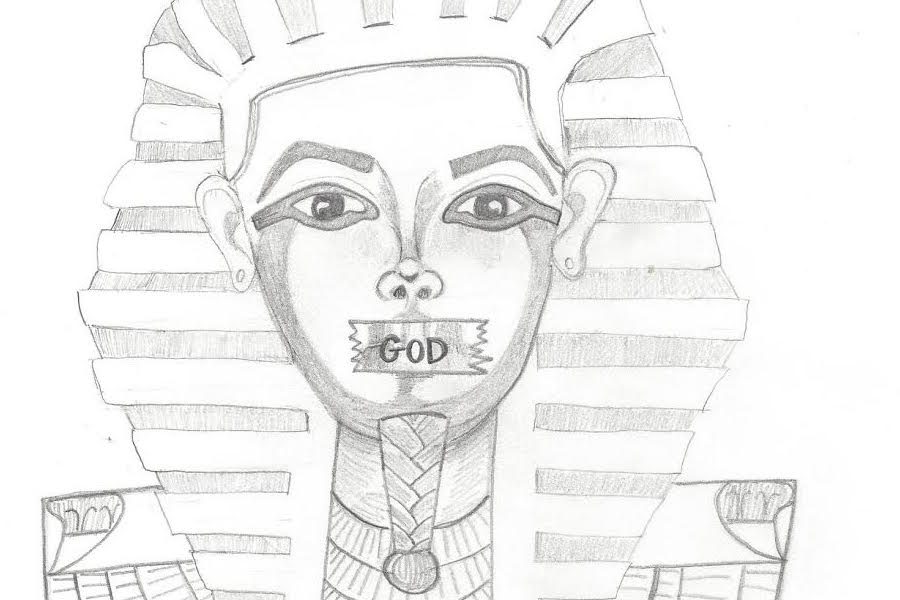

Parshat Bo: The message of a hardened heart

January 19, 2018

By Rachel Lasry, Staff Writer

In this week’s parsha, Parshat Bo, Pharaoh agrees to release the Israelites after God begins the plagues against his nation. God realizes that Pharoah has agreed to this not because he found faith, but to stop the plagues. So God “hardened” Pharoah’s heart, the Torah tells us, making the Egyptian ruler not want to let them go after all.

The remainder of the parsha describes the final three plagues God inflicts upon the Egyptians. After locusts and palpable darkness, the last plague is the worst of them all: makkat bechorot, the death of the firstborns. Finally the Jews are liberated, and during their exodus, Moses is presented with the Ten Commandments.

In hardening the heart of the ruler of Egypt — in effect, by forcing him to sin — God demonstrates that teshuva, or repentance, is a privilege rather than a right, and in fact He can take it away if it is taken for granted one too many times. With the seventh plague comes Pharaoh’s compliance, which is what one would expect God wanted. However, God prevented this by “hardening Pharaoh’s heart,” leading to the plagues’ resumption.

Rambam, the most influential Torah commentator of the middle ages, states that God actually never wanted Pharaoh’s compliance alone, but rather his true Teshuva and faith. He considers Pharaoh’s change of heart a practical move to end the plagues – not a sign that he’d changed his belief.

A hundred years later, Ramban, the philosopher, kabbalist and biblical commentator, said that God’s interference was actually a last resort. When after seven plagues, Pharoah still hadn’t gotten the message, so God decided that any repentance made from this point on would simply be to end the plagues, not due to a recognition or awe of God.

In addition to these commentaries, there is that of the acclaimed Sforno, who agrees with the Rambam and the Ramban that obedience without repentance does not warrant God’s forgiveness or mercy.

From this wisdom we can deduce that everyone is given many chances at repentance, but there is a limit to the number of times one can miss the opportunity to start over.

This may appear harsh or unfair, however we must remember that as humans we are reflections of God. We too have our limits when it comes to providing chances to those who have ceased to change their ways. How can we expect more from God who Himself can sense when one’s repentance is ingenuine?

Judaism has always considered repentance an act of great importance. To allow it to become something that anyone can achieve at any time, even with the wrong sentiment, would be cheating it of its significance. The opportunity for change is a privilege, and it is not unlimited.

Perhaps free will, too, is a privilege, rather than a right. The ability to make our own decisions, with our own minds and our own sentiment, is actually a gift — and a gift that is not to be taken for granted. Freedom is never unlimited. Maybe it is handed out in slices, in even amounts dispersed among each soul on our earth. These slices of control are priceless and will be confiscated if they are abused.

Like Pharaoh, those of us who exploit the power given to them by God can ultimately lose the ability to make certain decisions for ourselves. After all, life is a test, and who’s to say that we have unlimited chances to pass?

Free will is a gift and should be treated as such, for without it we would be souls stuck in limbo, with no room for growth in the future. The course life takes is entirely based on the choices we make and the sentiments behind them. We mustn’t forget that our actions have consequences. Self-control is a God-given gift, not a right, and can certainly be taken away.

That is something we can learn from God hardening Pharoah’s heart. Though we’re not leaders of nations ourselves, understanding this means recognizing our own tremendous responsibility and power.