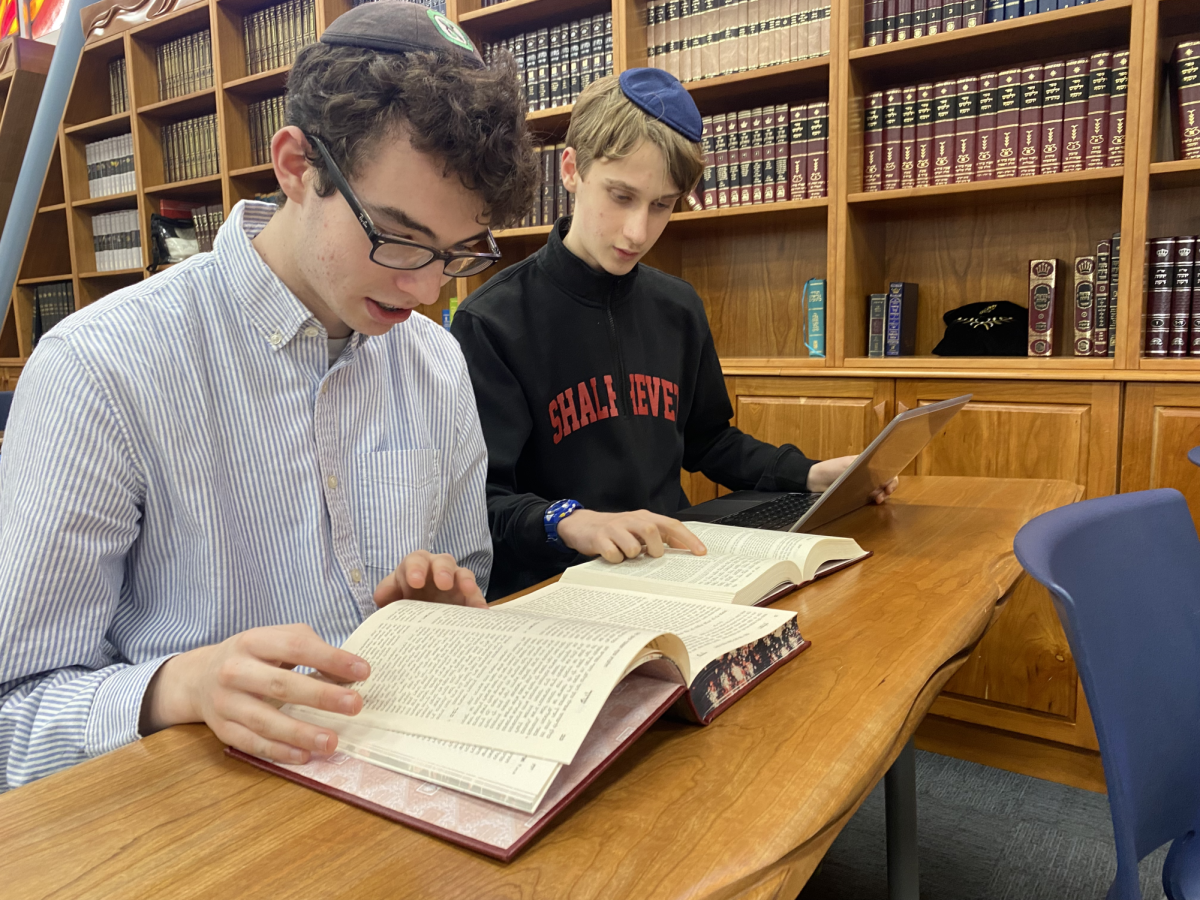

The fifth perek, or chapter, of Parshat Ve’etchanan includes the repetition of the Ten Commandments, first revealed in Shemot in Parshat Yitro. In Ve’etchanan, the section starts off with a straightforward pasuk (verse), in which Moshe tells B’nei Yisrael to hear the laws that he is telling them, and to observe them.

Moshe then says, referring to those commandments, that Hashem made a covenant with B’nai Yisrael at Chorev. What and where is Chorev? This is the first time it has been mentioned so far, anywhere in the Torah.

Because of the context, we generally understand Chorev to be another name for Har Sinai – one of many, in fact, in Tanach. This is what Ibn Ezra says in his commentary on the pasuk — simply that Chorev is Sinai. Then why not just say Sinai? What is the Torah’s reason?

Many of today’s rabbis, citing various midrashot – additional meanings gleaned by rabbinic commentators – understand each of the different names for Har Sinai – such as Har Chorev and Har Bashan, another example of a different name for Har Sinai – as teaching us something in particular. For instance, they claim that Har Sinai is called Har Chorev because of the word cherev, sword, which tells us that the authority to establish the death penalty was given at Sinai. For Bashan, they say that the name comes from the word shen, meaning tooth, which tells us that Torah helps nourish us.

This doesn’t answer our question; each of those is just a play on words and merely homiletical. They contain no reasons why certain names for Har Sinai are used in certain cases. The answers given are thus not critical examinations of Torah.

Ramban has a better answer. Commenting on the beginning of Shemot perek 19, Ramban states that Chorev is the wilderness around Har Sinai, and not actually the same place as Sinai. Why would the Cherev wilderness, as opposed to Har Sinai, be mentioned in this location?

Because when B’ nai Yisrael received the Ten Commandments in Parshat Yitro, it was Moshe telling the people at the base of the mountain – a place Ramban would call Chorev – what Hashem had told him up on the mountain. Perhaps the word Chorev is used in this case to emphasize the intended audience located beyond Har Sinai – B’nai Yisrael, rather than Moshe on the mountain itself.

In further evidence, the Torah states that anyone who would try to ascend Har Sinai would die; only Moshe was able to actually travel up the mountain. In Parashat Yitro, the focus is placed on Moshe, who introduces the Ten Commandments by saying, “Hashem spoke to me saying….” In Ve’etchanan, the narrative is shifted towards Bnei Yisrael, referring to the covenant they made with Hashem at Chorev. There is no mention of Moshe receiving the Ten Commandments from Hashem in Ve’etchanan.

To understand why the narrative centers around B’nei Yisrael as opposed to Moshe, it’s necessary to study the context. We are, of course, in Sefer Devarim, during Moshe’s final speech before he dies. B’nei Yisrael will soon have to live without Moshe, so they have to understand that the covenant applies to them. They will be going to Israel very soon, and they need to prepare to create a just society in Israel, based on the values and statutes in the Torah. Moshe will not be there for them, so here in Devarim they have to accept the Ten Commandments for themselves.

Jews have always understood that the personal responsibilities involved in being a mamlekhet kohanim and goy kadosh – a kingdom of priests and a holy nation – rest not just upon the leaders of our communities, but also upon each of us as members of the community. We must uphold the Ten Commandments, remembering that the Torah applies to everyone equally and continue to accept them ourselves and improve the world around us.

There’s a direct parallel to Shalhevet as well. While the action might be happening up at Har Sinai with Moshe, the covenant with God was also made with us, down in Chorev. Recognizing that, we students should remember, as the school year comes to a start, that we all bear this responsibility – not just the faculty. This is our duty, as Jews.