Why you’re wrong about feminism

February 14, 2014

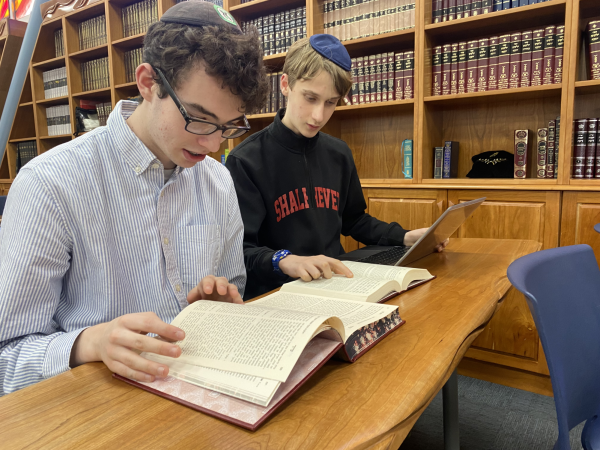

I recently asked a few of the Girls Learn International club members—both girls and boys—whether or not they consider themselves feminists. Half of them didn’t, though GLI is a club that educates American youth on the gender gap in education around the world, and advocates for girls to have the same educational opportunities as boys in places where equality is lacking.

The discrepancy didn’t take me by surprise, but I was disappointed—there are people who are working toward gender equality but who don’t call themselves feminists.

If you’ve listened to Beyoncé’s new song “Flawless,” you’ve heard a sample of Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TEDx Talk called “We Should All Be Feminists,” in which she defines a feminist as “a person who believes in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes.” The Oxford Dictionary and Merriam-Webster concur.

And in fact, though I wholeheartedly agree with the definitional concept of the word “feminism,” it hasn’t been easy for me to embrace it as a label even for myself.

Often it feels like in order to call myself a feminist, I need to conform to a standard that goes far beyond that definition, and that I’m not a “true feminist” if I don’t.

For example, I’m not about to make a feminist critique on everything I see. Clueless, Legally Blonde, and Mean Girls are three of my favorite movies (the trifecta of chick flicks, I know). But while some may roll their eyes and argue that the films’ protagonists perpetuate stereotypes of women as manipulative, ditzy, and shallow — and there certainly are times when they are — I prefer to appreciate the fact that the leads are ambitious women who set goals and actually achieve them, whether it’s linking two teachers romantically or graduating from Harvard Law.

For me, being a feminist at 18 means advocating for equality, but also religiously reading betcheslovethis.com. It’s a lifestyle and pop culture blog written by anonymous women who call themselves “The Betches.” My older sister considers it misogynistic, though I prefer sarcastic and satirical. As they said in their blog post last Oct. 25, the Betches emphasize the importance of “choosing a (slutty) Halloween costume” and marrying Investment Bankers—material that could certainly be considered “unfeminist.”

My own feminism perhaps is not what would be called politically correct. But I’d like to I think I can appreciate their humor anyway — just as we Jews can sometimes appreciate a good Jewish joke, like when Jon Stewart makes fun of Jews for having a knack for complaining. (“Black people have blues music, while Jews complain – we just haven’t thought about putting it to music,” Stewart has said.)

Some might say there’s a conflict here, but I don’t think so, because I still believe in the core tenets of feminism. The reality is, being a feminist just means you want girls and women to have equal opportunities, and the ability to make their own decisions. It doesn’t mean I have to think a certain way about everything I see or hear, or that I should judge someone for wanting to dress provocatively or marry rich.

Still, if it hasn’t been easy for me to label myself a feminist, it’s not hard to understand why it would be difficult for other students, and even GLI members. Some people think it’s a label exclusively for women, and not masculine for a male to use for himself. Others may think that women who call themselves feminists don’t like men, or don’t want men involved in their lives.

The word also clearly has some historical baggage associated with early feminism of the 1960s, when what was then known as the women’s liberation movement was still fairly novel and led by radical pioneers.

In 2014, the way for feminism to transcend such stigmatized conceptions is for people who don’t hold those radical beliefs to embrace the word nonetheless. An active feminism that pursues social, political and economic equality can be a movement that is not only effective but gradually changes the connotation of the word — or perhaps restores it to what Oxford and Webster said it was all along.

Like any movement — liberalism, socialism and Zionism come to mind — feminism has adherents who disagree on lots of things. But the important thing is what we achieve together, and naming ourselves what we are will help make that happen. If more people call themselves feminists, perhaps one day we’ll accomplish our goals. It sounds cheesy, but there really is strength in numbers.

There is no archetype you need to fit in order to assume the label—and if more people do take it on, it will diffuse the stereotypes that weigh feminism down, thus reinforcing the notion that really everyone is a feminist, which in turn will propel the movement further. If almost everyone agrees that men and women should be equal, then there’s no reason why they shouldn’t be, in practice!

That’s why I don’t want to be the only feminist I know. And by its actual definition, I don’t think I am. It’s time for the rest of the world’s feminists — and you probably are one yourself — to embrace the term and reclaim the movement. Hopefully the next time I ask, Shalhevet’s GLI club members won’t hesitate to call themselves feminists—and neither will you.