Pesach is behind us. Why was it the peak of the year?

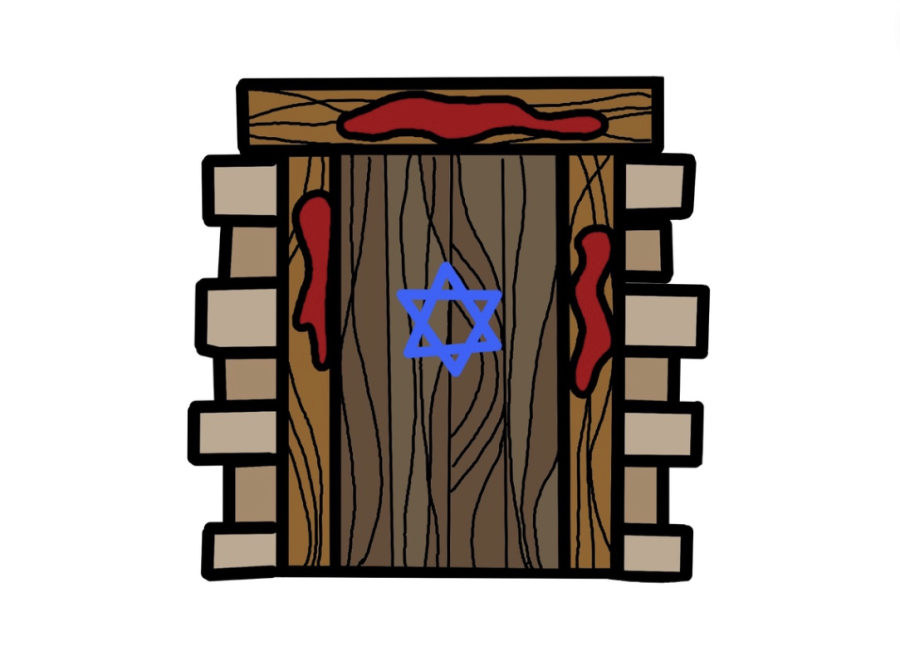

DOORPOST: In the Pesach story, blood on the doorposts of their homes kept Israelites safe during the 10th Plague.

April 20, 2023

Pesach is now behind us, and looking back on all the chaos of the climax of the Jewish calendar, something constantly crosses my mind. Why Pesach? Why is Passover the most decorated holiday of the year?

It has never made sense to me. Why not Yom Kippur, the holiest holiday, or Rosh Hashanah, the holiday that starts the new year, or even Sukkot, when we literally build a hut outside of our houses to eat in?

It just doesn’t make sense. In order to answer this question I took a deeper dive into the Pesach story, specifically Parshat Bo, where the story happens.

Over the course of my research, I came across a commentary by Rabbi Moshe Aberman in a d’var Torah he wrote for Yeshivat Har Etzion. Rabbi Aberman offers insight into this by posing another question: Why did the Israelites have to put blood on their doorposts to signify which were the Jewish homes? Would God not know which homes were Jewish and which were Egyptian?

He says that the Mekhilta, a commentary written by Rabbi Ishmael around the third century in Israel, provides an answer. The blood was not meant rather to represent where the mitzvot of brit milah (circumcision) and korban Pesach (the Passover sacrifice) had been accomplished. Then,a 12th-century midrash in the Midrash Lekech Tov of Tobiah Ben Eliezer, explains that the Jews in Egypt were actually not circumcising their baby boys.

A mitzvah as old as Avraham Avinu was no longer being practiced by the Jewish nation. A mitzvah so simple that it’s over just eight days after you’re born, so basic that it is how you start life. Even God could not understand why people were not doing it.

Midrash Lekech Tov explains: when the korban Pesach was commanded by God, Moshe told the Jewish people that it could not be eaten by anyone who had not had a brit milah. So out of fear of losing God’s protection during the 10th plague, the nation performed this mitzvah.

What this teaches us is that the mitzvah of spreading blood on the doorpost was at least partly a way for God to re-institute the most fundamental mitzvah of all, milah. Milah was the most fundamental distinction between Bnei Yisrael and other nations. It was a symbol of Jewish identity, and whether during a period of exile or when learning Torah was forbidden, there was always that distinction for our nation.

Since the time of Avraham, the time of enslavement in Egypt was the only time the Jews had not had that distinction. That is why God emphasized it so much – because it brought the nation together.

This begins to answer my initial question.

Why Pesach? No matter who you are, what you do for a living, or if you are Haredi, Reform, Conservative, or Orthodox, every Jew around the world for at least one night a year takes a moment to remember their history. It is the holiday that makes a Jew remember they are a Jew.

It is the day in the Jewish calendar when we remember where we came from and who we are. It is fundamental to our religion.

It may not be the holiest, signifying the year to come, or an uprooting of our daily lives for eight days to remember how we traveled under God’s protection in the desert. But Pesach is the holiday that represents community, that represents togetherness, that represents one nation. It reminds us of when the Jewish nation came together, rose against Pharaoh, and began our lives as the Jewish nation.

It is the time when we introduce ourselves to the rest of the world.

That is why Pesach. Because it represents the fundamental difference between Bnei Yisroel and other nations. Although old in years, Pesach is the modern symbol of Jewish identity.