For COVID-19 nurses on opposite sides of the world, keeping families away is the hardest part

Two nurses, one in New York and one in Jerusalem, say new roles, long hours and suiting up from head to toe are all part of the job

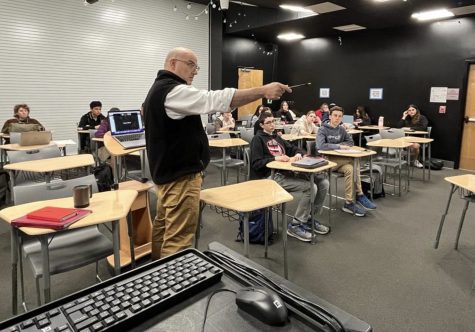

Photo Courtesy of Sydney Miller

STRONG: Sydney Miller ’13 is ready for her shift at NYU-Lagone Hospital’s coronavirus unit April 20.

Shalhevet alumna Sydney Miller ‘13 is a nurse at the NYU Langone Hospital in New York. Typically, she finds enjoyment in sitting next to an anxious patient and comforting him or her through conversation. However, due to COVID-19, she now mainly communicates with patients on the screen of an iPad, or through the glass doors of the ICU.

Halfway around the world, Chava Gardner, 44, is a nurse at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem. She stands and watches as one more elderly COVID-19 patient passes away without family by the bedside. Her N95 mask once again becomes stained with tears.

Sydney Miller and Chava Gardner are on opposite sides of the planet — and yet, in the very same place.

Both women’s professional lives as frontline healthcare workers were upended this spring by the novel coronavirus and the disease that it causes, COVID-19. Chava, with 17 years of experience as a surgical nurse, normally heads a Hadassah pre-op unit but now has been working in the corona ward. Sydney is barely out of nursing school at NYU and has only been a staff nurse for nine months.

But both women are determined to save as many lives as possible. Their professions do not allow them to work from home through Zoom. As nurses, each has put her own life in jeopardy by working in close proximity to Covid-19 patients day in and day out.

While they face some different challenges, their shared experiences as nurses in corona wards seem to outweigh any differences dictated by the countries and healthcare systems they work in.

Sydney grew up in Beverlywood with four siblings, including current freshman Zoe Miller, her youngest sister. After graduating from Shalhevet, Sydney headed to Brandeis University to get a degree in business.

But she realized in her senior year that her true calling was nursing. She transferred to NYU’s accelerated nursing program and graduated last spring.

In September she started as a staff nurse at NYU, expecting to encounter various diseases throughout her career. But COVID-19 was not one of them — it didn’t yet exist.

Seven months later she was being fitted for an N95 mask in the ICU. Sydney said her unit was the first at NYU to be designated for coronavirus.

“Things changed so quickly with this disease,” Sydney said in an interview last month. “Soon the whole hospital was filled with COVID patients.”

In March, Sydney was ICU-trained and taught how to suit up from head to toe in gloves, mask, gown and face shield — every day. That protective gear, she said, is a necessary part of her arsenal in the fight to heal patients with COVID-19.

She said she feels supported by her hospital being provided with fresh Protective Personal Equipment, also known as PPEs, whenever she needs it — knowing that many other hospitals around the U.S. and the world have not been able to do the same for their staffs.

But putting on, wearing, and then taking off PPE gear is not the most difficult safety precaution, she said. The harder problem, she said, is physical distancing — not from other staff but from infected patients.

“When we go in a patient’s room, we have this feeling of having to get out as quickly as we can,” said Sydney in an interview last month. “But I hate it. I don’t like that feeling.”

As a student and in her first year on staff, she could sit down with a patient and try to distract them from their illness, or just get to know them as a person.

“I’m so used to being able to sit down with a patient and have a conversation to make them feel a little bit better,” she said. “[This] has been the hardest for me to handle.”

NYU Langone Hospital has tried to give COVID-19 patients support and attention in other ways, she said. For example, the hospital staff provides iPads for all COVID-19 patients, for communication with family members or hospital staff.

“It comes down to the little things we can do,” Sydney said. “One of my colleagues had a patient whose birthday was at midnight, so we all got together and wrote a card… and stood by the glass doors [of the ICU], singing happy birthday.”

According to Sydney, these are the gestures that make a big difference for her patients.

The big difference has been made by her co-workers. She normally has two roommates, but is currently living alone as they both went to stay with their families when the pandemic hit.

“I would not be able to do it without my incredible support system of co-workers,” Sydney said. They lift one another up, she said, and are “always also there for a little bit of comic relief, just to help us get through this time. I would not be able to do it without them.”

On the other side of the world, Chava Gardner has also faced many struggles while caring for COVID-19 patients, finding it difficult to ask patients’ families to stay away.

“I was treating very old people who were there on their own, and they were either Holocaust survivors or have been through wars,” Chava told the Boiling Point in May.

“They have marvelous and huge families, but none of them were allowed to go in there,” she said. “It was the hardest and saddest thing seeing these people die without their family around them… It was just a very, very rough experience.”

Chava usually heads the pre-operative unit of Hadassah’s nursing department, but when the first of five corona units were opened at Hadassah, she quickly volunteered to work there.

“The experience itself, some of it I’m telling you was very difficult,” she told the Boiling Point in May.

But she was proud of her hospital’s response.

“Some of the things that we’ve done were amazing,” Chava said. These included helping older patients Facetime with their families and even, in some cases, letting family members suit up in PPEs.

“[Then they could] go in to say goodbye in person when we knew one of the patients was dying,” said Chava. “This way they weren’t totally on their own.”

That didn’t make it less emotional for Chava, however.

“There were tears mixed up with my mask and my faceguard and there are just tears everywhere and that was a very special moment,” Chava said. “It was very emotional.”

Chava lives with her husband and four children in a neighborhood called Baka which is located in Jerusalem.

“Working in the corona ward, my schedule has completely changed,” Chava said. She now works on weekends in addition to weekdays, her hours jumping from 40 to 60 a week.

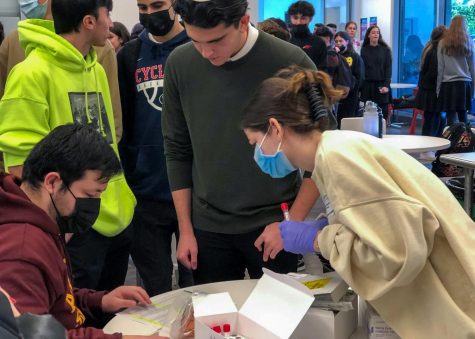

In hospitals, staff testing is key in controlling the spread of the virus. Hadassah Hospital, fortunately, has the means to test all staff members every two weeks, thereby giving them and their families peace of mind.

Conversely, NYU Langone Hospital only tests staff when they are exhibiting signs of illness or are being transferred to another unit in the hospital.

Chava said when staff members in her ward were first tested, it was discovered that 30 healthcare workers had contracted the virus, despite being asymptomatic.

“Despite coming into contact with COVID-19 patients daily,” Chava explained that she feels completely safe, health-wise, coming home to her family every night because she is regularly tested.

She reported that her children feel more confident about her working with these patients, “because they knew that I was negative constantly. That means the hospital knew what they were doing, I knew what I was doing, and it was safe for me to come home.”

According to the World Health Organization, as of June 22, 306 Israelis and 30,927 New Yorkers had lost their lives to the novel coronavirus. Israel and New York City have similar populations: Israel has 8.6 million according to Worldometer, and New York City itself currently has 8.4 million, according to the New York City Planning and Population Division.

Neither Chava nor Sydney was actively working in a COVID-19 unit the third week in June. The number of cases had dropped in both Israel and New York.

Chava said she was trying to segway back into “regular life,” while still testing patients and healthcare workers for coronavirus every morning.

For Sydney, last week was her first working in a non-COVID-19 unit since March.

“I may be temporarily sent back to a COVID floor,” Sydney said.

But neither woman has had second thoughts about her chosen career.

“I love being a nurse, I thank God every day that I chose this for my career and I’m a nurse,” said Chava. “Because I love it — not because I’m a hero and not because I’m an angel, and not because I’m this wonderful person.”

No one knows how long it will take to discover a vaccine, or for the coronavirus to disappear.

“It’s just a very scary time and I have my good days and my bad days,” said Sydney in May. “I try to remind myself as scary as it is now, we will get through this. It’s hard to see the end but we will.”

Juliet Wiener,12th grade, joined the Boiling Point her sophomore year as a staff writer, and covered science, particularly on Covid-19, as the paper’s science writer in her junior year. During her senior year, she is now the Boiling Point’s Outside News Editor. Aside from journalism, Juliet enjoys being a witness on Shalhevet’s Mock Trial team, going to the beach, and drawing.