When it comes to Chanukah gift-giving, the ritual is whatever you grew up with

HOME: A Boiling Point survey found that all kinds of Jews give presents — and don’t.

December 14, 2020

This Chanukah 5780, senior Yael Rubin’s family will be exchanging gifts among aunts, uncles and cousins. Dean of Students Rabbi Ari Schwarzberg will be giving gifts just to his wife and kids. Freshman Davina Benelyahu’s family and junior Benny Blacher’s family will not be exchanging presents at all.

The cultural backgrounds of those four families are different from one another — the Rubins and the Schwarzbergs identify as Ashkenazi and Modern Orthodox; while the Benelyahus are Sephardic and the Blachers are Ashkenazi and Conservative.

Most years, Yael’s family comes together with her aunts and uncles to exchange gifts each night of Chanukah (though they will not this year because of Covid). But she knows not everybody celebrates it in that way.

“My family is more traditional with gifts, but I know some of my friends’ families do potlucks and different things instead,” said Yael. “I think every family has different traditions. It depends on the specific family, and if they are really into Chanukah or giving gifts.”

It turns out Yael is right. A Boiling Point survey of Shalhevet students and rabbis revealed that the practice of gift-giving on Hanukkah has less to do with whatever religious background students identify with, and instead has much more to do with the customs of each family.

Rabbi Schwarzberg, Dean of Students and Director of the Shalhevet Institute, said he’s passing the tradition that he grew up with to his three sons, Simon, Lev and Boaz.

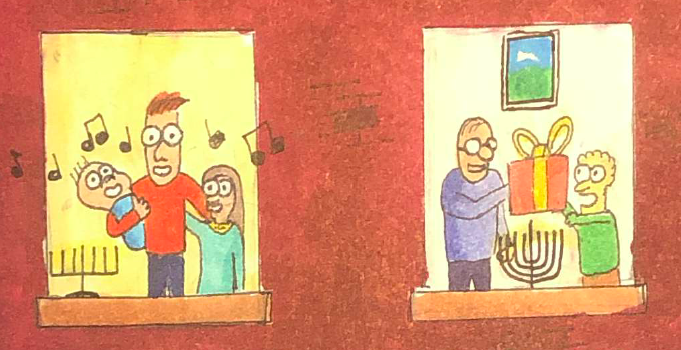

“As a parent now, we learn a lot from the way we were raised,” said Rabbi Schwarzberg. “I try to engage my kids in the story of Chanukah, we’ll play dreidel, sing, and give gifts.”

Benny Blacher received gifts for Chanukah as a child but hasn’t since fifth grade. He was one of several in the survey who said presents depend on the children’s age.

“All the kids in my class were getting gifts for Chanukah so me and my brother would say, ‘Mom, Dad, why aren’t you treating us the same,’” Benny said. “But then when we passed fifth grade our parents stopped giving us gifts.

“How I interpret it is that they don’t want to copy Christmas in terms of giving your kid a gift on the holiday and there’s nowhere in the Torah that says to give your child a gift, so my parents just thought this isn’t what the holiday is supposed to be about and they stopped doing it.”

Junior Nooria Kerendian is Sephardic and her family normally doesn’t get gifts for each other on Chanukah.

“We don’t normally do Chanukah gifts but me and my siblings are always like, ‘everyone at school or every Ashkenaz gets gifts’, so we’ve been trying to start that tradition,” Nooria said.

“I don’t know if it’s Persian or Sephardi, but it’s just not in our tradition to give gifts. I’ve asked my mom and she said it’s tradition to give money or gold coins, but gifts were never a thing.”

According to the website Chabad.org, there is no Biblical text, including the Talmud, that mentions anything about gift-giving on Chanukah.

For Sephardim, gift-giving on Hanukkah never used to be a common ritual. According to an article in the Times of Israel, rather than giving dreidels or presents to kids on Hanukkah, Sephardi Jews used dreidels to confuse the Greek and Syrian soldiers who had prohibited Jewish practices.

On the other hand, according to an article on Surf Iran, an Iranian travel and cultural website, Persian Jews traditionally give candles to their children as gifts. And like Ashkenazim, they also celebrate by eating latkes and sufganiyot and reciting the story of the oil that lasted eight days, the website said.

In the past, Jews living in America only gave gifts to one another on Purim, But according to Dr. Jonathan Sarna, Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, there was a transition from gift-giving on Purim to Chanukah in the 19th century. As Christmas became a holiday in America and a popular time for consumerism, he said, the custom turned into one that imitates the exchange of gifts on Christmas.

Rabbi Schwarzberg said there is no association between Chanukah and gift-giving in the Gemara, and that it is a tradition adopted from outside of Judaism. But he thinks it can be a good way to engage children in the holiday.

“Gift-giving is something imported from the Western world and the world of Christmas, but I think it’s wonderful,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said. “Rambam talks about how among all holidays we should give gifts and engage children with treats, so I think it’s something that has a relevance to all holidays.

“If you want people to enjoy something, especially people that are younger, you want to create a positive association with it. Why not associate Chanukah and a moment of Jewish pride and Jewish celebration with gift-giving?”

Dean of Student Life Dr. Jonathan Ravanshenas is Sephardic and would occasionally get one big gift as a child. He also practices his family’s other customs — including singing — with his children, Nava, Aharon and Levi.

“I do give gifts to my own kids,” Dr. Ravanshenas said. “We give one every night. They appreciate any gift. When they’re older it might not be as many.

“I adopted a lot of my family’s minhagim,” or customs, he said. “I love singing with my kids and we always do it together. The concept is to do it as a family.”

Dr. Ravanshenas connected gift-giving with the meaning of Chanukah.

“It’s all about bringing light,” Dr. Ravanshenas said. “So sometimes small things showing you are thinking about another person does that.

“I think this concept, especially now during the times of COVID, of bringing light in the darkness, is important,” he said. “I know a lot of people think it’s related to Christmas time and stuff like that but I look at it as the opposite, where it’s Kislev.”

Others connect gift-giving to Christmas, however.

Junior Kevin Cohen is Sephardic and gift-giving was never a tradition for his family, even as a child. If his family gives gifts, it is money.

“They’re just not really into the whole Chanukah-gifts thing,” Kevin said. “They think it’s more of a Christmas thing.

“I remember one of my friends got an apple watch for Chanukah and I was like, ‘okay that’s cool, I don’t get Chanukah gifts. It’s a pretty boring Chanukah. All the American people have their things but the Persians, from my point of view, don’t give as many gifts. It might be a cultural thing, an American cultural thing.”

Freshman Davina Benelyahu is Sephardic and her family does not formally give gifts to one another. But she plans exchanges with her friends.

“If we are going shopping my mom will say, ‘Oh, I’ll get you that for Chanukah,’ but we don’t wrap up a gift and give it to each other,” Davina said.

But she did when she was younger.

“When you’re younger your parents want to have fun with you,” she said, “and when you’re older, you can get gifts, but you’re more mature and it’s not such a playful thing.”

Sophomore Asher Taxon, who is Ashkenazi, has had a similar experience.

“This may be a maturity thing,” said Asher. “It’s more important to spend time with your family rather than buy each other gifts. We usually get presents that we’ve been wanting or something that we thought would be nice.”

Sophomore Maddie Bollag is Ashkenazi and always gets gifts on Chanukah.

“Usually we’ll do a really small gift every night or we can choose one big gift for the whole Chanukah,” said Maddie. “My dad is Ashkenaz and he said he would never get gifts on Chanukah. Usually my Sephardic friends get more gifts.”

Freshman Elishai Khoobian is Sephardic and his family gets gifts based on what they ask for. This year he is asking for shoes.

“My parents don’t really care about the gifts,” Elishai said. “They ask me what I want and I just tell them, it’s not something with a lot of effort.”

At least in the Shalhevet community, gift-giving on Chanukah does not seem to be unique to any Jewish denomination or group. Rather — as with many Jewish practices — the tradition truly depends on the customs of parents’ parents.

It may have evolved through centuries of living amidst celebrations of Christmas, or in the case of more recent immigrants, amidst Jews who at this point associate presents with Chanukah.

Is there a danger, then, that Chanukah — perhaps like Christmas — could become too commercialized?

“I guess the problem can happen if the holiday only becomes associated with gift-giving, as opposed to the Chanukiah and the story itself,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said. “Then it’s become too distant from the actual meaning of the holiday. But in my experience, I think it only enhances what people know about the holiday.”

Editor-in-Chief Molly Litvak contributed to this story.