October 19, 2012 – 3 Cheshvan 5773

Parshat Noach

Dear Shalhevet Community,I am excited to write once again to discuss the religious philosophy of the school and how it informs the decisions and choices unique to a Modern Orthodox educational institution.

By way of background, I received the following email from a very supportive Shalhevet parent:

Rabbi Segal:

First, I love your weekly updates that provide us parents (and others) insight into what is going on in the school.

I wanted to share my thoughts with regard to the issue of whether Shalhevet would allow its students to attend the newspaper award ceremony on Shabbat in San Antonio. I understand what decision was ultimately made, and the Boiling Point article gave a lot more detail on the decision and the school’s consultation with halachic authorities. My question/concern is why was there a debate/question in the first place?

I know these types of decisions come up all the time for us Modern Orthodox Jews as individuals, and we “bend the rules” as individuals at times. However, as an Orthodox Jewish institution, I have to say I was surprised there was even an issue/debate. Last year, everyone took such pride in Beren Academy not playing basketball on Shabbat in the state tournament. I have read in the past how the Shalhevet Model UN team does not participate on Shabbat and yet does so well. Why should this be any different? What message are we sending our kids? Does it depend on the event that the school will decide whether it is appropriate to attend on Shabbat? Your e-mail did not address these issues — why it was even being considered to allow the students to attend on Shabbat. One prospective parent commented to me this past Shabbat that they were very surprised it was even an issue. They said that when they met with you as a prospective parent, you stated that you wanted to make Shlahavet be known as an Orthodox school that is open minded, rather than an open minded school that happens to be Orthodox. They were questioning that statement based on this issue.

You may want to consider a follow-up e-mail to explain why whether to allow the students to attend the award ceremony on Shabbat was even an issue considered by the school. What differentiates it from a sports team competing on Shabbat (which we all got the impression last year would not even be a question); and what types of events is it ok for Shalhevet to consider having its students participate on Shabbat. (I know I am interested to understand the thought process.)

I hope this feedback is helpful.

[Signature]

Wow. Where do I begin? Permit me to share my overarching philosophy on halakhah and education, and hopefully shed some light on this particular issue as well as another important topic.

I think my overall vision can best be synopsized in a comment by Rabbi Yicheiel Yaakov Weinberg (the Seridei Eish) who wrote in 1963: “It cannot be that only those who are afraid will decide the halakhah.”

I believe that we cannot automatically assume something is asur and that we need to look at each situation individually. This does not mean that we look to be meikil (lenient) in every situation. Rather, we take each question and situation on its merits and then make a decision based on all of the often unique factors involved.

I understand this can lead to people thinking I am idiosyncratic in my decision-making (Reb Noam Weissman, Director of Judaic Studies, tells me that all the time). I must say that in some ways I take it as a sincere compliment that someone would think that of me. While I would never ever compare myself to Rabbi Michael Broyde, as he is a talmid chacham of unparalleled quality and depth, I always think of him as idiosyncratic and I can never predict what he will advise me to do in a given situation. Indeed, some people would say I ruled stringently in this case and with regard to kippot, whereas I ruled leniently with regard to girls singing and to the question of performing a play during the omer. I would respond that I did not rule stringently or leniently, but instead ruled in a manner I believed to be appropriate after fully digesting all of the facts, learning through all of the sources and seeking wisdom from trusted rabbis and advisors.

Let me share with you some specifics about the thinking in this particular situation regarding the Boiling Point’s potential trip.

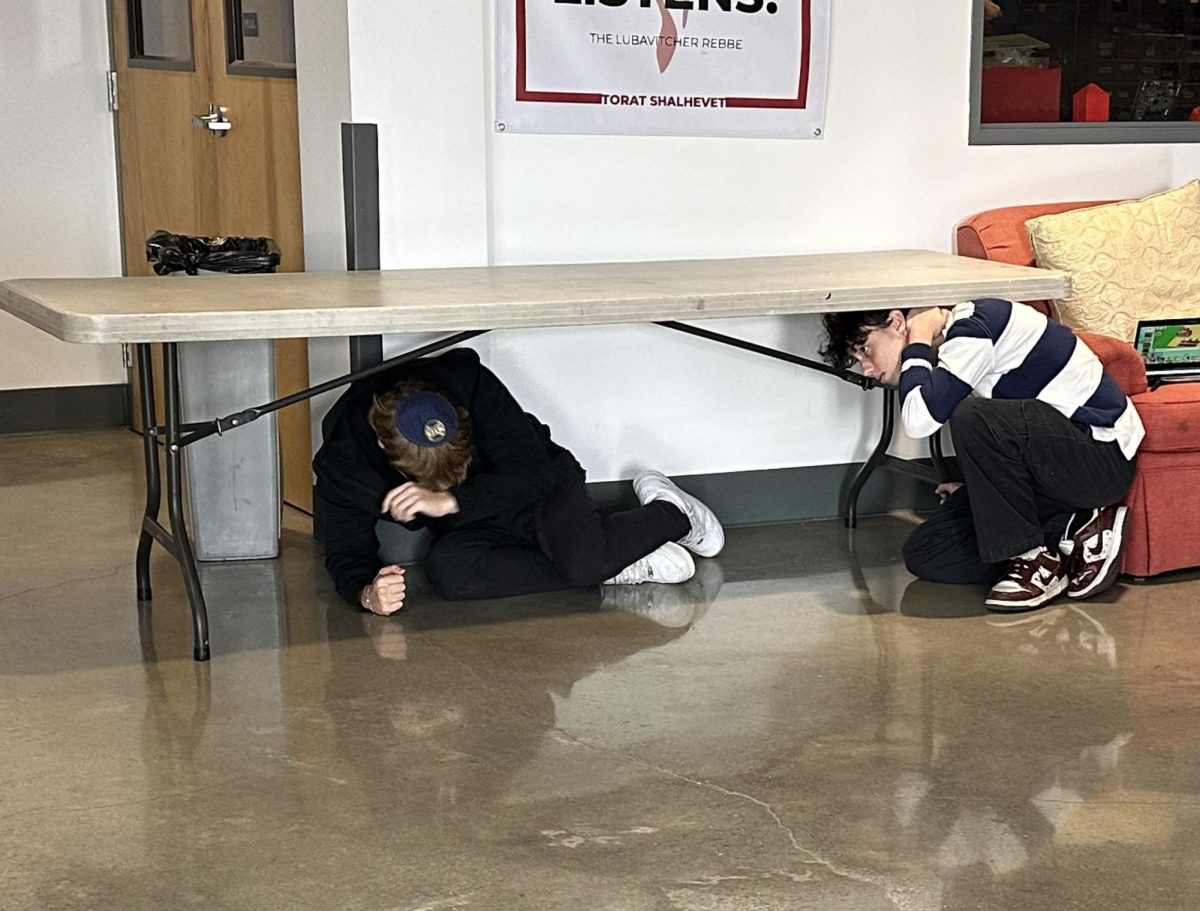

1. It goes without saying, but I will say it anyway, that our students should keep Shabbat fully – tefilah, divrei torah, zmirot, no melacha, etc.

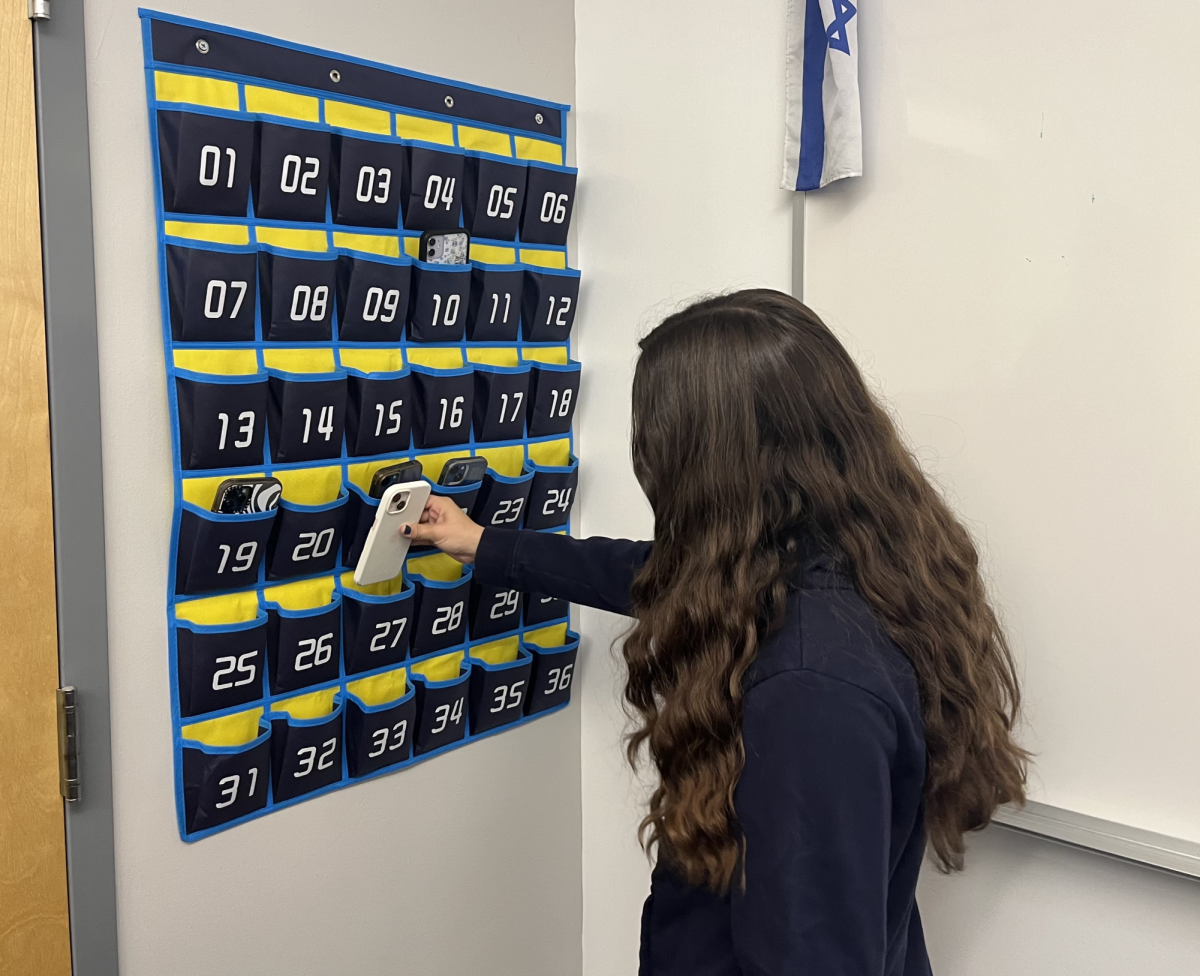

2. I saw this as a potential opportunity for a huge kiddush Hashem if our students were sitting in an award ceremony without phones and laptops, and telling and showing the other participants that they are fully keeping Shabbat, while all around them electronic bedlam lets loose. One negative ramification of the ultimate ruling is that we are foregoing that opportunity.

3. As adults living in the modern world, we should all understand and accept that our students will invariably find themselves in situations where they will be asked to participate in something on Shabbat – class, work, other. While I do hope they would politely and respectfully decline (as we ended up doing), I also see the value of teaching our students HOW to deal with this kind of situation, assuming of course all the attendant halakhot can be followed.

4. This situation differs in important ways from participation in sports or Model Congress. The key issue invoked by the potential participation on Shabbat is that it arguably transgresses ממצוא חפצך ודבר דבר. The parameters of this prohibition (which is cited in the Shulchan Aruch – Orach Hayyim, 306, 307) are not always black-and-white, and I wanted to consider seriously whether attendance at the award ceremony would cross the boundary. In short, this halakha dictates that an action can be forbidden on Shabbat notwithstanding it is not an actual melacha and it does not risk leading to the violation of another melacha. The halakha is derived from the pasuk in Isaiah (58:13) describing Shabbat that reads “and you will honor it by not…pursuing your affairs.” Chazal explained that concern with weekday affairs is forbidden, even if we do not perform an actual melacha. My thinking was that both sports and Model Congress represent participatory activities, which is the issue that is referenced in the Shulchan Aruch. By contrast, the awards ceremony under contemplation is a passive activity – no debating, presenting or playing, – just sitting and listening.

5. I believe that students must sense that we are not striving to use halakha as a mechanism to forbid things; the goal is to show them by example the beauty of a system that provides an objective guide to help us live our lives in a meaningful way. Were I to forego the full process of considering the issue and simply declare the practice asur, I believe our impressionable students would consider our stated goals as little more than lip service. While the Boiling Point staff was not thrilled with my decision, I believe they respected the process by which it was reached because they knew I really worked through the issues and came to the conclusion after fully considering the issues at hand.

So, to the parent who emailed me regarding a prospective parent’s concerns, and others in the community who were similarly concerned, I do hope that you will recognize that there is important, in my mind fundamentally important, value in considering seriously each issue and not immediately ruling on the question. You can choose to disagree with me (as some will disagree with me forbidding it as well!), but I would hate to think we live in a community that would frown upon us even considering issues from all sides before issuing a halakhic ruling. For those who want to engage in this kind of critical thinking and halachik inquiry, Shalhevet is the place for you.

Which brings me to the final issue that I want to raise. I was invited to attend a bat mitzvah this coming Shabbat that will be done in the style of Shirah Chadasha. For those of you who do not know, Shirah Chadasha is a minyan in Yerushalayim that, in its own words, seeks to “create a synagogue where we could increase participation of congregants, and particularly maximize the involvement of women in our services . . . all within the rules and rituals of Orthodox Judaism.” In the spirit of all I have explained above, I want to share with you the rudiments of my own halakhic analysis in coming to the decision to participate in this family’s simcha. While Atara and I would not necessarily choose this style of ceremony for our daughters, the issue is certainly one that can be reasonably debated.

Respected Torah scholars such as Rav Daniel Sperber and Rabbi Yehuda Herzl Henkin (the author of the halakhic work Bnei Banim) have permitted the reading of Torah by women in public settings since the principle of kevod ha-beriyot (compassion for human beings) overrides that of kevod ha-tsibur (the reasoning why such an action is forbidden). Here are two important articles on the topic:

- http://www.edah.org/backend/JournalArticle/3_2_Sperber.pdf

- http://www.edah.org/backend/JournalArticle/1_2_henkin.pdf

Having gone over a number of sources and consulted with some of my advisors, I feel comfortable supporting an individual family choosing to follow these halakhic sources and ideas and having a service at which women read the Torah and lead those tefilot that do not require a minyan.

That being said, I would not host such a tefilah service at the school as we are servicing a mainstream population and I believe that the halakhic decisions for the school need to keep that in mind. This goes to the various factors that I mentioned above that I need to consider in making a decision for the school community.

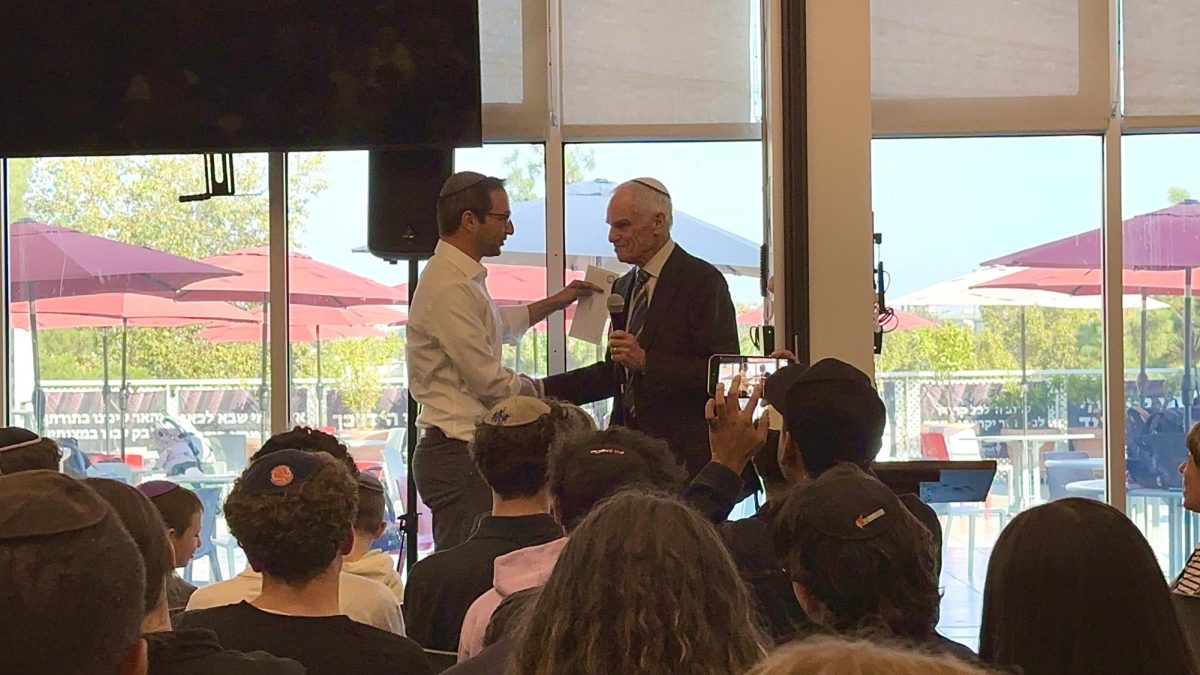

Therefore, when I was asked to attend, I was honored that a family would want me to be a part of their Simcha. I do have incredible respect for them and their choice of this style of tefilah to celebrate this milestone for the entire family – and I plan to attend the service and share in their simcha. In addition, I look forward to sharing words of torah at the end of the tefilah.

To close, I would like to share a story I heard from Rabbi Elazar Muskin at one of his inspiring yamim noraim speeches. Fortunately I was able to track it down at My Obiter Dicta “American Olim in Israel: The Challenge (Part 2)“, [posted by Rabbi Jeffrey Woolf, June 28, 2012] He reports that…

The pre-war Jewish community of Kovno (Kaunas, today) Lithuania was divided into different components, divided by the Neris River. On the one side was the general community, which was made up of every type of contemporary Jewish religious and cultural population. Indeed, the community was a bit notorious for a lackadaisical form of religiosity. On the other side of the Williampol bridge, was the famous Slabodka Yeshiva, a flagship of the Mussar Movement.

Relations between the two sectors were often tense. There was a saying attributed to the Alter of Slabodka, R. Nosson Zvi Finkel zt”l, that the bridge from Kovno to Slabodko only went one way.

Coping with the myriad of challenges, modernization and secularization in Kovno was its illustrious rabbi, R. Avraham Dov-Bear Kahana-Shapira zt”l, author of the classic collection of responsa and Talmudic essays D’var Avraham, and known more popularly as the ‘Kovner Rov.’ One central concern of his was the alienation of young Kovner Jews from the synagogue. Thus, when the administration of the Choral Synagogue came to him with an intriguing approach to the problem, he jumped at it.

The idea was to have the synagogue’s cantor, the internationally renowned tenor Misha Alexandrovich, offer public concerts that would feature classical chazzanut alongside renditions of serene Italian bel canto compositions. The hope was that this type of cultural evening would draw modernizing young Jewish men and women to the synagogue, where they would socialize and (perhaps) find mates.

The first concert was a smashing success and more were planned. Everyone was thrilled, except for the heads of the Slabodka Yeshiva. They turned angrily to the Kovner Rov and demanded that he intervene to stop the concerts. They were indecent, the Rashei Yeshiva objected. They led to fraternization between men and women, and in the synagogue. Worse still, they might corrupt yeshiva students.

The Kovner Rav listened respectfully, and responded firmly: The great rabbis of the yeshiva are responsible for the yeshiva, not the community. The concerts are good for the community and they are to continue.

I am mindful that as head of school, my actions will reflect upon the entire school community. I hope you can understand the principles I have employed to make this decision, and the distinction between decisions that bear directly upon the school’s policy and decisions that support a family’s particular halakhic choices.

Let me end this week’s column with more words from the Seridei Eish: “One must not be afraid of the masses’ screaming, and of rabbis who wish to glorify themselves with their stringency.”

Shabbat Shalom.

RELATED: NSPA will host separate award program so Shalhevet group can attend after Shabbat