Town Hall debates who should shush

QUIET: Students concentrated on one thing or another during Mincha Feb. 20, when students were supervising behavior at Mincha. Also at issue lately has been who should be responsible for food clean-up after breakfast and lunch.

March 10, 2014

At the close of a Town Hall devoted to davening behavior and food cleanup issues, Head of School Rabbi Ari Segal turned the running of Mincha over to students instead of the Judaic Studies staff Feb. 6 – but it turned out to be temporary.

The change was meant to solve three problems that had been addressed during Town Hall Feb. 6: students’ talking during davening, teachers’ attempts to stop the talking, and students being unable to concentrate on their prayers because the teachers were distracting them by shushing talkers, particularly by using the microphone to stop the service.

“I have asked the Judaic faculty not to be in davening for the next few days,” announced Rabbi Segal just seconds after the bell rang to start Mincha.

Davening started moments later with no Judaic Studies teachers in the room. There seemed to be no talking at all during that day’s davening. Students arrived home that night to find a short letter from Rabbi Segal posted onto their Schoology pages.

“While I admit I was a bit disappointed by the lack of responsibility-taking and the ubiquitous finger-pointing at today’s Town Hall,” wrote Rabbi Segal, “I am willing to acknowledge that allowing you to monitor your own tefilah [prayer] may be a more productive option.”

The policy lasted for three weeks. At first students were very quiet, and Rabbi Segal was happy with the change. But gradually the noise returned, and with teachers unable to interfere, on Feb. 25 the experiment was declared over.

“I would love to hear your feedback if you feel differently, but I have to say the results speak pretty unequivocally for themselves – it isn’t better this way,” Rabbi Segal wrote in a Student Activities post on Schoology. “Perhaps in the future, after the culture has improved, but not yet.”

He went on to say the Judaic Studies faculty would meet, “and I am guessing we are going to revert back to faculty leadership of the minyanim for the next few weeks.”

The next day, teachers were back to shushing people, waiting for quiet before starting, and stopping the service when the noise got too loud. However, as of March 3, the microphone had not been used.

During the Feb. 6 Town Hall, a lengthy discussion about the davening behavior showed a strong disconnect between how students and faculty viewed the situation. Also on the agenda was some students’ failure to clean up after eating breakfast and lunch.

The meeting ended without a plan for the food cleanup issue.

But the davening issue saw both discussion and action. Teachers said that when students talk, they approach them and ask them to stop. If that doesn’t work, they use the microphone to stop davening until the room is quiet — making Mincha longer and the post-Mincha break shorter. Students complained about this stopping.

“When teachers use the microphone it disrupts my davening even more than the small whispers around me, and I kind of just lose kavanna,” or focus, said junior Rina Katzovitz.

The Judaic staff replied that they are ignored when they speak to students individually.

“I’ve ruined relationships with students over telling them to be quiet,” said Judiac Studies teacher Reb Tuli Skaist. “I feel like a tape recorder telling students to be quiet.”

Some students suggested dividing into smaller groups and creating different kinds of davening or changing the mood so people would like it better. However, Rabbi Segal thought that perhaps students might listen better to each other than to teachers, and might even succeed at creating a quieter environment for prayer on their own.

That afternoon, the students efficiently set up the mechitza, handed out siddurs to one another, and delivered a strong Mincha without any chatter.

“I find that davening has been a lot quieter recently because the teachers don’t get up and make announcements anymore,” said sophomore Daniel Shoham a few days later. “I find it more effective and less disruptive when students go up to other students and tell them that they are disrupting others.”

Teachers said one problem with controlling davening was that it’s not an academic subject counted in the GPA – and that the same problem extends to getting students to clean up after they eat. They said cereal bowls are left outside the doors of their classrooms and sometimes spill on the floor.

Director of Admission Ms. Natalie Weiss said she is sometimes embarrassed to take prospective students and parents on tours around the school because of used bowls and plates left out in the hallways.

“We should have a rotation by grade that hangs out for the last two minutes of lunch and cleans the tables on behalf of everybody,” Ms. Weiss said.

But taking over food cleanup was not met with the same enthusiasm as taking charge of davening behavior. The concept of toranut, or taking turns, was dismissed after students said that they did not want to clean up other peoples’ messes.

Math and science teacher Mr. Christopher Buckley suggested giving the custodians time off, turning clean-up over to the entire student body at once.

“Let’s have the custodians take a few weeks off so we can see how nasty the school can get,” said Mr. Buckley.

The davening policy at Shalhevet has always been that students are not required to daven under the condition that they hold a siddur in their hands and do not talk to others. However, some students have used davening as a time to socialize with their friends and use their phones.

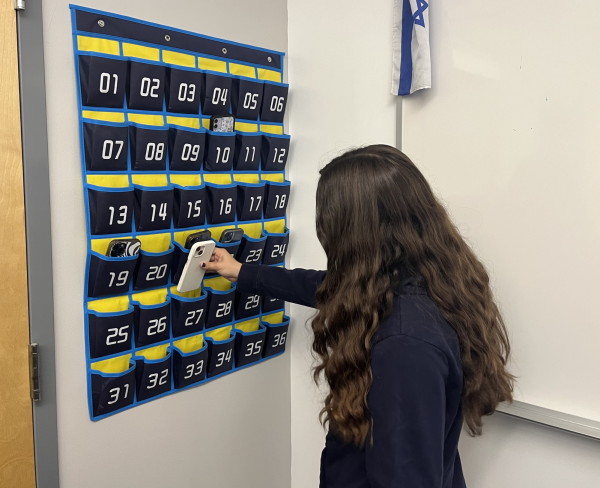

Right after Rabbi Segal announced that Judaic teachers would again be allowed to supervise davening, he walked up to a group of girls who were sitting in the back row, pinpointed a girl who was using her cellphone, and took it away. “It was like she was waiting for that moment her entire life,” said sophomore Shir Zahavi.