REVIEW: In ‘Ladybird,’ a teenager finds clarity in an old genre made new

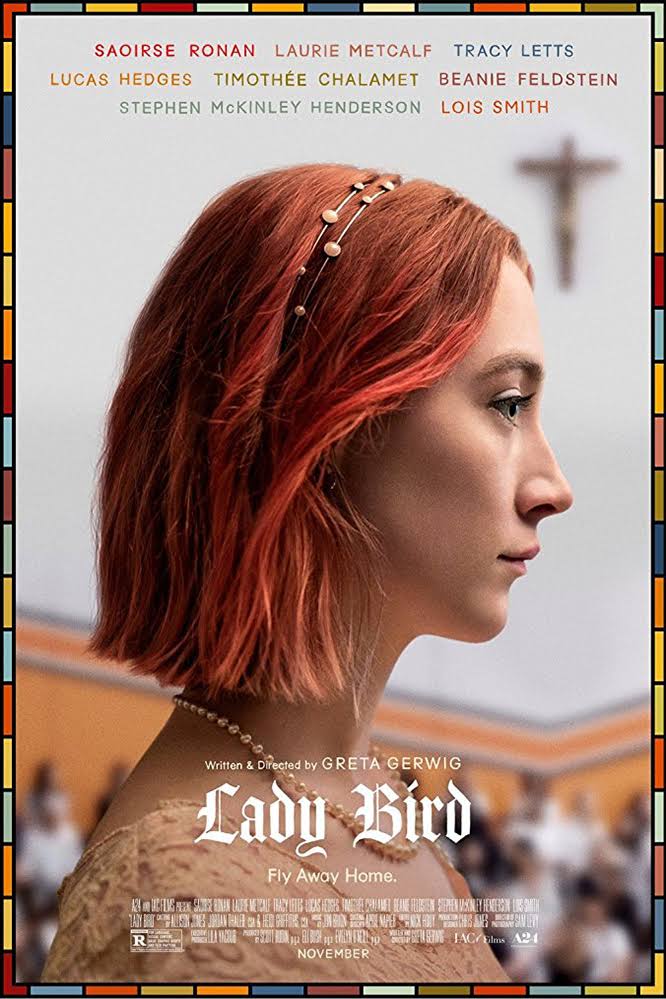

imdb.com

imdb.com

The classic coming-of-age story, known as abildungsroman, has been written and rewritten throughout history, its name coined in the late 18th century and the form itself documented since Homer’s Odyssey, 1,000 years before that.

Ladybird is a classic bildungsroman with a modern twist. Set in 2002 and directed and written by Greta Gerwig, it establishes its coming-of-age identity right in the title. The character known as “Ladybird” is asked early on whether that’s her given name, and she responds: “Yes, it was given to me — by me.” She is a spunky senior in high school who wants to leave her self-contained neighborhood of Sacramento for bigger and better things in New York, away from her tumultuous relationship with her mother, away from her religious high school, and far from her house “on the wrong side of the tracks.”

And while that plot line sounds as classically quirky as many a young adult novel, that is kind of the point. Like a lot of teenagers, Ladybird tries a little bit too hard to be her own person, crossing the line in moments that show she is forgetting to listen to herself in her quest to be honest and unique. But at the end of the day Ladybird is truly a woman who pulls no punches when it comes to what she wants and ultimately who she wants to be.

Because it is so classic in this way, and because it has received so much hype — it’s Oscar-nominated for Best Picture and winner of 15 2018 Golden Globe Awards, including Best Motion Picture, Musical or Comedy — it is normal to assume the hype stems partly from a lack of exposure to independent films in the mainstream population. And that is is definitely part of the reason it is so well-loved.

But there is so much more. First of all, Ms. Gerwig conveys the modern understanding of human duality. Ladybird is not always the hero, and those who hurt her are not entirely bad. The boy who lies to her father is coping with his father’s terminal illness, and the disapproving nun has a wicked sense of humor.

Ladybird herself has faintly pock-marked skin, a skirt that hangs a little too long for her to be naturally popular, and a tendency to say the first thing that comes to her mind — but with fear of ridicule by her peers. All this makes her believable. She is also pretty but the actress who plays her, Saoirse Ronan, is not made up to look Hollywood gorgeous — something that is consistent throughout the cast. The characters all look (shocker!) like real teenagers.

Also authentic are her obsession with filling out the FAFSA, a financial aid document for college, and her experience in the college counselor’s office being told to be “realistic” about where she should apply (even as she was being realistic). The difficulty of applying to college, especially with financial concerns, is very real for Ladybird, and not hidden in the movie. Her reckless ambition, trepidation and uncertainty about what she wants pay homage to teens’ ability to be completely stupid without an ounce of apathy.

Then there’s her relationship with her mother, played by Oscar-nominated Laurie Metcalf. When this similarly multi-dimensional mother bitterly cites the expense of having raised her, Ladybird replies, “You give me a number for how much it cost to raise me, and I’m going to get older and make a lot of money and write you a check for what I owe you so that I never have to speak to you again.”

It is not that she believes her parents only think of her as a person who sucks up their resources but that she doesn’t know how to feel more grateful than she does and yet is still a person who wants to be taken care of. She is no longer a child who can be told what to do, but she is far from being alright on her own. This is the truth of becoming an adult and navigating the new type of relationship that forms between child and parent.

At the end of the day, Ladybird reaches an important conclusion about parents: you might not get their approval, but you will always have their love.

This acknowledgment and growth is a key part of any bildungsroman. Trying to answer her questions about life, she eventually accepts and cherishes the family and town she had been desperate to leave.

Ladybird the movie, unlike the character and unlike many bad teen flicks, is not trying too hard to be unique, or to reinvent the coming-of-age story, or to create new movie techniques. The movie is just too honest for that.

But honesty is something that hits everyone hard because it is something we rarely are able to see laid out in front of us so clearly. Extremely dramatic and emotion-wrought scenes will end and there is no break between the ending and her smiling in a new scene. It depicts the way that things that feel earth-shattering one second become distant memories the next and the challenges that seem impossible to overcome become happy days with new confrontations.

Ladybird is also laugh-out-loud funny, with scenes like Ladybird and her best friend eating the church school’s communion crackers and talking about masturbation, and a football coach directing a school play like it is a football game.

It depicts the life of an honest and flawed teenager whose struggle is neither minimized nor revered. Watch this movie to see why it is teenagers act in ways that are baffling but not necessarily ill-intentioned.

Aidel Townsley has written for Boiling Point since she transferred to Shalhevet three years ago. Most proud of her advice pieces for the Boiling Point, she is now Opinion editor. Her other interests include music, psychology and biology.