What’s in a pseudonym?

There are lots of reasons to disguise your online identity, but whether it works is an open question.

November 20, 2013

Melissa transformed into Mah Lissa. Natalie rechristened herself Nah Tally, and Kaili became Kay Lee…in cyberspace, that is.

With college application season heating up, seniors have begun changing their names on Facebook, continuing a trend that has become a rite of passage in the past few years.

Students say they change their names to protect their online identity from potential searches by college admissions officers, when one inappropriate post or picture could prevent them from being admitted.

“I changed my name for colleges,” said senior Joelle Edison, who shortened her Facebook name to Joelle Ed, cutting out the ‘ison’. “I don’t mind showing them what I do, but I just wanted to have some sort of privacy. And I also changed it because all my friends are changing theirs and it’s fun.”

A 2012 survey of 350 college admissions officers across the country conducted by the educational company Kaplan found that 26 percent of schools actively look up applicants on Facebook, and 27 percent search on Google. Thirty-five percent said these searches elicited a negative view of the applicant, citing photos of alcohol consumption and essay plagiarism as examples.

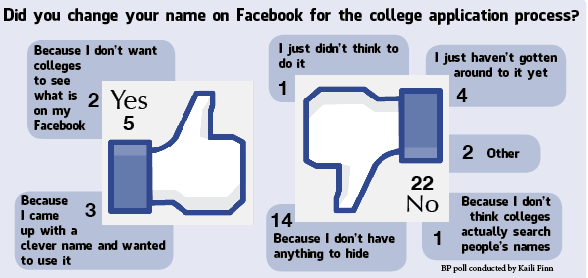

Shalhevet seniors have apparently gotten the message. Five of 27 who answered a Boiling Point poll during Advisory last month said they had created a Facebook alias, most to hide their profiles from colleges, and another five said they planned to but hadn’t thought of it or gotten around to it yet.

On the other hand, 14 out of the 27 say they’ll keep their names as is, saying they didn’t think their Facebook pages held anything a college would mind.

“I don’t feel like I have anything to hide,” said senior Matthew Denitz. “If anything, my Facebook is going to show them the type of kid I am and hopefully promote colleges accepting me.”

But seniors who attempt to conceal their cyber-identity might want to know that they it doesn’t necessarily work. According to Internet expert Lori Getz, who founded Cyber Education Consultants and regularly speaks to groups about Internet safety, changing your name on Facebook will not prevent people from being able to find your account, or from finding out more about you.

“Most teenagers don’t understand how all of this works in the first place,” Mrs. Getz said in an interview. “They’re incredibly savvy when it comes to using technology, but don’t understand the data mining process.”

Everything you say and do, she said, is collected on the Internet — not just what you post with the public in mind.

“It shows a profile about who you are and what you like,” she said. “So people try to change their names thinking everything they have done will be deleted, and that’s not the case at all.”

In recent months, troves of information released by Edward Snowden have showed that the online communications even of world leaders are not secure. And a Nov. 10 New York Times article said college admissions officers are even viewing students’ Twitter posts.

Getz said there are websites that link e-mail addresses with social media sites—so if a senior uses the same e-mail account for the Common App as for Facebook, an admissions officer can find their page regardless of whether they changed their name.

For example, a site called spokeo.com, she said, compiles information from social media, the White Pages of telephone companies, and public records in order to sell e-mail addresses, house addresses and even the dollar value of a person’s home.

Meanwhile, although not all admissions officers may be actively searching for prospective students online, there are others involved in the process who may be doing so, such as alumni recruiters who conduct interviews with prospective students.

“Recruiters who come to schools and interview students are the ones who are looking online,” Mrs. Getz said. “They want to have a basic understanding of who the student is before the interview. They’re looking much more than the admissions counselors.”

Mrs. Getz’s advice to college applicants is simple.

“Clean up your Facebook,” she said. “Leave your name there so if a recruiter wants to look at you they’ll see all the fab things you’ve done — just clean it up first. It’s still out there but its much harder to find, and they really just don’t want to find stuff that’s going to embarrass the university.”

Shalhevet seniors may be the ones most concerned with their online personas this season, but it’s not just Facebook and Twitter that can be embarrassing—and public—as freshman Maayan Waldman found out in October.

In a journalism workshop, Boiling Point advisor Mrs. Joelle Keene had students Google themselves to see what came up. For some, it brought up a slew of old embarrassing posts and photographs—things they didn’t even know still existed.

Maayan discovered AIM Instant Messenger statuses from when she was in 6th grade, and pictures from a contest with friends over who could embarrass the other the most.

“When I was making those statuses, I thought only my friends on AIM could see it,” said Maayan, who was 11 at the time. “It was a little crazy to find out that so many people could have access to what I thought was personal information. But now I know that anyone with access to internet could see them.”

The discovery reminded her to stay diligent about her online presence.

“I think it made me realize that yes, there are a lot of ways to access things,” Maayan said. “There’s just so much people can find out about you even if you don’t know it.”

There is, of course, the 74 percent of schools that do not pursue this information. Students who create aliases do so because they don’t know which of their schools do or do not.

Margaret Lucas, Associate Director for Undergraduate Admissions at New York University, said NYU is a part of that majority that doesn’t routinely search – yet even she finds herself using this information.

“A fair number of universities don’t actively seek out that information,” said Ms. Lucas in a telephone interview. “It’s more that if anything comes to our attention, then we would look at it, so the changing of the name doesn’t necessarily change the information that we see.”

Sometimes, it seems, they don’t have to search.

“Other people have brought to our attention something that students have been posting,” Ms. Lucas said. “We take all of those with a grain of salt and rarely do we take action, but if we were to see anything inappropriate posted, especially on an NYU-affiliated page, we would take action.”

When she does see applicants’ electronic malapropisms, she said, it’s often because their Facebook “friends” have sent them to her attention.

“I am not sure if it’s the competition of the college admissions process or an unfortunate nature of bullying or competition, but we do receive a handful every year of anonymous print-outs of Facebook pages,” said Ms. Lucas.

“It’s unfortunate that it happens, but students should be aware of who they are friends with because more often than not people send us things from their friends Facebook pages that may be inappropriate.”

Ms. Aviva Walls, Shalhevet’s Director of College Counseling and Academic Guidance, worked as an admissions officer for both Barnard College and NYU.

“I never actively looked up a student,” said Ms. Walls, “but I did alert my bosses to a student who created a Facebook page for his NYU class and was writing about all the drugs they were going to do during orientaton.”

Whether or not college applicants need to worry about being searched for by admissions officers, they should be cautious of what they post in any case, said Ms. Walls. As a rule of thumb, she tells students: “Do not post anything that you wouldn’t want announced on the bima at synagogue.”

“It can affect how you get a job, and people’s opinions of you,” she said. “You have to be smart about how you use social media.

“Changing your name isn’t going to work forever.”

While many students change their names to hide them from internet searches, others do it for fun. There is also an element of creativity involved — new names are often puns or homonyms of their actual names.

Shalhevet alumus Danny Silberstein ’13 changed his name to Dan Knee last fall, then changed it back to his real name after he’d been accepted to Berklee College of Music in Boston – his first-choice school.

Senior Jennie Drazin doesn’t plan on changing her name unless she comes up with something clever.

“It’s almost like a milestone or coming of age thing,” she said. “It’s a rite of passage in that it identifies you as a senior, and that you are in the midst of this big process. You’ve reached this point where you don’t take things so seriously. It’s just fun.”

She said loves seeing the mysterious pseudonyms pop up on her newsfeed.

“It’s fun to figure out who people are,” said Jennie.

And that’s exactly what the admissions officers are trying to do as well.

This story won a 2014 Gold Circle Award Certificate of Merit in the General Feature category from the Columbia Scholastic Press Association, and a National Award for Feature Writing in the 2014 International Writing and Photo Contest of the Quill and Scroll Society, judged by the American Society of News Editors.