In the opening weeks of school last fall, at least five students learned that a parent was suffering from some form of cancer. Since enrollment at Shalhevet hovers around 160 students, everyone knew someone affected, and the whole community was drawn closer together.

At the same time, student concern for Israel was higher than usual. Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons was a frequent topic in the presidential election campaign, and crises in Libya, Egypt and Syria made the Middle East tense.

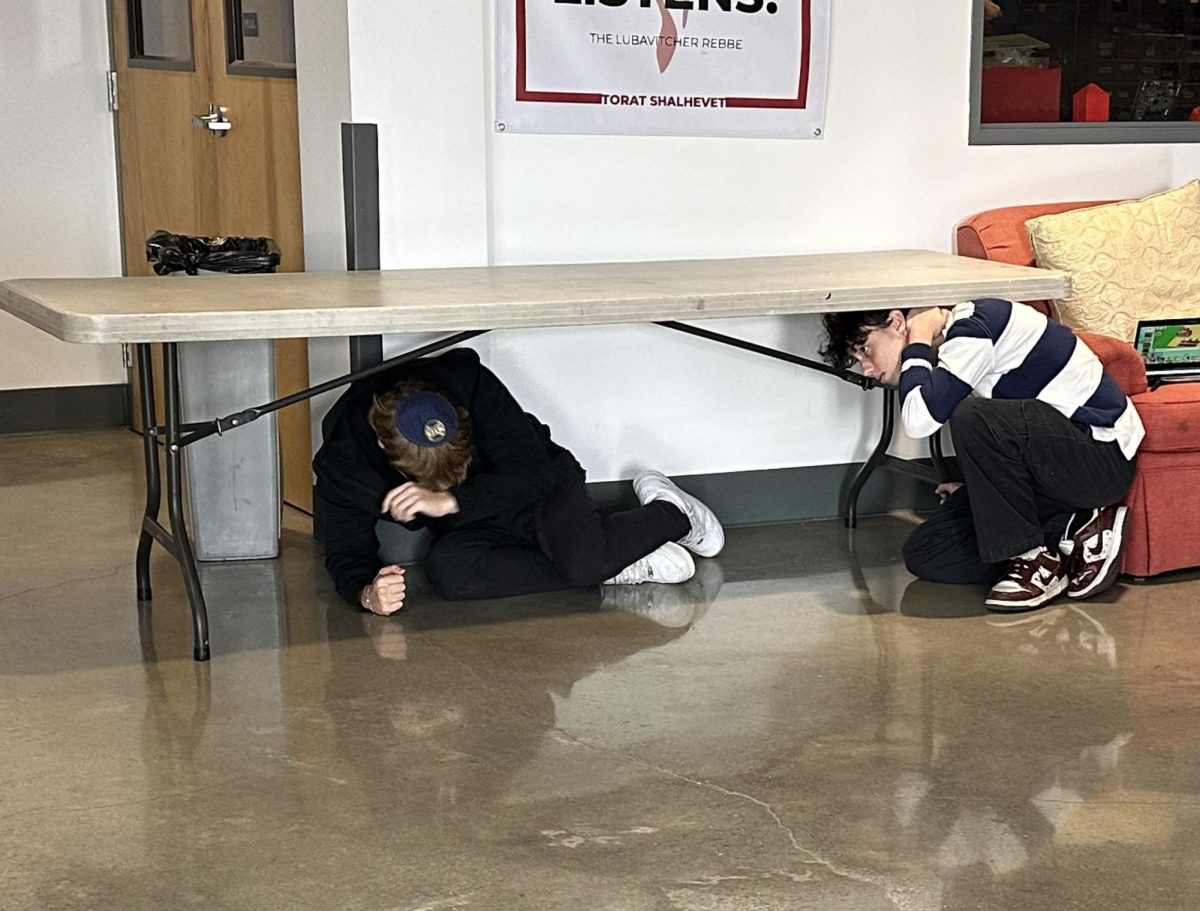

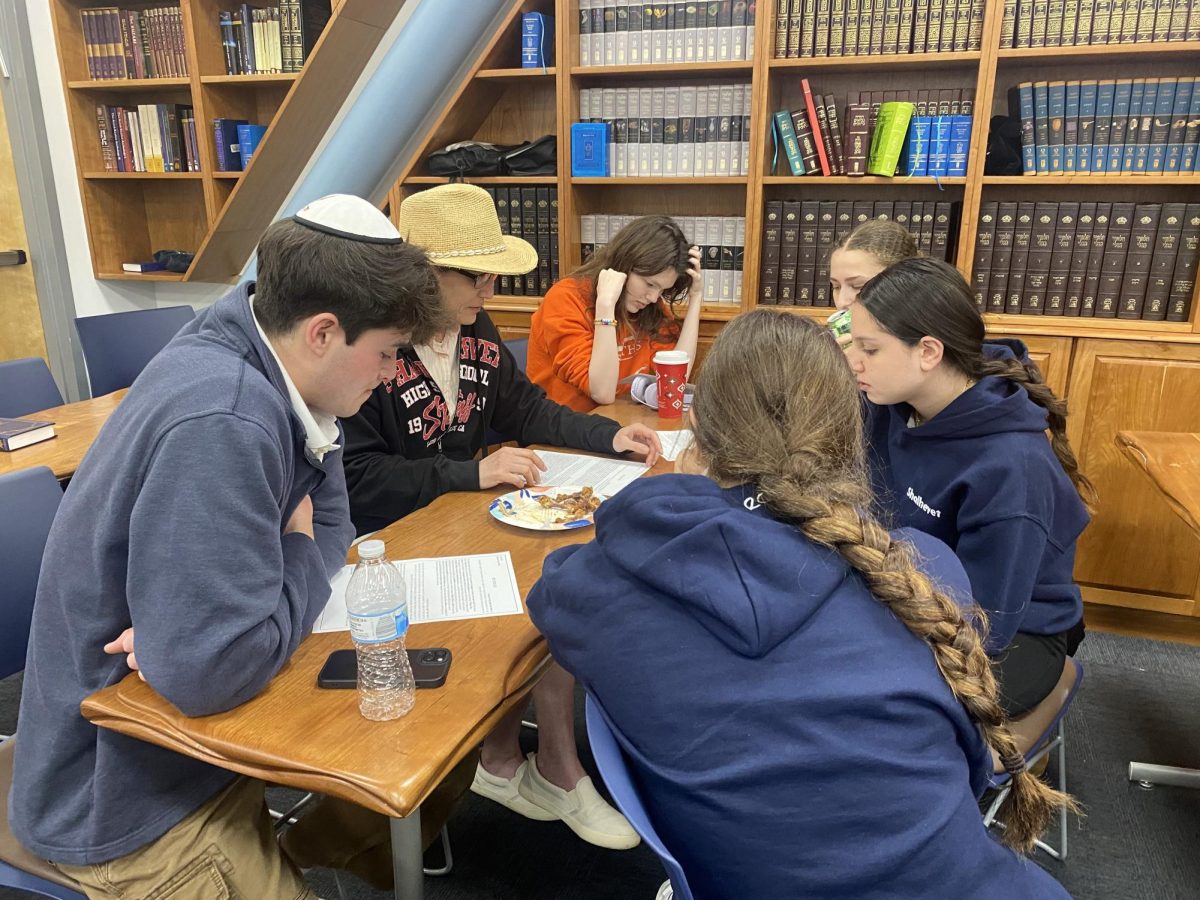

So it was perhaps inevitable that shared concern would translate into davening — partly in increased kavanah (intention), and partly in the addition of optional prayers. By late November, Shalhevet’s main minyan had instituted three new traditions: depending on the day, the reciting of Tehillim (psalms) and-or a misheberach for the sick, and the addition of a misheberach for the strength of Israeli soldiers.

Everyone seems happy with the additions, but none more so than students whose parents are ill.

“It just makes me feel so much better that the whole community has my back and is praying for the well-being of my family member,” said a male student whose father is in need of prayer. (He did not want his name to be used.) “I think that it is really great that we pray for the sick.”

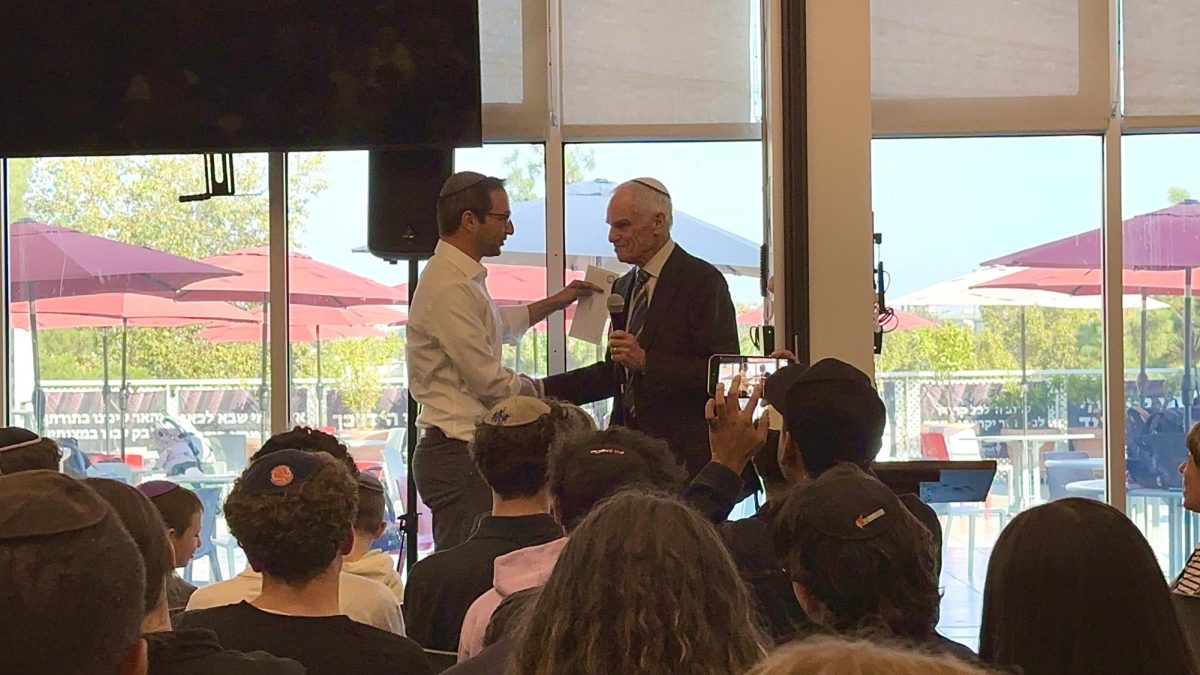

Judaic studies teacher Mr. Jason Feld said he thought the prayer for the welfare of Israeli soldiers could help keep Israel in the forefront of students’ thoughts.

In fact, he said the idea for the addition came from students, during a project with his sophomore Modern Jewish History class about what it means to be active Zionists. The students decided adding a prayerfor the IDF every day during Shacharit would enhance Shalhevet’s support of Israel.

“It absolutely affects the culture of Zionism in our school,” said Mr. Feld.

According to the leaders of the minyans, these prayers are meant to accomplish two goals: uniting the Shalhevet congregation through prayer, and supporting and strengthening the soldiers and community members. Yet Judaism has a complicated relationship with the idea of influencing God through human action.

Jews are commanded to pray three times a day, according to a set liturgy of praise, thanks and requests. Among the requests are wisdom, health, rain, dew and peace.

After parents and relatives of Shalhevet students became sick last fall, via email Judaic Studies Principal Reb Noam Weissman compiled a list of their Hebrew names, which Reb Tuli Skaist now rattles off after davening or after the Torah reading, depending on the day of the week.

Around the same time, rabbis in the Main Minyan added a daily psalm, Psalm 130 – which includes “Lord, hearken unto my voice; let Thine ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications” and is recited daily in many shuls for the healing of the sick. On non-Torah reading days, Reb Tuli leads it line-by-line responsively with the congregation at the end of tefilah (prayer).

The Sephardic minyan says a misheberach for the IDF every day, and upon rare request adds also aprayer for the sick.

So named because it begins with the Hebrew word misheberach, which means “He who blessed,” the misheberach prayer for the sick begins, “He who blessed our forefathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, may He also bless ….” Then names of the sick are then added, or in the case of the IDF, “tzava haganah l’yisrael” – the force defending Israel.

In the misheberach for cholim (those who are ill), the text directly asks God to intervene on their behalf and grant them a refuat hanefesh u’refuat haguf – a complete healing of mind and body. In the case of the IDF, it asks for soldiers’ safety and victory.

But Jewish tradition is unsure about whether this “works,” in the sense of influencing God Himself. If it does, then does that mean God doesn’t have a mind of His own? And if it doesn’t, then why do we ask?

“I believe the words that I say, and yes I believe that prayer is extremely powerful and has the power to change a situation,” said Reb Tuli in an interview. “I feel honored to lead the tefilah on behalf of those who are ill.”

Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Ari Schwarzberg views the prayers somewhat differently.

“I personally believe its impact is less supernatural, and more about our sensitivity and concern for those who need arefuah shelaima,” Rabbi Schwarzberg told The Boiling Point.

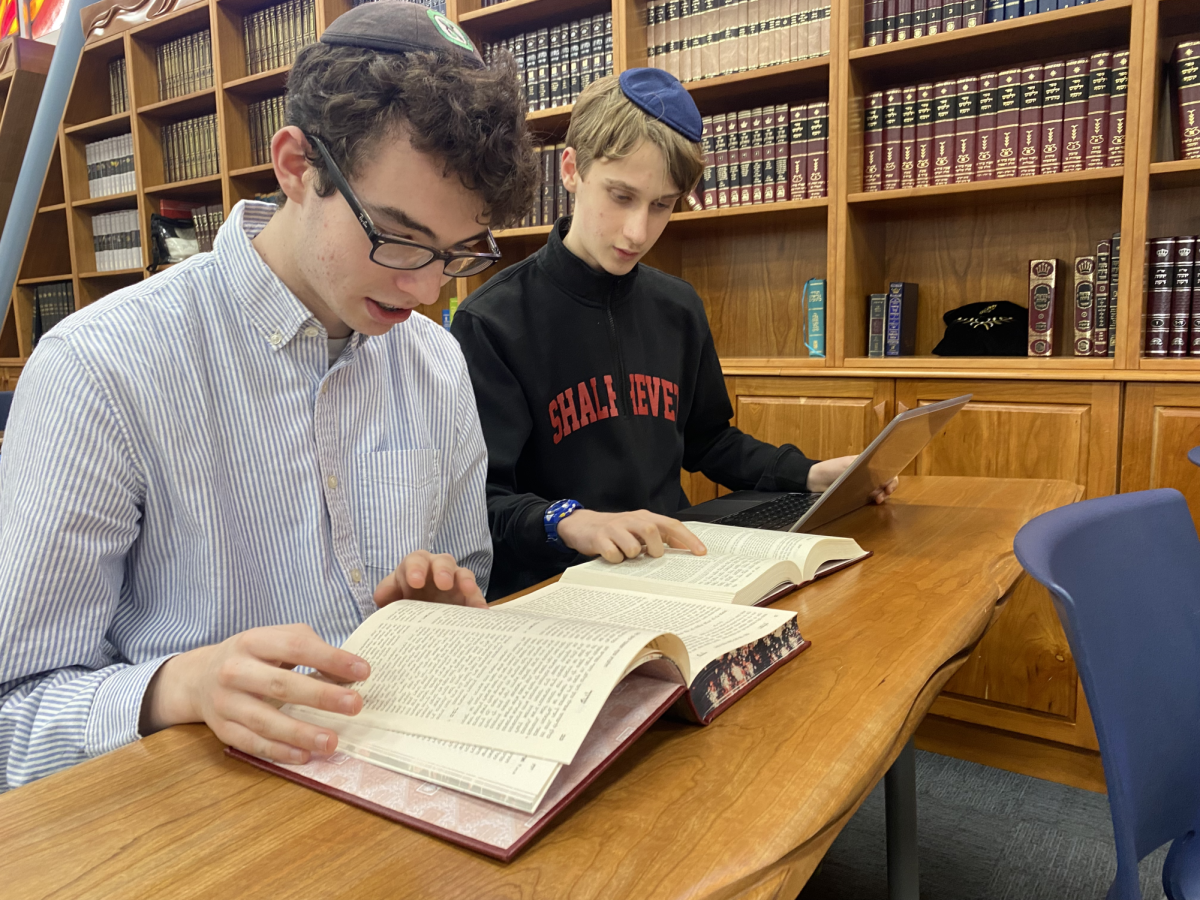

In a long history of wrestling with these questions, the most recent opinions seem to suggest that prayers do not necessarily heal the sick or even are listened to by God, while older writings imply the contrary.

The Gemara in Yevamos 64a states that “The Holy One, blessed be He, longs to hear the prayer of the righteous.” This explanation means that God wants to be prayed to.

Similarly, Ketubot 104a records that the story of Rabbi Judah, who was dying and whose students would never stop praying for his life. The moment when they ceased to pray for him due to a distraction, the Gemarah says, “his soul departed.” This suggests belief in a supernatural impact of prayer.

Another way of looking at it comes from Rabbi Avraham Twerski, a Milwaukee native who has written countless books and composed numerous Torah shiurim while being a psychiatrist. Rabbi Twerski believes that prayer works, but not in ways that we can see.

He gives the example of someone who is healed indirectly by the prayers of others.

“For reasons known only to God, Divine justice may decree that a particular person must undergo suffering,” Rabbi Twerski wrote on torah.org. “This person shares his pain with a friend, who is so moved by his friend’s distress that he suffers along with him and prays for him. However, Divine justice never decreed that the second person suffer.

“Therefore, in order to relieve the friend from unwarranted suffering, Divine justice requires that the first person be relieved of his distress.”

However, most recent opinions say there is no guarantee that God will grant prayers, nor is it certain that He consistently can.

The Rambam seems to say it is blasphemous to even imagine that anyone can influence the will of God. Those who take for granted that God will be affected by your prayers “unconsciously at least incur the guilt of profanity and blasphemy,” states Rambam in Moreh Nevuchim Ch. 36.

Rabbi Schwarzberg seems to agree with the Rambam:

“It would be blasphemous and educationally dangerous to claim that tefilah will necessarily improve the fate of the ill — what if fate decides otherwise?” Rabbi Schwarzberg said. “We must be very careful not to throw around false perceptions of God.”

But he acknowledged that it is part of our tradition anyway, and has value whether it influences God or not.

“Jewish tradition affirms the value of praying for those who are ill, and at the very least it can have certain psychological benefits,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said. “I think that throughout our history, the Jewish people have valued the institution of praying for those who are ill, many assuming that tefilah possesses the ability to influence someone’s medical condition.”

What about people who are naturally turned off from believing in God, and from prayer, if their desired results don’t happen? This does not create a problem for the Rambam, who says you can surely not blame God since you can’t rely on the effectiveness of prayer.

Rabbi Marc D. Angel, a renowned Modern Orthodox thinker and founder of the Jewish Institute for Ideas and Ideals, shares this view.

“If we use the words of the Torah and Tehillim as though they are some magical formula that we can somehow manipulate God to fulfill our will, [then we] deny the Torah,” says Rabbi Angel, applying Rambam’s laws regarding idolatry in an online video.

Additionally, the siddur Avodas Halev says that “the agadic (anecdotal) statements according to their outward appearances, without understanding their deep meaning, are prone to cause the blind to go astray on the way and to lead them to darkness and not light” (Otzar Hatefillos p.20). He says you cannot trust a fable and take it realistically, therefore God does not for certain react to human prayers.

Nevertheless, Reb Noam Weissman feels the practice is important, and so, it seems, does most of the Shalhevet community.

“It’s important to demonstrate care for and pray for the sick people in our community,” said Reb Noam.

A girl whose father has been undergoing medical treatment this year said the misheberach is the only part of the service she prays.

“I’m not really connected to davening at all, but when the prayer is said out loud it is the only prayerthat I will say,” said the girl, did not want her name to be used in this story. “I think it’s really important, because if you don’t want to daven it gives you an opportunity to still pray for the sick.”

Students who are not praying for a personal loved one also get something out of it. For example, sophomore Zev Marcus is designated to select a different student, boy or girl, every day to recite the prayer in the Main Minyan for the IDF.

“The way I get connected is by having the honor to choose someone to do it every day,” said Zev.

Mr. Feld believes it’s working at least on that basis.

“I do believe it has a apiritual impact,” Mr. Feld said. “We spend some time reflecting what our Israeli brothers and sisters are sacrificing in Israel.”

How can prayer be effective, important and possibly blasphemous all at the same time?

Rabbi Schwarzberg said the answer is complicated – like Judaism.

“It is a truly remarkable element of most faith communities [that] religion, in its singular fashion, simultaneously allows, perhaps encourages, conflicting thoughts and emotions,” Rabbi Schwarzberg wrote in an e-mail to The Boiling Point.

“On the one hand, praying for the sick is an integral part of our compassionate behavior, but taken too far it may undermine fundamental religious precepts,” he continued.

“Such nuance bespeaks the sophisticated nature of Jewish thought and proves that religion only becomes properly appreciated and understood after careful study and profound introspection. The uneducated Jew cannot penetrate its depths.”

For students who are actively praying, hope seems to be part of the equation, too.

“I’m hoping that through the communal prayer, as long as they are praying every day, a good result will come of it,” said one of the anonymous students whose parent is ill.

Whatever the actual effect of their prayers, the Shalhevet community hopes so too.