On a sunny Friday afternoon, sophomore Yarden Harel was standing on the Sport Court holding a chicken upside-down, moving it in circles over his head, and reading what seemed to be an incantation.

“Zeh chalifati, zeh tamarati, zeh kaparati.” Yarden said. “This is my exchange, this is my substitute, this is my expiation…”

No, it wasn’t a lesson on kashrut or something else having to do with animals. Rather it was the famous ritual of kaparot – literally, atonements — a tradition that likely began with the Jews of ancient Babylonia and which is still performed today during the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

Kaparot takes note of the idea that if God were to exact justice, one would not live for another year – even with the forgiveness of Yom Kippur – because of all the sins that he or she has committed. A chicken is waved above the head three times so a person can symbolically “transfer” his or her sins to it. Later, the chicken is killed, presumably instead of the person whose sins would otherwise be fatal.

Various authorities from Ramban to Rav Yosef Caro have called the practice “foolish” and even pagan, and it has never been a formal part of Judaism. But it has persisted in some circles nevertheless, and on Oct. 7, Erev Yom Kippur, it had its debut at Shalhevet.

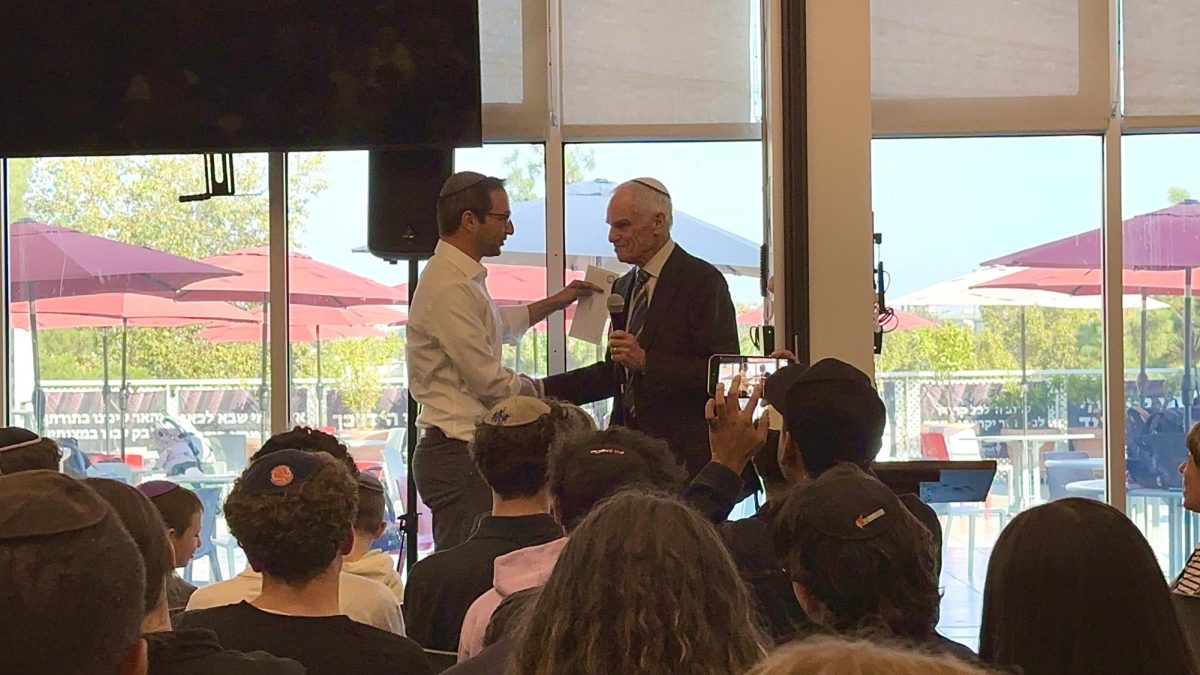

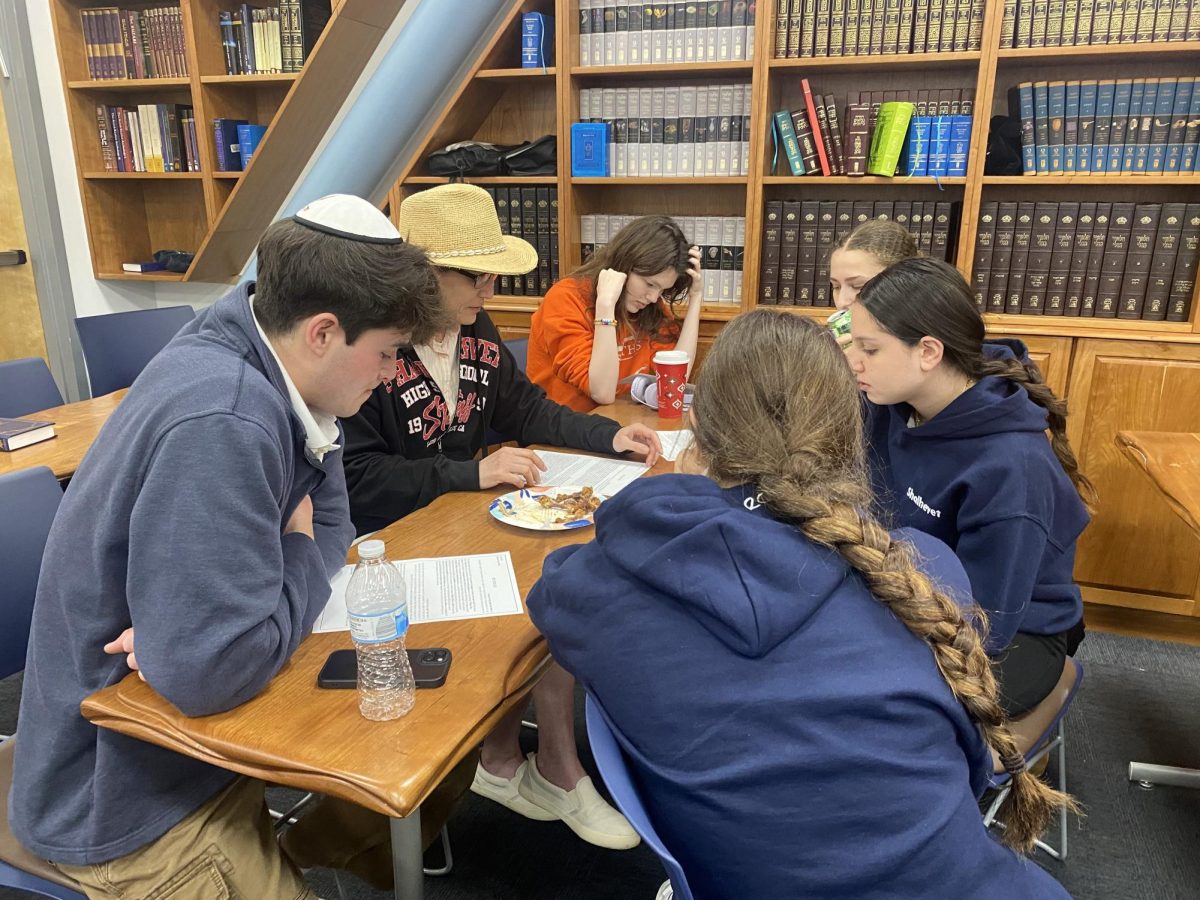

After an announcement on the PA system at the beginning of lunch, students, faculty and staff congregated on the red and black plastic-tiled court, normally the site of pick-up basketball games, eating or homework at that time of day. With just hours to go before Yom Kippur began, some took hold of the live chicken themselves; others, mostly female, asked someone to hold it for them.

While the hen rotated above them, they nervously poked their heads to the side to read and recite the prayer. Judaic Studies Principal Rabbi Ari Leubitz, who was quietly standing alongside and holding a copy of the text, whispered words of encouragement.

As each student finished, he or she would gently hand the chicken to the next person in line, and embrace a look of either shock or fulfillment while walking away.

“I feel pure,” said freshman Adam Rokah as he headed back inside. “I feel spiritually different now.”

For Adam, along with most of the school, this was not only a first experience performing kaparot, but also the first time they had ever seen it.

“I was so confused and surprised that the school did this,” said freshman Rebecca Elspas, who just watched. “It was shocking to see someone hold a chicken around his head upside down. I knew that they do this, but it was so weird and different seeing it in person.”

As some observers snickered, sharing their opinions on whether or not the ritual was moral, others strolled around the area searching for someone who would agree with them, whatever their view.

“I have been doing this my whole life, and I think it’s wonderful because first we have the opportunity to symbolically transfer our sins, and even after that, the chicken goes to charity and makes a family happy,” said junior Naomi Abehsera.

In the midst of the commotion, it was suggested the chicken be given a name. Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Ari Schwartzberg ventured “Sin.”

For its part, the chicken – a snow-white hen with bright eyes and a red bill – seemed very calm and did not flap its wings or otherwise resist.

About half the students who performed kaparot wore disposable latex gloves, while the rest were barehanded. By the time lunch was over, the bathrooms were filled with students waiting for a sink, staring at their hands.

A total of 12 boys and nine girls had successfully performed kaparot, while about 20 more showed up only to catch a glimpse of the event. Curious or not, many said the ritual was too far out of their comfort zone.

“It’s gross, I don’t know why anyone would want to hold a chicken,” said freshman Shana Chriki, who watched but did not participate. “I’m just not doing it because it’s too disgusting.”

Nowadays, many Jews consider kaparot to be outdated. In fact, since the 16th century, money has as an alternative. Instead of holding a live bird overhead head and then killing it, today more Jews say the prayer and wave dollar bills.

“I think money serves the purpose just as fine, and I don’t feel comfortable using a chicken,” said senior Josh Meisel, who performs kaparot using dollars every year and didn’t even watch on the Sport Court that day.

The idea for the Erev Yom Kippur event came from Director of Development Aaron Keigher, who saw chickens for sale at Congregation Ohel Moshe on his way to school and bought one to share with students and staff. “It was kind of a spur-of-the-moment decision,” Mr. Keigher said. “After I saw the sign driving to school, I just said why not. And since we have the opportunity and the place, we thought it was a nice idea. So I bought the chicken for $26 and brought it to school.”

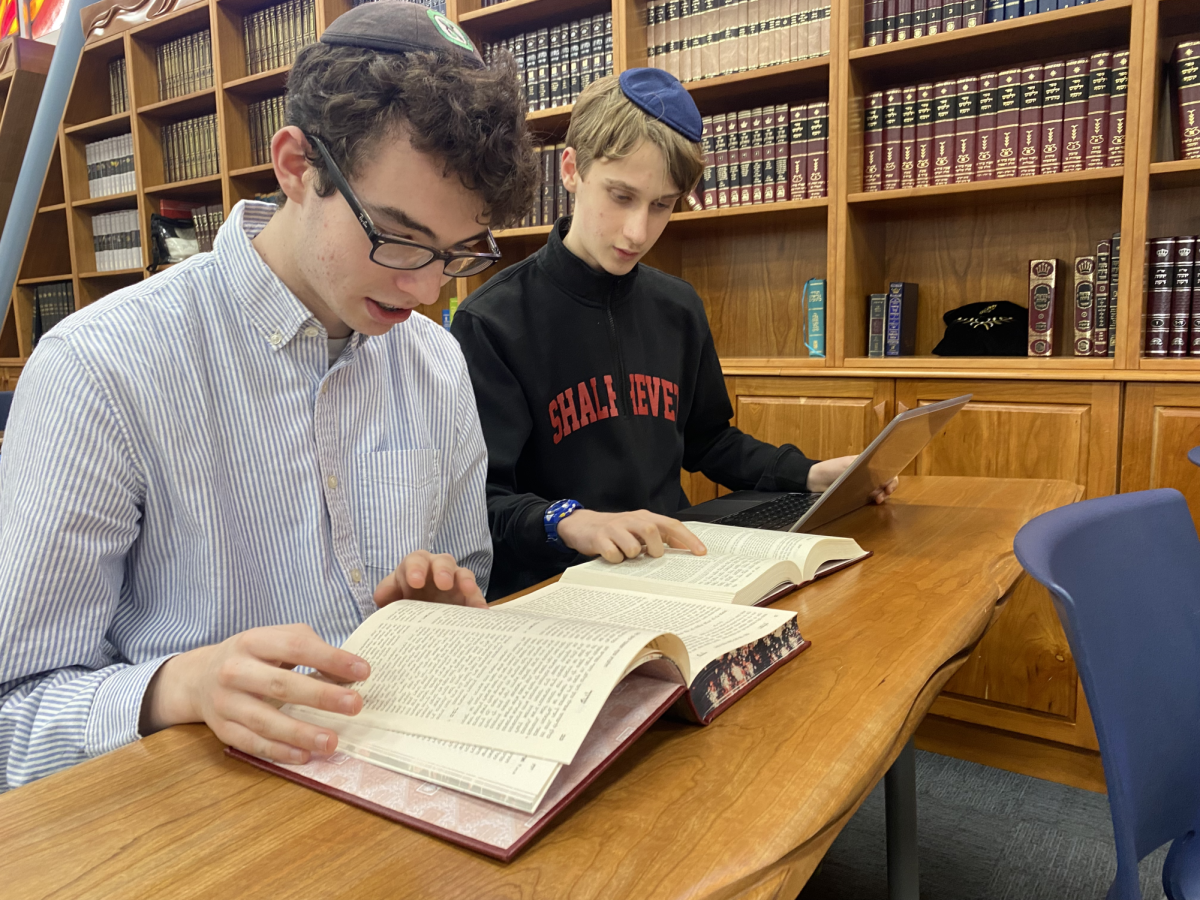

Mr. Yossie Frankel, ninth-grade physics teacher and Director of Technology, was asked by Mr. Keigher to assist.

“I don’t mind handling animals, since I’ve been trained to schect” — that is, to slaughter according to the rules of kashrut — Mr. Frankel said later. “But I wanted to make sure that everyone who holds the chicken understands that this is a living creature, and this is no joke.”

Mr. Frankel opened the event with a six-minute introduction to the practice. The schechting, or killing, he said, would not be done at school – only the blessing, along with the waving of the chicken over one’s head three times, as per tradition. The chicken would then be taken back to Ohel Moshe, where it was purchased, to be schechted there.

Mr. Keigher said there was no reason to kill it at school, since Mr. Frankel is not in practice and school had neither the knife nor the facilities.

Mr. Frankel said kaparot was “useless unless you’re in the right mind space,” and several students eagerly scrambled into a line.

No one could expect that there would be more to come with this event. But as the second student to try it grabbed hold of the upside-down chicken — almost dropping it — Mr. Frankel reached into its brown cardboard box and pulled out an egg.

“No, I’m completely serious,” Mr. Keigher said to Head of School, Rabbi Ari Segal, who seemed not to believe his eyes. He held up the egg – proving that perhaps the chicken wasn’t as uncomfortable or surprised about the ritual as many students were.

“We’ve got Sin Junior in there,” said Rabbi Schwartzberg.

Asked why kaparot had never been done at Shalhevet before, Judaic Studies Principal Rabbi Ari Leubitz said it was partly because Erev Yom Kippur hadn’t fallen on a school night. He also said that since it wasn’t a commandment, it hadn’t been a priority for the school.

“This is optional,” Rabbi Leubitz told The Boiling Point. He himself did not take part in event, but observed.

“I only participate in minhagim that are meaningful to me, and this was not for me,” Rabbi Leubitz said.

“For some people, however, having a live animal is more meaningful,” he added. “I’m too removed from dealing with live animals, so I’d be focused on the animal and not the kaparot.”

VIDEO: Kaparot on the Sport Court Oct. 7 11/3/2011

Related: Two Boiling Points of View – Kaparot: Cruel and un-Jewish 11/7/2011

Related: Two Boiling Points of View – Kaparot: A way to feel guilt 11/7/2011