context of that discussion, some of the things mentioned were a woman’s voice, hair, thigh. Therefore today, the voice of women need not be prohibited either in speech or song.”

Lastly, once Samuel’s statement did begin to be incorporated into law, it was thought to mean that anything about a woman’s voice was improper for a man to hear during kriat shema – even her speaking voice. Later, that was beginning to be impractical and forbidding singing was conceived as a more lenient interpretation of Samuel’s words.

Still, the Haredi world in which Dr. Amit was living when his daughter was three saw a wide prohibition. Today, many Orthodox communities extend it to girls singing in concerts, national anthems, and apparently even toddler birthday parties. There are religious communities where women don’t even sing at bentching, the grace after meals which on Shabbat and chagim is usually sung by all at the table.

Shalhevet disagrees. As adopted by Head of School Rabbi Ari Segal in 2012, Shalhevet’s policy allows women to sing provided it is not in a provocative fashion. Before Rabbi Segal arrived, girls could sing in a choir but could not be soloists.

Citing a teshuva written by Rav David Bigman, the Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshivat Ma’ale Gilboa in Israel. Rabbi Segal changed the policy to allow female solos in 2012, making Shalhevet the first Orthodox school in Los Angeles to do so.

“I went through the teshuvot of Rav Bigman … and the primary sources, and feel comfortable with the notion that kol isha, applies [only] to solo singing of a sensual nature,” Rabbi Segal said in 2012. “If a student is dressed properly, the song is about a modest or even holy concept, and she is not singing in a way that is intended as erotic – then I believe yeish al mi lismoch – there is halachic support for this.”

But for Dr. Amit, the law itself is an entire misinterpretation of the Talmud. To spread awareness about his perspective, he intends to publish two articles on his discoveries.

One will touch on the historicity of the statement. Dr. Amit showed the AGS class three versions of the Gemara in Kiddushin 70a. The earliest manuscript, currently presiding in the Vatican Library, does not contain any reference to kol isha,

“Kol Isha does not appear in the authentic version of Bavli Kiddushin,” he said. “I showed through the manuscripts that in Bavli Kiddushin it was added much later, after the Talmud was redacted, probably in the later part of the Gaonic period.”

His second article will touch on the context of Samuel’s original statement, which could marginalize its authority by pointing out that the rabbis were discussing what they found tempting or attractive in a woman.

If Shmuel’s statement was intended to be a law, he was referring to a woman’s voice in general. Prohibiting singing, Professor Amit said, only came up in the 12th century, thanks to Eliezer ben Shmuel of Metz, who understood Samuel’s statement only to prohibit hearing a woman sing during keriat shema or other ritual activities.

“What Eliezer ben Shmuel of Metz meant to do was make what he understood to have a certain halachic implication be easier to live by,” Professor Amit said. “If you can’t ever hear a woman’s voice that would be difficult, but restricting it to women singing would make you able to do it.”

In addition to the halachic problems he’s identified, Prof. Amit is concerned about negative consequences of preventing women from singing.

“Every human voice is beautiful and holy,” Dr. Amit said. “The danger of making kol isha [a law] is making a girl look at her voice as problematic. I want every person to see their voice as something they love and something they could share in the public domain. I really don’t want to see a prohibition of kol isha in public sphere.”

But despite his textual and historical evidence, changing Orthodoxy’s overall policy seems unlikely. Different bodies of rabbis decide on today’s halachic issues, and some view Samuel’s statement as a clear law.

“From their perspective, they see this as a halachic absolute,” Dr. Amit said. “They took what [Eliezer ben Shmuel of Metz] said as the singing voice being the interpretation of Samuel, even though they usually don’t talk about that being a later interpretation but [rather]as the pshat – the plain meaning of what Samuel meant.”

Brought up in a non-observant family, Dr. Amit was introduced to Talmud in his early 20s and decided to pursue it through yeshiva in Israel after college. After three-and-a-half years in yeshiva, he earned a masters and doctorate in Talmud at Bar Ilan University, with a focus on analyzing manuscripts. For the past two decades, he has taught various classes at Bar Ilan.

“I felt what he said had backing and he proved his points very well,” said junior Isaac Goor. “I agreed with it, but he’s disregarding the mesorah [tradition] a bit, but I do agree with what he had to say.”

For the sophomore class, he taught a lesson on the controversial blessing of shelo asani isha, where men seemingly praise God for not being made women. Prof. Amit’s interpretation, based on the scribal tradition of Psalm 100:3 and an article by Ishai Hasida, interprets the word lo not as “do not” but as “to Him,” thereby making the blessing a positive praise of thanks for making the reciter “married” to God. This way the blessing can be recited by both men and woman and expresses gratitude for an intimate connection to God, rather than expressing thanks for not being a woman.

“I thought he put an interesting spin on it, and changing that bracha from a negative light to a positive light,” said sophomore Benny Zaghi.

Overall, students said Dr. Amit brought a lot of Talmud knowledge and passion to the school – along with good coffee, which he prepared for students every day in his tent on the roof.

“He brought extensive Talmudic knowledge to the school, and he brought a different perspective to how we discover Halacha and a different approach to learning,” said sophomore Jacob Perelman. “So I very much enjoyed his presence at Shalhevet I also liked that he made us coffee.”

After serving as staff writer, Features Editor, and Outside News Editor over the previous three years, Eric Bazak served as Editor-in-Chief for the 2015-16 school year. He is currently a freshman at UCLA.

Eric won numerous awards for his work on the Boiling Point.

CSPA 2015 Gold Circle Certificate of Merit in News Writing (print)

CSPA 2015 AGold Circle Certificate of Merit in In-depth/Feature Story (print)

Quill & Scroll 2016 National Award in Profile Writing

Quill & Scroll 2015 National Award in News Writing

Jewish Scholastic Press Association, 2014 2nd Prize in News & Feature Writing

david • Apr 27, 2016 at 11:00 pm

Does Dr. Amit acknowledge that the source of the prohibition is not the passage (from the Vatican) in Kiddushin 70, but rather the UNCONTESTED statement in Berachot 24? . There, a woman’s sexually exciting attributes, such as viewing of privates, hair, or legs are compared by Shmuel to the hearing of her voice. All are desirable within a marriage, and immodest elsewhere.

Michoel • Apr 27, 2016 at 5:35 am

Women may sing for women in EVERY Orthodox circle. How is that curtailing the female voice? It isn’t. Sing all you want, just make sure it is a female audience. Simple. Why is there a strong need to sing in front of men? Why do men have a strong need to listen to women? It makes no sense to me.

The real issue is that if women are being taught that their voice is “problematic,” then that means that they are being taught that their other body parts are “problematic,” and THAT really is messed up. The solution is not to allow singing for women in the presence of men, but to reorient their understanding of Tznius in general. What is beautiful about concealing the “attractive” parts of a woman? How is this spiritually inspiring? Why is it so important? THESE is the real questions that need to be examined, not teaching women that they are problematic and finding ways to be lax in halacha.

Linda • Apr 28, 2016 at 2:19 pm

@Michoel I am guessing that you don’t have a clue about how segregating women with Kol Isha makes them feel. That’s OK. Let’s get past that. What if you are a women with a voice as phenomenal as Lipa Schmeltzer, but you cannot make as good of a parnasa from this gift from Hashem because male Rabbis mistakenly feel that your voice is too tempting for 50% of the population to hear? Why the double standard? Are women so asexusal that they are not aroused by Lipa’s voice? Why can’t men control their sexual urges? Why do women have to confine and restrict themselves because men have no control? Why won’t Haredi men sit next to women on an airplane? To me this reeks of misogyny and an attempt to control women. Why the need to constantly raise the bar, interpreting Halacha ever more stringently as the years go on?

I’m guessing that your life is so constrained by your fear of hearing a woman’s singing voice that you’ve never seen a Broadway play, gone to the opera or listened to a phenomenal rock or blues singer. What a shame. These are the questions that need to be asked.

Maurice • Apr 26, 2016 at 3:48 pm

Curtailing the listening of the inspirational force of female voice in devotional song is in my view chilul Hasham. Song magnifies music and devotional music is an expression of the glory of Hashem. The female voice with its sense of mystery furthermore sanctifies this glory. Vayitkadal Vayitkadash

david • Apr 27, 2016 at 8:42 pm

Of course women can have beautiful, inspiring voices…since antiquity, the Song of the Sirens has been a cross-cultural symbol for…distraction.

carole Weinstein • Apr 26, 2016 at 3:45 pm

Please refer to earlier questions.

carole Weinstein • Apr 26, 2016 at 3:44 pm

When will he be speaking in NY, if at all, and where?

carole Weinstein • Apr 26, 2016 at 3:43 pm

where does Prof. Amit stand on the great religious divide today?

Stephen Games • Apr 26, 2016 at 2:30 pm

I didn’t know that the archives of the Vatican were now open to study. Is the catalogue available online?

Zvi Septimus • Apr 27, 2016 at 10:42 am

the manuscript for this page can be found here

http://jnul.huji.ac.il/dl/talmud/bavly/showbav1.asp?mishnanum=1&pereknum=072&masecet=30&mnusriptnum=358&p=1&masecetindex=19&perekindex=69&numamud=1&manuscriptindex=2&k=