‘All those who are impure, even niddot, arepermitted to hold a Torah scroll and to read from it, for the words of Torah are not susceptible totum’ah (impurity). This is provided that his hands are not filthy or dirty with mud; they should wash their hands and then touch it.’

—Rambam, Hilchhot Kriyot Shema 4:8, cited by the Shulchan Aruch

For those who base their opinion about women carrying the Torah on tradition, feminist values, or the way they were raised, there’s another factor to consider: Halacha – Jewish law – deems it acceptable.

Even if they opposed the practice, none of the dozen-plus synagogue and school leaders interviewed by The Boiling Point argued that it was against Jewish law.

That’s probably because every rabbinic authority agrees that there is no prohibition against women carrying, holding or touching the Torah. The Shulchan Aruch, which is used as a baseline for halacha, says that the only criterion for being able to touch the Torah is the physical cleanliness of ones’ hands — not gender, age, or even religion.

All accepted sources say that from a ritual standpoint, things that create a state of spiritual impurity – among them, parts of a woman’s monthly cycle, a man’s having experienced an emission, or a person’s having come into contact with a corpse – affect the person involved, but not a Torah scroll.

“All those who are impure, even niddot, [menstruating women] and even a kuti [non-Jew] are permitted to hold a Torah scroll and to read from it, for the words of Torah are not susceptible to tum’ah [impurity],” wrote the Rambam in Orah Hayyim. “This is provided that his hands are not filthy or dirty with mud; they should wash their hands and then touch it.”

Rambam’s statement is cited by both the Tur and the Shulchan Aruch as law.

The only possible dispute, then, would be an interpretation of a baraita, orTalmudic teaching, by the Ravya, who lived at the same time as the Rambam but received much less recognition. The following is an excerpt from what Ravyah wrote in Brachot Volume 1, #68:

“And the women practice dignity and separation and do not enter the synagogue at the time of their niddah. Even when they pray, they do not stand before other women.”

The Ravyah goes even further and says that no one who is spiritually impure can touch a Sefer Torah – not even men.

“This custom is appropriate, as we say regarding the ba’al keri: I have heard there are those who lenient and those who are strict, and all who are strict, his days and years are lengthened (Ber. 22a).”

But that opinion has long since been dismissed in terms of what Jewish communities follow, because Rambam and the Shulchan Aruch carry the weight in deciding halacha, and the Ravyah doesn’t.

Here’s what Rav Moshe Isserles (Rema), the accepted Ashkenazic posek, says about the laws of impurity: “There are those who wrote that a woman in niddah while in the days of her bleeding should not enter the synagogue, pray, mention God’s name, or touch a Torah scroll,” says Rema. “And there are those who say she is permitted to do all of the above and this is correct (Rashi, Hilkhot Niddah 4:3).However, the custom in these countries follows the first opinion.”

In other words, some say an impure woman can’t touch a Torah and some say she can, and the latter opinion is the right one. But the “custom” is the opposite.

Thus it is that 800 years later, most Orthodox synagogues in Los Angeles do not allow women to carry the Torah during any part of its tri-weekly parade through the congregation .

Several, including Nessah Synagogue, Beth Jacob Congregation and Etz Jacob, do allow women to kiss the Torah as it is carried through their section by a man.

And at B’nai David-Judea on Pico and the Westwood Village Synagogue near UCLA, women carry the scroll through their own section for themselves.

“The Shulchan Aruch is absolutely explicit that women may hold the Torah, there’s just no question about it,” said B’nai David’s Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky.

Why do Orthodox shuls prevent women from carrying the Torah if there’s no legislative reasoning behind it?

“The women do not hold or touch the Torah because that was considered to be not the practice,” said Rabbi Moshe Cohen of Aish Hatorah, an Orthodox synagogue on Pico and Doheny, thus citing tradition. He went on to speculate that impurity issues might be involved, referring to women’s monthly immersion in the mikveh, or ritual pool, which ends their state of niddah.

“A lot of these things are just not the common practice,” Rabbi Cohen said, “even though maybe technically if she had been to a mikvah it would be allowed.”

Nessah Synagogue, a Sephardic congregation on Rexford and Wilshire in Beverly Hills, has a slightly different custom, citing only tradition.

“During the prayer, we don’t let the ladies [carry the Torah],” said Rabbi David Shofet, the Rabbi of Nessah. “During Simchat Torah, they can hold, kiss, and touch the Torah… but when we pray during Shabbat, the women don’t carry it. They’re not praying during that time, everyone else is dancing.”

Asked why, Rabbi Shofet replied, “There’s no why — we just don’t do it.”

Rabbi Kanefsky overrides tradition with basic halacha, though he doesn’t do that lightly. Tradition, too, is important, he said.

“I very much believe that we don’t make changes in tradition simply for the sake of making changes in tradition,” Rabbi Kanefsky said in an interview. “There has to be a compelling reason.

“What ranks especially high as a compelling reason is when the tradition is opposing or undermining one of our most important religious efforts, which in this case is to enhance the connection of our women to the study of Torah,” he continued. “Withholding of the sefer Torah from women undermines the efforts that we’re making.”

Ironically, Rabbi Cohen and some others see changes in women’s roles as a reason to keep synagogue practice the way it is.

“The issue is very much tied up with the politics like feminism,” Rabbi Cohen said. “It’s not that women don’t have roles to play; they do. But when rabbis see that it is being politicized, and not coming from a spiritual place – ‘We want to show that we are equal to the men. Anything you can do, we can do also’ – that’s not the way rabbis look at it, they want to see that it’s coming from a pure place.”

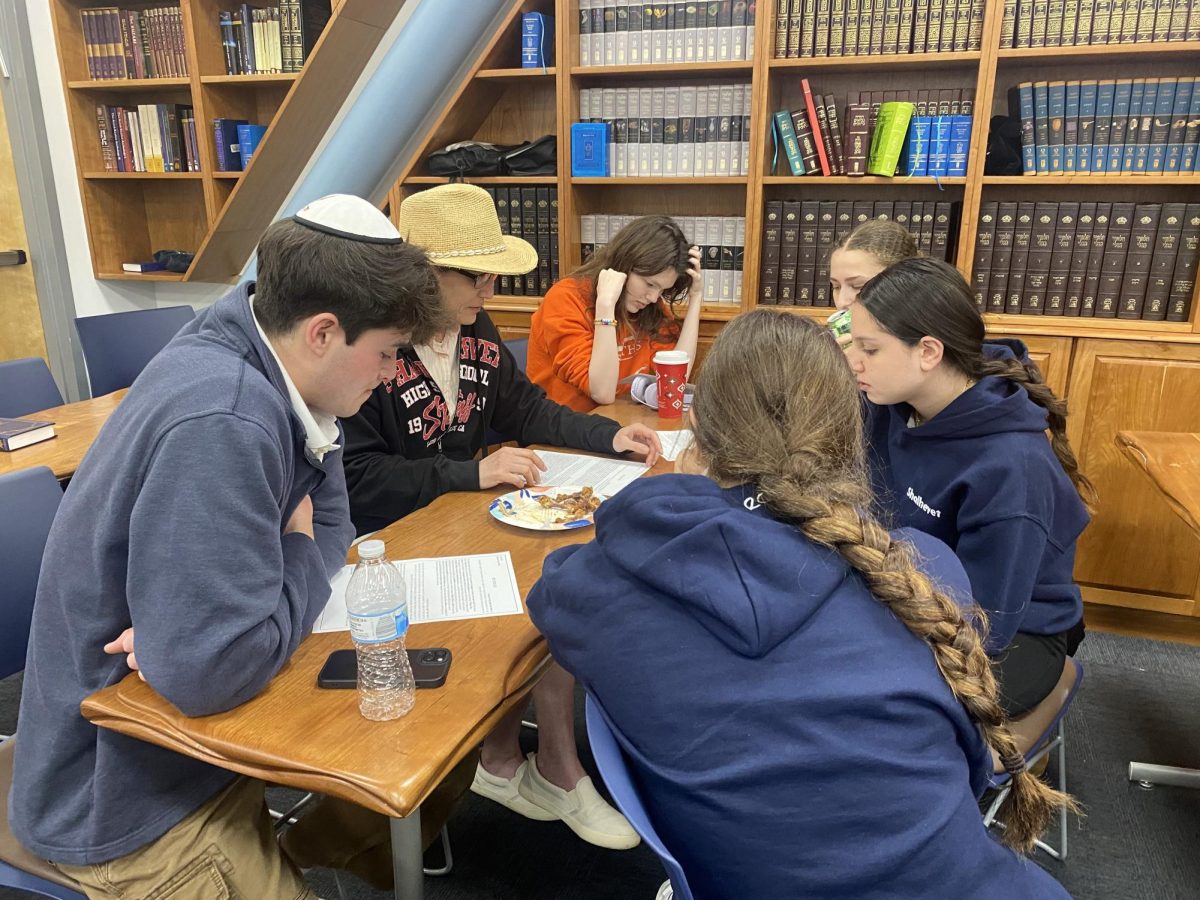

But Shalhevet girls who have carried the Torah say it has nothing to do with the boys.

“Even though I come from a really strict Sephardic background, I actually like it,” said sophomore Sarah Soroudi. “I feel a connection to Judaism and to God when I carry it; I don’t know how to explain it.”

Judaic Studies teacher Ruthie Skaist has never carried a Torah herself because she grew up in a shul that didn’t allow it and went to an all-girls school where it wasn’t allowed. But she has seen girls enjoy it.

“I understand the point of tradition, and I respect it,” Mrs. Skaist said. “But when it’s something that brings people so much joy, brings them closer to God, and is halachically acceptable, I don’t understand why it would be taken away,” said Mrs. Skaist.

In any case, even the most Orthodox rabbis agree that there is no halachic problem and that it’s just a matter of custom. And because Judaism respects tradition, there hasn’t been any reason to change it in the 800 years since the Rambam lived — until now.

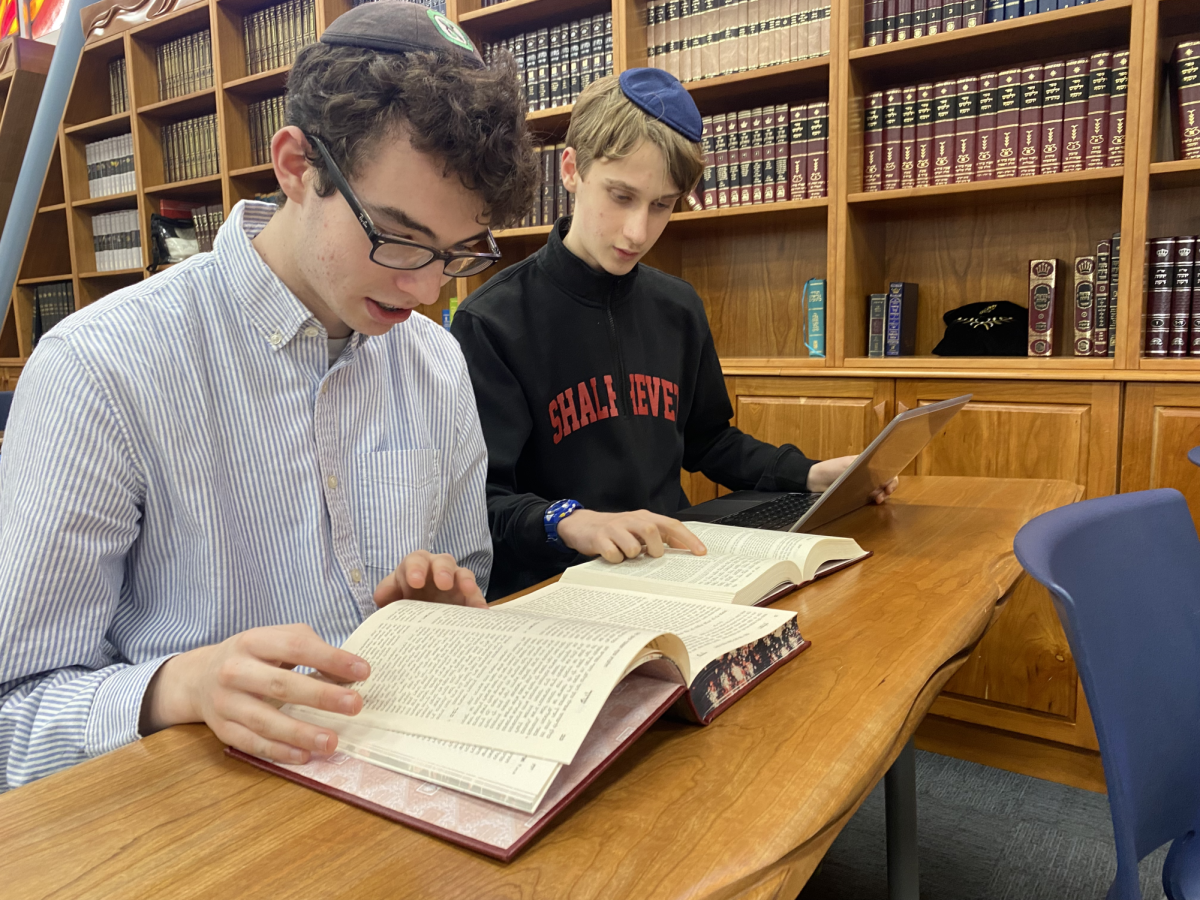

Rabbi Ari Schwarzberg, Judaic Studies teacher, makes a clear distinction between what is allowed and what is done.

Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Ari Schwarzberg said Jewish practice reflects an interaction between law and history. He said part of Judaism is its ability to incorporate ever-changing modern situations – such as the invention of electricity, which required a new look at the laws of Shabbat, and now, women’s getting an education. Neither existed when these books were written.

In the past, he said, the same rabbis who said it was legal for women to carry the Torah did not necessarily advocate it. They might not have advocated women learning gemarah either.

“Just because it’s legally okay according to the Rambam and the Shulchan Aruch doesn’t mean that the Rambam and the Shulchan Aruch would have promoted women carrying the Torah as part of a ritual,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said.

But now it is the norm for women to become educated, go to shul, and have a more active role in prayer, so practice can be changed since Halacha allows it anyway.

“This wasn’t done before because of tradition – however, one of the greatest features of our tradition is that we have a built-in elasticity in halacha,” Rabbi Schwarzberg said. “We have the ability to adapt the traditions to the needs of our communities. And just because the Rambam didn’t do it, we have the ability to change customs for our times. Traditionally, women didn’t do it for the reason women didn’t do a lot of things.”

It’s possible that as this generation’s yeshiva students, who are the first to look at the rules about women carrying the Torah at a time when women themselves are studying them, grow up and take over shuls, they will gradually all allow women to carry the Torah.

Among them may be graduates of Shalhevet, where new Head of School Rabbi Ari Segal has affirmed the practice even though some boys objected.

But in 2011, tradition is still the most important factor to a lot of people.

“That’s not the practice in the shul, not because it’s forbidden, but there’s a certain standard that we operate with so that people who come there know what to expect,” Rabbi Cohen said.

VIDEO: Two problems solved at once as Sephardic minyan debuts 11/10/2011

Related story: About 50 students attend school’s first Sephardic minyan 11/7/2011

EDITORIAL: On women and Torah, Shalhevet should lead 11/4/2011

Related: Shalhevet stands alone among Orthodox schools in letting girls carry Torah, survey finds 11/3/2011

Related: Rabbi Segal okays first Sephardic minyan; no changes to Ashkenazic minyans 10/31/2011

Related: Meeting yesterday began process of minyan decisions, Rabbi Segal says 10/26/2011

Related: Girls will no longer carry Torah at junior-senior minyan 10/7/2011