‘Holy conduct’: How to be Jewish during a hard election season

Photos from NSPA/ACP by Carter Marks – Royal Media and Nikolas Liepins

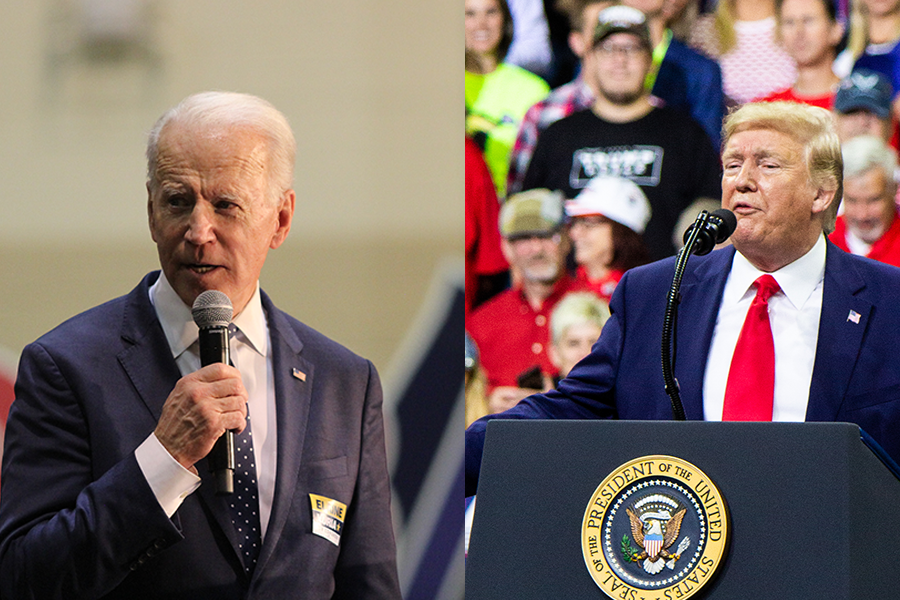

GIFT: At the end of a divisive presidential campaign, Rabbi Yosef Kanesfky told his congregation that from a religious perspective, democracy is a gift that we have been empowered with “to impact and affect the lives of other human beings.”

In an email to his congregation last Tuesday, Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky of B’nai David-Judea Congregation in Pico-Robertson said Jews of all political beliefs should aspire to holiness during the current 2020 election season. Editor-in-Chief Molly Litvak interviewed him about the email two days later, and below is an unedited transcript of their interview.

The Boiling Point: What inspired you to write this teaching?

Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky: The theme of being able to engage one another over disagreements and to listen to one another and to recognize the value statements in the other’s position has been something that I’ve been talking about for years now as the political climate has deteriorated into so much ad hominem rhetoric. As the election drew closer and closer, I was trying to think of what I can as a rabbi contribute to this very intense, potentially divisive, potentially even violent moment that we’re approaching. What can I contribute that might make it a little bit better? And that’s what led me to think about what are the ethical guidelines, what are the religious guidelines, what does our tradition teach us about how we conduct ourselves in general and in particular when the pressure is on.

BP: What is an example of “holy conduct” in relation to this period before the election?

Rabbi Kanefsky: Well, holy conduct means a lot of things, but one thing that holy conduct certainly means is looking other people in the eye and, before saying or doing anything, remembering that like you, this is a person who is created in the image of God, who is deserving of fundamental respect, who is possessing dignity. And that’s the way that this conversation needs to be engaged. That’s one example of what it means to conduct oneself in a holy way.

How can we engage in respectful dialogue with those holding opposition viewpoints if their beliefs personally offend us?

There’s a lot of steps there. You can’t really do it unless there is a prior relationship. You can’t do it in a vacuum; it’s not going to work. The pre-step is cultivating relationships very deliberately with the people in your community with whom you disagree, so that there’s a context of a relationship that’s broader and bigger than just the issue or issues you disagree about. That’s the prestep that always has to be consciously carried out. You want to do this sort of thing.

The other thing is to get out of public, to try to create a private space, so neither one of the interlocutors is worried about what someone else is hearing, isn’t trying to score points in the eyes of someone else. It’s very important to talk in private.

And it’s very very important to say, ‘I want to meet with you because I want to understand what you are thinking,’ rather than saying ‘I want to meet with you because I want to tell you what I’m thinking.’

BP: What are examples of ways we can maintain goodness in accordance with Judaism when getting triggered or heated in the moment?

Rabbi Kanefsky: There’s an expression that, I don’t know where it comes from, but it was very popular at one point back when I was a college student at YU: Ein kedusha b’li hachana — it’s impossible to attain holiness, or in this case goodness, without preparation. The less we can allow ourselves to be triggered, the more we can say ‘I would like to respond to you, but I would like to do so when we are both calm, because it will be a much better conversation, so I’m just going to hold back now.’ That way you make it clear you’ve got something to say, but you’re just afraid that if you say it right now it’s going to be counterproductive and it’s going to do harm, rather than being productive and doing good.

BP:What hostility have you seen in relation to the upcoming election?

Rabbi Kanefsky:When we look around, it’s the epicenter in terms of the Orthodox community now in New York, with a lot going on. Really a tremendous amount of anger, hostility, fury, and assertiveness and combativeness. It’s in the national newspapers every day. Thank God it’s not as bad here, for all kinds of reasons.

BP:Have you seen this hostility particularly in the Jewish community? If so, what and where and when?

Rabbi Kanefsky: I mean, that’s where I live, that’s where we live, so that’s what we see. I’ve certainly heard of tremendously, almost abusive exchanges on Facebook among people who I know they know each other, I know they go to simchas together, I know their kids are in the same school, and I hear about the language that people are using. The invective that people utilize, the names they call each other, the sarcasm — I mean, this is bad stuff.

BP: If the election results don’t turn out as we had hoped, how can we, as Jews, cope?

Rabbi Kanefsky: There’s no one answer to that. Everyone has to do that their own way. For some people, it will mean an even more robust engagement in the political process, for others it will mean total withdrawal from the political process, and neither one of those is right or wrong. It really depends on the person.

The most important thing — and this will be the work that needs to be done after the election is over — is for people to be reminded in every way that we can remind them, that we are an eternal people and there are things that are at the core of our identity as Jews, and those things remain true and important no matter what happens. It’s the same things that have been true and important for thousands of years, when we have made our way through all kinds of hardships and difficult circumstances. And to come back to the things we believe in, the things we’re committed to, and do what we always do: figure out how in the circumstances we find ourselves in. We realize and devote ourselves to the things we really believe in.

BP: Is it our responsibility, as Jews, to be active in encouraging people to vote and keeping up to date with politics? Why or why not?

Rabbi Kanefsky: One hundred percent. Politics isn’t politics, politics is about life. It’s about justice, it’s about who gets to eat and who doesn’t get to eat, who gets to be educated and who doesn’t get to be educated, who has healthcare and who doesn’t have healthcare. And there can be different political avenues for achieving those goals, and there can be very legitimate disagreement as to how those goals are to be realized, but that’s what politics is about. It’s about people and human welfare.

BP: In relation to your last guideline, how can we turn the situation for the better if we disagree with the election results or if we get in a political fight with someone?

Rabbi Kanefsky: There are things that are out of our control. If the election results are not what we would have wanted, there isn’t so much. We have to recognize what our limits are. What we can do [if the results are what we wanted] is to reach out to someone on the losing side, and say ‘I’m very happy with the election results. I have a feeling that you’re not. And I just wanted to reach out and express that I recognize that you’re feeling very disappointed, express my empathy, and if you want to talk, I’d love to talk.’

BP: There was no democracy, there were no elections when the Torah and Talmud were written, right? How then can we know what the Torah would have said about a time such as this, when so much responsibility is in our hands?

Rabbi Kanefsky:I think this goes back to democracy simply being the way that we have been empowered to impact and affect the lives of other human beings. In that sense, we are always called upon to devote whatever particular gifts we’ve been given — and we’ve all been given different gifts — to use our gifts for the betterment of God’s world. Whatever that gift may be, one of the gifts that we’ve been given in this particular moment is the gift of democracy, so this is one of the gifts that we are now bidden to utilize for the sake of human welfare and the betterment of human society. It’s just a matter of which gift you have in any given moment of human history.

Molly is studying at Midreshet Torah v'Avodah seminary in Jerusalem and will attend Columbia University in New York next year.