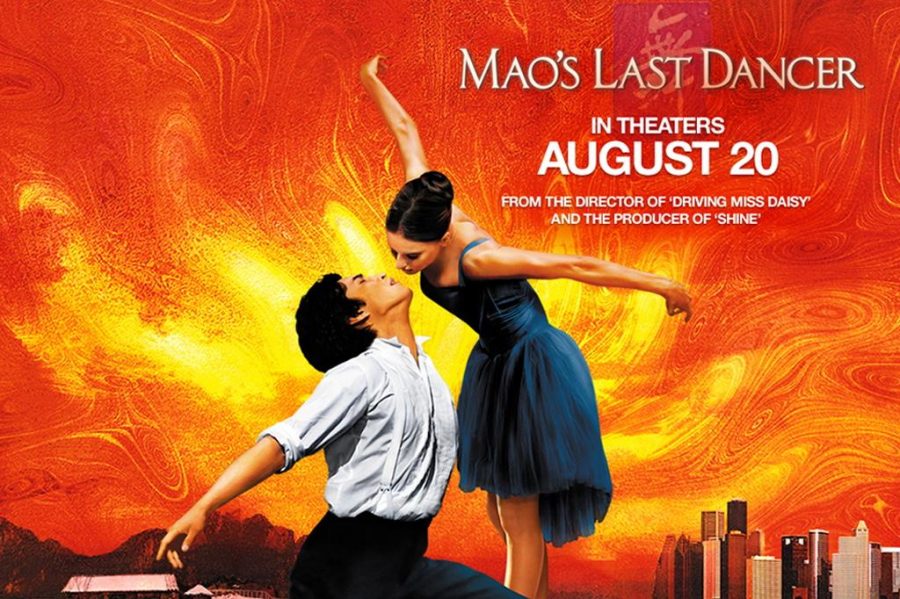

Mao’s Last Dancer is a biopic of Li Cunxin, the Chinese dancer who boldly defected to America in 1979. Directed by Bruce Beresford, the film was just what I expected and resonated emotionally with me as a child and grandchild of immigrants. Plucked from his family’s impoverished provincial home by Communist officials as part of Mao Zedung’s Cultural Revolution, Li Cunxin is given the chance to honor his family by becoming a ballet dancer with the Beijing Dance Academy; then, In 1979 as part of a cultural exchange program, Li gets the chance to study with Houston Ballet.

Immensely talented, Li is immediately embraced by the Houston Ballet’s Artistic director, Ben Stevenson, and seizes the opportunity to remain in the United States. The reason assumed is that America offers him the unrestrained freedom he needs to become a world-class artist. While Berenson leaves largely unexplored the various implications this has for Li’s family and his own psyche, nevertheless through beautiful dance sequences and heavy-hitting melodrama, Mao’s Last Dancer tells the story of a young immigrant who risked it all for a chance to make it in America.

Beresford does a superb job capturing the viewpoint of an immigrant escaping Communist oppression. Never contrived, the film is filled with vignettes that will be familiar to anyone who is or knows someone who has immigrated to the United States, especially from a communist country. When Ben takes him shopping, Li is dumbfounded that Stevenson would spend $500 in a single day while his family back home earns just $50 a year. My grandparents, who are immigrants from communist Russia, to this day seem just as infatuated with $50 dollars as Li is. For the past 15 Thanksgivings at our house, my grandfather has reminded us they had only $50 to their names when they arrived from Russia in 1974. In another scene, Li literally looks over his shoulder as he shushes his coworker who has just admitted to hating then-President Reagan. To this day my grandmother refuses to call our golden retriever by his name, Rumsfeld, because she fears retaliation from the Bush administration. I guess that once you live under a repressive regime, you just can’t shake the fear.

However, I wanted a better reason why Li chose to defect the U.S., and without it, many may find it hard to believe that repressive regimes really did employ scare tactics to keep people in line; in other words, since Li doesn’t seem to have any trouble dealing with them, maybe the threats weren’t real. When Li begins expressing hopes to simply extend his stay with the Houston Ballet, Chinese officials tell him in no uncertain terms that his family will be shamed. So why does Li do it? The reasons the film offers are glitz, and love with American girlfriend. But why doesn’t it at least examine the importance of self-determination? The looming problem with this film is that it does not grapple with the ethereal and hard-to-define idea of liberty, a value which in a story like this one surely plays an important role.

Though Chi Chao’s acting felt stilted, he more than made up for it with his exquisite dancing. Bruce Greenwood’s understated and nuanced portrayal of Ben made it impossible to recognize him as the boss in last summer’s Dinner for Shmucks. Also notable was Kyle MacLachlan as Charles Foster, the immigration attorney key in securing Li’s decision to stay in the U.S. But outside of the dance sequences, excepting Greenwood’s and MacLachlan’s performances, the movie is weak. We are never told what propels Li to just break with communism and choose capitalism. Unfortunately, Beresford gives us only the duh possibility, “Well who wouldn’t want to live in America, with it forest of skyscrapers and pretty red-haired girlfriends?”

In addition to all the ballet on the screen, I enjoyed watching the audience of mostly senior citizens adjust their hearing aids as they realized that the film had no subtitles and was actually not a foreign film – some were none to pleased by this and actually walked out. I also learned some ballet terminology: for example, while the leading female dancer is a ballerina the leading male dancer is called a danseur, and not Big Ballerino.

But most of all, Mao’s Last Dancer is something I could never get tired of: a beautiful translation of an immigrant’s rise to success in the United States of America. The American dream lives on.