Rabbanit tells senior girls: ‘We need you within the Torah world’

As holiday observances can change, so can roles and opportunities for women in Jewish practice, leader of Nishmat tells class

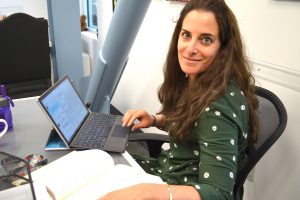

BP Photo by Jordana Glouberman.

Meeting during Period E in Room 304, Rabbanit Henkin said future leaders of Jewish learning would come from today’s talmidot, or female students of Torah.

‘In the 12th century, there was no holiday of Simchat Torah.

In the 14th century, it was celebrated in part by pre-bar-mitzvah-age children lighting bonfires from stolen parts of their sukkot — a minhag, or custom, which quickly faded out of practice.

And by the 16th century, Simchat Torah celebrations were similar to today’s.

Throughout all that time, there were no changes at all in the religious roles of Jewish women. But Rabbanit Chana Henkin, leader of the famed Nishmat women’s seminary in Israel, said that some specifics of women’s roles are minhag, too — and are changing now, in the 21st century.

Rabbanit Henkin, who spoke to the 12th-grade Advanced Tanakh class last Tuesday, said that today’s changes will be remembered and will shape the future.

“In another 200 years when someone’s delivering this shiur,” Rabbanit Henkin said, “and they’re looking at these points in which there were changes, they’re gonna say in the 12th century here’s what it was, and in the 14th century here’s what it moved on to, and in the 16th century here’s what it moved on to.

“And I think that person’s going to say that in the 21st century something happened, because there was a sociological change in Jewish life.”

A major advance in women’s Jewish learning in the late 20th century led to results that are being seen now, she said.

Why now?

“Because women began getting advanced Torah education,” she said, “and because women began saying, I don’t want a role in which I am a spectator, I want to feel a part of this, this holiday belongs no less to me.”

In preparing students for Rabbanit Henkin’s visit, Yoetzet Halacha Atara Segal described her as one of the top three most impactful women in Orthodox Judaism today. About 30 students were present for the talk during Block E in Room 304.

Nishmat, located in Jerusalem, is best known for creating and developing the role of the yoetzet halacha, or Jewish legal adviser, which trains women to answer the most advanced halachic questions about health- and marital-related Jewish observance. This means observant women can ask a trained woman about these issues, instead of having to visit an Orthodox rabbi.

But it also offers a gap year program, shorter programs for non-Israelis, and institutes for post-IDF and national service Israeli women and Israelis of Ethiopian descent.

Yoetzet Segal, who completed her training at Nishmat last summer,.said Rabbanit Henkin was visiting the U.S. to discuss the program, teach courses to U.S.-based students enrolled in it, and visit area Orthodox high schools, where she encouraged female students to take their Jewish roles seriously.

“Here’s what I want to say to the young women sitting here,” Rabbanit Henkin said. “I want to tell you that we need you. We need you within the Torah world.”

Rabbanit Henkin told the class that she’d found the potential for a progression in women’s roles in studying the fluidity of ancient minhag. Another example was a 14th-century custom of singing songs over Sifrei Torah.

“Each place according to its own minhag,” she said. “Do you know why it was so important for me to read this?” Rabbanit Henkin asked her audience of 30. “It’s important to see that customs change within Jewish life, that things change within Jewish life.”

Rabbanit Henkin most recently published a book of she’elot and tshuvot, or questions and responses, called Sefer Nishmat Habayit, written entirely by women. The book features halachic questions and answers and seen as a source of guidance for both men and women in making religious decisions.

“I don’t live in a world of being fearful of slippery slopes. I’m more afraid of not including women.

— Rabbanit Henkin

Nishmat’s platfom for receiving questions is on its Yoetzet Halacha website, which receives questions from Jews worldwide on the intersection of women’s health and sexuality with Jewish law. It has gotten over 300,000 questions to date.

Rabbanit Henkin began her work after noticing an absence of women’s voices in discussions of laws relating to Jewish families.

“When we started out, there were no women addressing questions about family or women’s health, and I said to myself, ‘how can this be? The time has come,’” she said. “Hasn’t the world noticed that today we have women who are rocket scientists, Nobel Prize winners? What do we [in Orthodox Judaism] think women are?”

Rabbanit Henkin said that though she has worked to increase opportunities for women in Orthodoxy, the next generation will control what comes next. She urged the female students present to engage in Torah learning and make it a priority in their lives.

“If the talmidot chachachim of the next generation don’t come from you, then where are they going to come from?” she said. “I’m enabling your generation to do what it’s doing, but this is something which you, as observant Jewish women, and the men who are going to provide support, need to articulate the custom.”

For those who worry that such changes challenge actual Jewish law, or halacha, Rabbanit Henkin made practical distinctions between law and custom. She said that while one is stagnant, the other is malleable — and that women’s roles are in the latter category.

“This is not halacha,” Rabbanit Henkin said. “Customs have to do with the color of Jewish life.

“We deal with halacha — we deal with that which is clear — but there’s also another part of Jewish life which is extremely important, which is customs,” she continued. “Customs have a way of appearing sometimes to stay, and as you saw with the [Simchat Torah] bonfire, sometimes they’re here not to stay.”

One shift in custom that she said expands women’s opportunities involves blowing the shofar, which women do at Nishmat.

“There’s no reason that a woman shouldn’t be allowed to blow the shofar instead of a man,” she said. “You can’t have a makhloket,” or religious dispute, “for that, unless you say women shouldn’t do that lest it be a slippery slope because they’ll think that they can then do other things.

“But I don’t live in a world of being fearful of slippery slopes. I fear more not involving women.”

She said her goal was not that women’s and men’s roles should be the same, but that women be enabled to live lives in which high-level Torah learning is an everyday part of their lives, and something to which they can contribute.

What she discovered in her own learning — including examples like the evolution of Simchat Torah — affirmed her belief that this was possible.

“I’m not in favor of radical equality,” she said. “I’m in favor of every person as a person, every gender as a gender, maximizing themselves as ovdei Hashem” – servants of God.

“I want you to make Torah learning a part of your life where your neshama,” or soul, ”says: in terms of my priorities, this is a top.”

Lucy Fried was co-editor-in-chief during the 2018-19 school year and went on to study at the Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. She is now a junior at UC Berkeley.