Their voices rolling with a North African lilt, students in the two-month old Sephardic minyan sing to a different melody than Shalhevet’s two Ashkenazic minyans.

For the first time since about 2001, Shalhevet’s Sephardic students have a minyan they can call their own. Although there is increased interest among its 26 members to learn how to lead the fast-paced service, many simply enjoy being there because it’s what they’re used to, and a part of their heritage.

The term Sephardim literally describes Jews whose ancestors emigrated from what is now Spain during the Spanish Inquisition. But it’s also used to describe so-called Mizrahi (“Eastern”) Jews from North Africa and the Middle East, including Iran.

Because they were separated from Northern European, or Ashkenazi, Jews for so many centuries, Sephardim developed their own liturgy and customs. Ashkenazi families were long the dominant Jewish group in the U.S., arriving like so many other immigrants from England, France, Germany, Russia and Eastern Europe.

Sephardic students are a large presence at Shalhevet and have grown up with unique sets of customs. According to a Boiling Point poll, nearly half of the students — 81 out of 166 — are Sephardic.

“I don’t think it defines me as being Jewish but it’s the same sort of pride that’s been maintained through generations,” said freshman Liat Menna, whose father’s family is from Iraq. “That’s what’s so important about it – the tradition aspect. Being able to be proud of it and being more comfortable.”

Their unique customs range from the halachic — like eating kitnyot, rice and corn products on Passover – to the culinary, involving their favorite dishes. But also among them are several key differences in davening. Students lain with Sephardic trope, they do not stand for Kaddish, and they perform brikhat cohanim, the priestly blessings, every day.

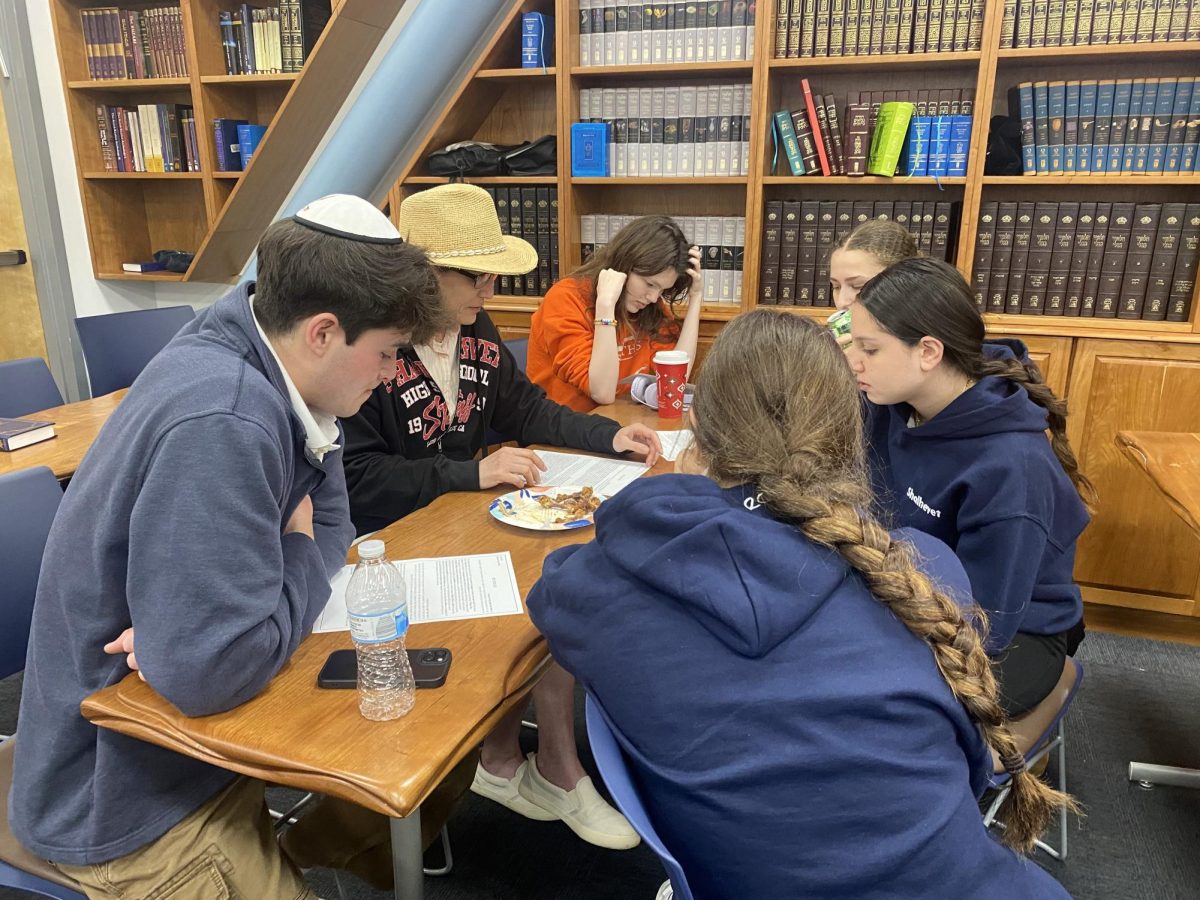

But until Nov. 3 this year, all students davened in either the upperclass or lowerclass Ashkenazic minyans, or in previous years, alternative minyans like the Happy Minyan or the Yoga Minyan. The student-pushed process to create a Sephardic minyan took weeks of discussion and proposals, particularly over whether girls would be allowed to carry the Torah.

When it was finally formed, for its first two weeks the minyan davened in the lunch room, eventually moving because of distractions from students coming to the cafeteria for breakfast after davening.

“Now we have it and go every day to davening,” said junior Ronny Shemtov, whose family is from Iran. He added with a smile that he was one of the people who had pushed for the minyan.

“It’s very important to me,” Rony said. “My family is Sephardic and I want to pray Sephardic. We don’t say ‘se,’ we say ‘te.’ Since I saw there was a chance to have a minyan, we took it.”

On a typical morning, chattering students make their way down to the minyan’s new home, across from the gym in the basement. A mechitzah made by the school of construction paper separates the 15 boys from 11 girls. The minyan is advised by Judaic Studies teacher Mr. Jason Feld, its only Ashkenazi member, who said he loves the minyan and calls himself “an invited guest.”

“We have a substantial Sephardic population in Shalhevet,” said Mr. Feld. “We don’t do enough celebrating their traditions. The fact that we do have a Sephardic minyan I applaud.”

A wall between two classrooms was torn down in order to create more space for the minyan, and sophomore Maya Ben-Shushan, who has family from Morocco, plans to paint the walls to liven up the room. Tacked to the otherwise bare white walls is a shriti,* a text from Kabbalah common in Sephardi homes/shuls.

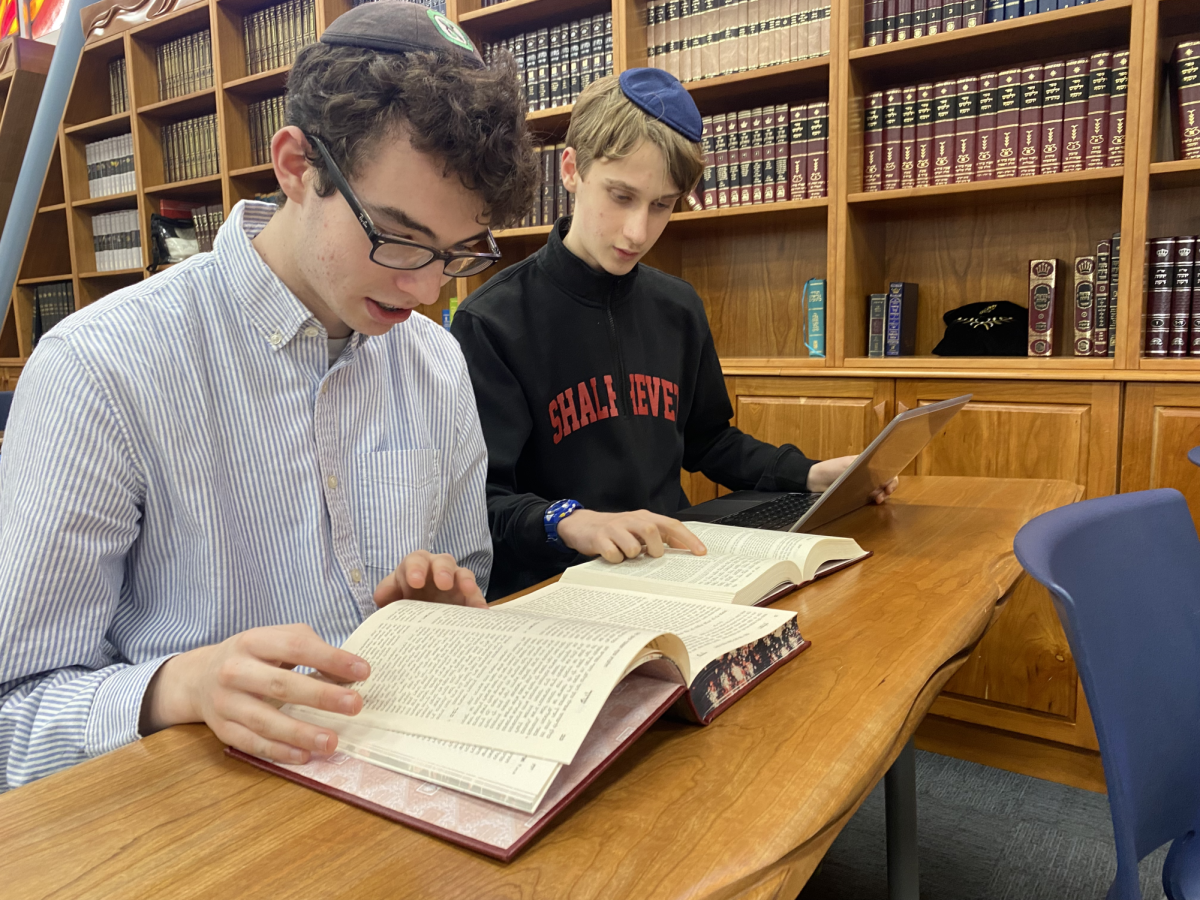

Most of the boys use Sephardi siddurs, which they bring from home because the school doesn’t have any. Unlike in an Ashkenazi minyan, the chazzan recites all prayers aloud in a fast-paced chant.

“It goes fast but we don’t skip over anything,” said Liat.

However, some Sephardic students don’t join the minyan despite their heritage.

“They go too fast and I can’t keep up,” said sophomore Sarah Soroudi, whose family is from Iran. “At this point I don’t really care about the style if it’s preventing me from praying.”

“I enjoy the Ashkenazi minyan because there’s more singing and it’s less strict,” said sophomore Jillian Einalhori, whose family is also Iranian.

The Sepahrdic minyan also finishes a few minutes later than the Ashkenazic minyan, a deciding factor for some students.

“I’d rather be in the Sephardic minyan but the Ashkenaz minyan is shorter,” said freshman Adam Rokah, whose father is Israeli and has grandparents from Libya.

Sephardic students who went to Maimonides Academy, one of Shalhevet’s feeder schools, became used to the Sephardic davening there and were uncomfortable in Shalhevet’s Ashkenazic minyans.

“I grew up davening Sephardic,” said David Rokah, the only senior in the minyan and brother of Adam Rokah. “Switching over to high school was kind of a funny transition because I had all the Sephardic tunes memorized. I used to hate davening in Ashkenazic minyan where I had to stand for Kaddish.”

Ashkenazic students at Maimonides also had a tough time adjusting to that school’s Sephardic davening.

“I became used to it after about half a year, but I’ve always been more comfortable with nusach Ashkenaz,” said senior Adam Kellner.

Another difference between Shalhevet’s Ashkenazic and Sephardic minyans can be seen only on Torah-reading days, when the Torah is taken directly to the bima by the chazzan instead of being paraded through each section – typical for Sephardic synagogues – instead of being carried by boys and girls through their respective sections.

Senior Leah Katz, who had been active in supporting girls’ desire to carry the scroll in the upperclassmen’s minyan, says that “it’s a relief” not having to worry about the issue now. Leah is descended from Turkish Jews on her father’s side, and thinks that as a holy object, it should not be paraded around, but if it’s being passed through one side of the mechitzah, it should be carried through the other as well.

Usually, juniors JoJo Fallas, Ronny Shemtov and Jordan Banafsheha take turns leading the service, but they are looking for new chazanim. In the freshman-sophomore Ashkenaz minyan different people lead the service every day, while the same few people lead usually lead the junior-senior Ashkenaz minyan.

“It’s been a great start and there’s room for improvement,” said Jordan, whose family is from Iran. He said they plan to teach the service to students who want to learn, but people can also learn just by sitting in the minyan every day.

“There are challenges in terms of cultural literacy,” Mr. Feld said. “You have to be able to read the whole tefilah well [to lead the service].”

Although there’s light chatting on the girls’ side, there’s agreement that they love the minyan.

“I go to a Sephardic shul, and so I love that I can daven the same way in and out of school,” said sophomore Natalie Dahan. “I thought I would always have to pray in school the Ashkenaz way, but it’s cool that now I don’t.”

VIDEO: Two problems solved at once as Sephardic minyan debuts 11/10/2011

Related: About 50 students attend school’s first Sephardic minyan 11/7/2011

EDITORIAL: On women and Torah, Shalhevet should lead 11/4/2011

Related: Shalhevet stands alone among Orthodox schools in letting girls carry Torah, survey finds 11/3/2011

Related: Tradition may rule, but law says girls may carry the Torah (11/3/2011)

Related: Rabbi Segal okays first Sephardic minyan; no changes to Ashkenazic minyans 10/31/2011

Related: Meeting yesterday began process of minyan decisions, Rabbi Segal says 10-26-2011

Related: Girls will no longer carry Torah at junior-senior minyan 10/7/2011