Getting paid on Shabbat: The work is fun, but is it legal?

Every shul does it, but how does being paid for childcare and other tasks square with the Fourth Commandment

On a typical Shabbat morning in a typical synagogue in Los Angeles, dozens of small children are chatting and giggling, playing with toys and drinking apple juice. They stop to sing a teenage-led Shacharit, and after several hours are picked up by their parents. With them are mostly religious high schoolers, who care for the babies, toddlers, children and pre-teenagers of shul-going parents throughout the country.

For many Jewish teens, working in synagogue childcare is the first regular job — and paycheck — of their lives. But working on Shabbat is directly prohibited in the Ten Commandments, in Shemot chapter 20, verses 8 to 9: Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord your God. In it you shall do no work.

How is this possible? Teenagers who work at shul, in child care and other positions including laining (chanting the words of the Torah) and leading davening, are almost always paid as employees, which seemingly violates the prohibition.

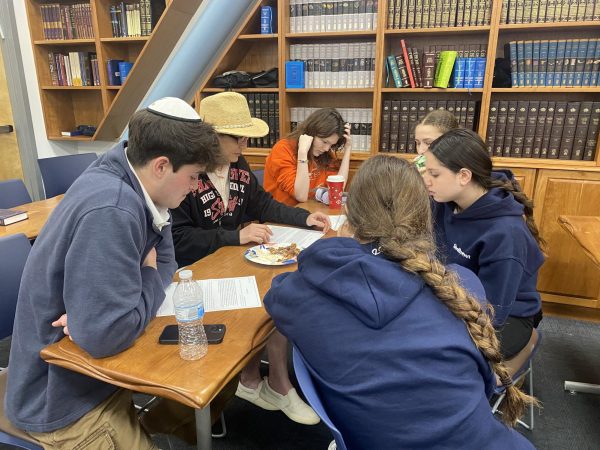

Students interviewed by the Boiling Point said working positively impacts their Shabbat experience. But most weren’t sure about the halakhic implications.

“Because I work, I actually go to shul — I have a chance to daven and just be with the kids and socialize at shul on Shabbat,” said senior Amir Maman, who has been a youth group counselor for four-plus years at Beth Jacob Congregation in Beverly Hills.

“Halachically I have no idea if it’s okay — I ask myself the same question,” he said. “But I just think it’s better than me sleeping until lunch.”

Junior Ari Schlacht, who works at B’nai David-Judea, said he didn’t think there was anything wrong with being paid on Shabbat.

“If halacha goes against it, then I’ll stop right away,” said Ari. “But as far as I can tell, there’s nothing that says we shouldn’t be getting paid on Shabbat.”

In reality, it’s complicated. The actual halachic justification — not only for child care workers but for rabbis, teachers and others — relates to exactly what Amir and Zach described.

Rabbi David Block, Assistant Principal for Judaic Studies, said working on Shabbat is a complex issue, but halachically acceptable if it involves working for a shul.

“There is an issue with it,” Rabbi Block said, “because in theory one should not be making money on Shabbat.”

The issue, he said, is called schar Shabbat,” schar meaning payment. Rabbi Block said there is a general prohibition against doing business on Shabbat, stemming from the prohibition against writing — in Hebrew, kotev.

“Writing, or confirmation of a deal, is such an essential part of business,” he said.

Schar Shabbat, Rabbi Block explained, is the prohibition against being paid for work which is technically permissible on Shabbat. For example, taking care of children does not violate the laws of Shabbat, but because of schar Shabbat, it would be forbidden to be paid for doing so.

But Rabbi Block explained two ways to potentially override schar Shabbat. One is schar Shabbat behavla’ah, which in Hebrew means being paid on Shabbat for something that is mixed, from the Hebrew word balah, to absorb. A Talmudic concept found in the Shulchan Aruch, the Jewish legal code, this principle permits compensation for work done on Shabbat as long as it is mixed with, or “absorbed into” work done on weekdays — in other words, for work that is is only partly done on Shabbat.

He said schar Shabbat behavla’ah is simple when it comes to being paid to lain or lead prayers, because those who do it must practice during the week to prepare for these roles. However, children’s group leaders in synagogues work only on Shabbat.

“So this is hard,” Rabbi Block said. “But the way some shuls go about trying to solve it is by having meetings during the week. Then the shuls are paying both for the meetings and for working on Shabbat.”

The second override, according to Rabbi Block, comes from a rishon, one of the prominent rabbis who lived during the 11th to 15th centuries. The rishon known as the Mordechai — Mordechai Ben Hillel haCohen — stated because schar Shabbat is a prohibition not explicitly stated in the Torah but developed by the rabbis of the Talmud, pay is permitted if the work is done in order to fulfill a mitzvah. Work for the purpose of the mitzvah, the Mordechai said, that was not included in the schar Shabbat decree in the Talmud.

‘“You can say that being in shul and allowing parents to daven in shul while you’re taking care of their kids, especially if what you’re doing with the kids is also religiously valuable, might be included in a mitzvah,” Rabbi Block said.

Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Yagil Tsaidi, who runs the Teen Minyan at Beth Jacob Congregation, offered a third reason that paid Shabbat-related work could be permissible.

“Halacha acknowledges the necessities that a community will need to enhance Shabbat,” Rabbi Tsaidi explained, “and that a shul will need a rabbi and babysitters for their youth groups and a chazzan and a Ba’al Koreh in order to make the place function.”

“Creating an atmosphere in which high school kids come to shul on Shabbat and we daven and we eat together and we say brachas and we learn, I think that’s davka” — especially or exactly — “the idea of Shabbat,” Rabbi Tsaidi said. “That is the spirit of Shabbat, and if that weren’t happening, it would be ruining the spirit of Shabbat.”

He also mentioned the halachic obligation of kivud v’ oneg — meaning to respect and enjoy Shabbat, which gives halachic validity to work that preserves the Shabbat spirit. He said that working at shul on Shabbat actually promotes the spirit of Shabbat.

Rabbi Block agreed, saying kivud v’oneg is part of the mitzvah of Sabbath observance.

Shalhevet junior Zach Helfand, who works at B’nai David, said that working on Shabbat is clearly necessary for the community.

“It’s just what’s necessary,” Zach said. “You have to have these kids groups, and no one would do it for free. Whether it’s good or bad isn’t really a question, it’s more of just what is.”

Senior Noa Kligfeld said that enhancing others’ Shabbat experiences is part of what motivates her to work, even if it means sometimes sacrificing her own davening.

“I won’t do it every weekend,” Noa said. “But some Shabbatot I’ll say I’m not gonna have a davening experience, so that someone else can have a davening experience, and I think that’s really important.”

Freshman Marlee Drazin has been working at B’nai David Judea since the beginning of this year. She has never asked a rabbi whether it’s okay, but enjoys it so it doesn’t feel like work to her.

“I’m not being forced to do it and I really do enjoy working with kids,” Marlee said.

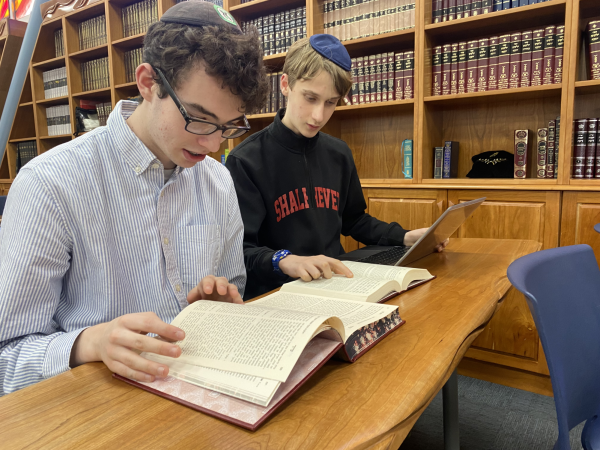

Schar Shabbat behavla’ah, according to Rabbi Tsaidi, also permits him to work on Shabbat.

“What the shul will pay me for on the books is for all the practice I do outside of shul during the week,” Rabbi Tsaidi said. “Or they’re paying me for everything I’m doing including on Shabbat.

“I make a drasha,” or short sermon, he said. “I practice. I learn what I’m gonna speak about. I recruit the kids who are going to come to minyan.”

Rabbi Tsaidi and Rabbi Block are both fathers of young children, so it’s easy to see how having childcare at shul improves their observance of Shabbat. It also sets up good habits for the teens — who like Amir, might otherwise just sleep in on Shabbat mornings but instead are now used to getting up early and going to the synagogue.

“Making it more attractive for kids to come to shul on Shabbat is kind of what we’re aiming for here,” Rabbi Tsaidi said. “Spending every Shabbat with a Shalhevet kid, with a YULA kid, with everyone who comes to Beth Jacob teens, kind of makes my Shabbat. It definitely enhances it and makes it very wholesome and uplifting and spiritual.”

Rabbi Block said that while these permissions may seem to be loopholes, he views working at shul on Shabbat as a positive thing, so they are legitimate.

“There are certain times that we have loopholes in Judaism and it won’t always feel so good,” Rabbi Block said. “But I think this is one of those cases where it’s not de’orayta” — meaning from the Torah itself — “and there are other things to rely on… the schar Shabbat behavla’ah, and that it may be a mitzvah, and that it’s a potential benefit, which is that you’re bringing people to shul on Shabbat.

“This all comes together to feel to me that it’s not really a loophole but a very beautiful practice,” he said.

Torah Editor Nicholas Fields, Community Editor Jacob Joseph Lefkowitz Brooks and Features Editor Tobey Lee contributed to this story.

Get the latest from The Boiling Point. Sign up for our news feed.

Lucy Fried was co-editor-in-chief during the 2018-19 school year and went on to study at the Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. She is now a junior at UC Berkeley.