SENIOR POLAND-ISRAEL BLOG / Post 3: A cable car of ghosts

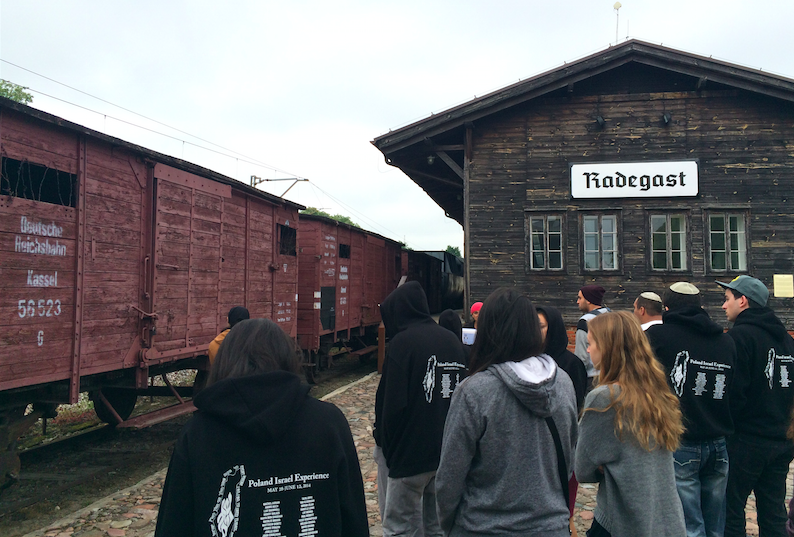

TRACKS: Seniors prepared to board train cars that were used to transport victims from the Lodz ghetto to Chelmno and Auschwitz death camps.

May 31, 2014

By Liat Menna, 12th Grade

LODZ, Poland, May 31 — My name is Chaya. I never really thought about it much before today. Chaya means life — more specifically, living. I am living.

In the ghetto some people say they were living. Yes, they were breathing.Yes, they were working. No, I do not believe they were living. To say that the ghetto was life angers me. Because it was not. Just because it was relatively better than the camps doesn’t mean it was good. It wasn’t a life of living. It was a life of surviving.

The ghetto was the last of any remnant of anything minutely identifiable as life. It was the last time family existed. Once someone left those walls, they were alone. They were a lonely heartbeat. A heartbeat that did not beat for life but beat to prolong a death.

At the Radagest station in Lodz, we sat in one of the train cars. There was a moment there when I felt like a ghost. I felt as if everyone in that car was a stranger. They were worlds I did not know. Then, it hit me. These worlds could have been the lost worlds. Maybe they were, but even if they were not it was worlds just like them that sat in the torment of these cable cars.

We began to sing “Ani Ma’amin” — “I believe with perfect faith…” The words right now make little sense to me. Yet there is some unspeakable power and spirit in them. These words meant something to some of these victims. For that reason, I sang with dignity. I felt like the more I sang the more voice I gave their spirit.

When we were told to leave the cart, it was very difficult for me. I felt that I left my family there. I wanted to wait for them. I hoped they would come.

But they didn’t. They couldn’t.

Once out of the cart, our screams from the hymn of “Am Yisrael Chai” vibrated through my head. I felt a huge weight. The weight of my name. I am Chaya, and Yisrael is Chai. My living is part of their living. My living is the living of Yisrael.

WOBRUM FOREST: The Shabbats They Lost

By Liat Bainvoll, 12th Grade

WOLBRUM, POLAND, May 30 — Today we went to the Wolbrom forest, where the father of Mr. David Shapell — a major donor to our Poland-Israel trip — is buried. Mr. Shapell’s father and hundreds of other Jewish men, women, and children from the shtetl of Wolbrom are all buried in three mass graves. They were left to die, sold out by their neighbors, and desecrated once the bodies were cold.

At the grave, my group with Benny and Natalie sang a rendition of “Esa Enai,” followed by a poem written by Benny about the irony of the green and flourishing grass masking the bodies of hundreds. Then, we gave the people buried there something that they haven’t had in 74 years. We welcomed the Shabbat with them.

We started with “Shalom Aleichem.” This hit close to home with me because my family instituted singing it as a tradition every Friday night at the Shabbat table after my grandfather passed away. A Holocaust survivor from Lodz, he was full of life. There is not one moment that I remember him without a smile, unless it was part of a joke. This life that he had, is the life that all those souls were stripped of.

We gave them one more opportunity to bring in Shabbat and the joy that comes with it.

After this experience, I will never again see my family tradition of singing “Shalom Aleichem” as a nuisance. I will not mumble the words annoyed, but it will sing with pride and full of life for those who never got the chance to sing.

PARIS: ANTICIPATION

By Tamar Willis, Editor-in-Chief

PARIS, May 29 – Arriving late from Los Angeles, we missed our connecting flight to Warsaw and are stuck in the Paris airport for six hours. Half the group boarded a flight three hours later and the rest of us are still here, waiting. We’ll probably miss the opportunity to see the Warsaw cemetery and remnants of the Jewish ghetto, which irks some of us but there’s nothing we can do.

The extra time gives me a little time to think about what’s to come. Honestly, I’m scared. I’ve heard from so many who have done the Poland-then-Israel thing that it is amazing, life-changing, and unlike anything they’d ever experienced. I’m sure it will affect me in ways deeper than I can anticipate and that’s unnerving. I just don’t know what to expect, and while I told myself that I wouldn’t overthink it, sitting on the carpeted airport terminal I can’t help but think about the places I’m soon to see.

Thanks to the 16-euro voucher AirFrance generously gave us to make our long wait more bearable, Jennie and I are sitting and drinking cappuccinos at an airport cafe. She tells me about her grandfather, who said he’d never come back to Eastern Europe to do the Holocaust circuit. The last time he was here, he lived in the forest with his family and only after the war discovered that his home village had been burned and destroyed. Even after our extensive Holocaust education prior to the trip, I can’t begin to fathom some of the stories I hear.

But soon I’m going to be standing in the camps where millions of Jews just like us were brutally murdered, I’m going to be seeing the forests where they hid and going to visit the houses that were taken away from them. I have no idea how I will react.

“You’re going to be pretty emotional at the camps, right?” I ask Jennie. She gives me a look that confirms my suspicion, incredulous that I would even ask.

But she doesn’t know either. No one does.

I ask Jennie how she wants to be comforted when crying. Should I hug her, talk to her, try to cheer her up? I ask myself the same question and decide that I think the best thing for me would be to be with people but not to talk about it.

“I don’t really know,” Jennie says.

As she answers, I realize the questions are probably futile anyway. It’s just not possible to anticipate how anyone is going to react, or what kind of comfort we will seek, if we seek any at all.

Now I’m back at square one. Despite trying to prepare myself for what’s to come, I can’t. My nerves aren’t quelled–the caffeine from my cappuccino has only excited the butterflies more. I guess it’s just better not to think about it.