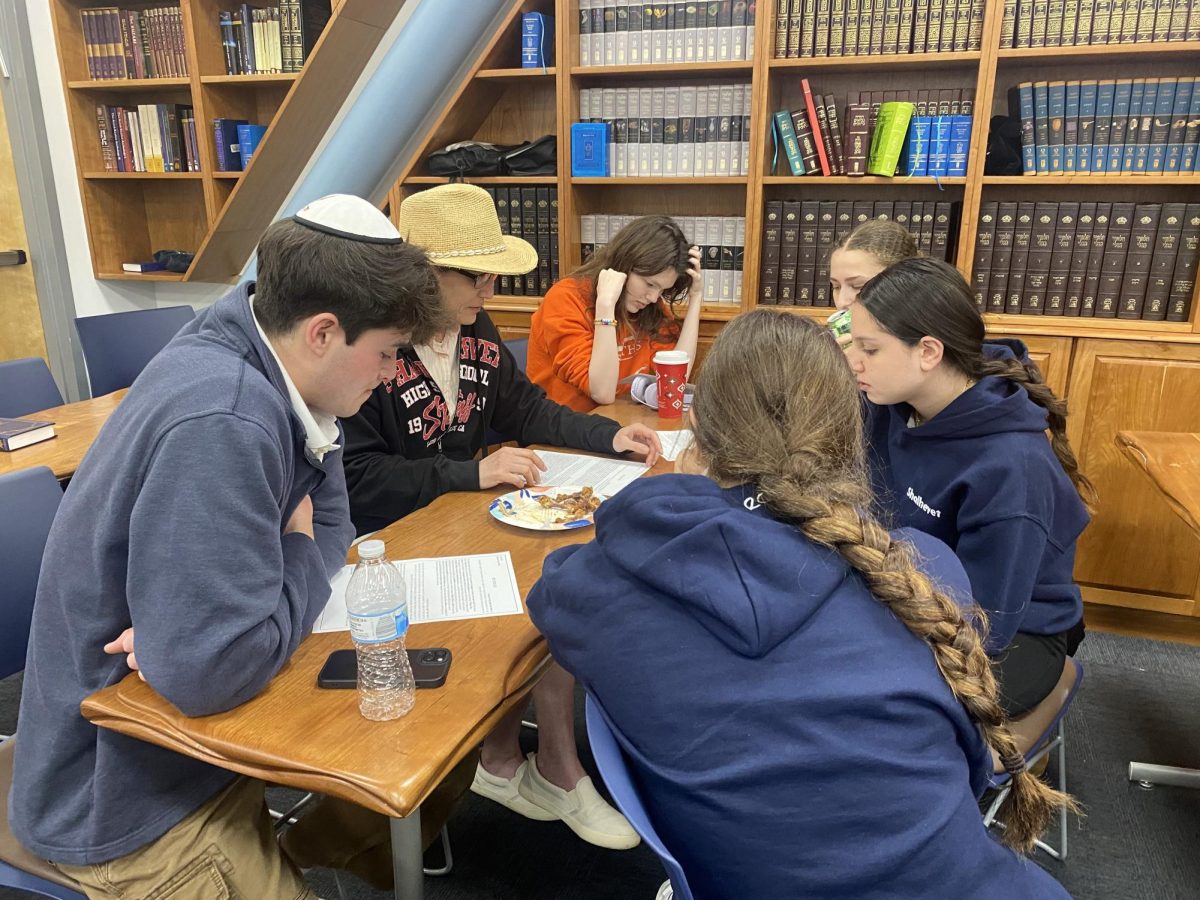

Women rabbis. Some people cringe at the idea. Some leap out of their chairs in excitement. So of course, in a classic expression of Shalhevet’s love for controversy, it was the Town Hall topic April 29.

At a conference in New York April 27, the Rabbinical Council of America approved a resolution stating that they “cannot accept either the ordination of women or the recognition of women as members of the Orthodox rabbinate, regardless of the title.” (http://www.forward.com/articles/127573)

But at Shalhevet, no one seemed to think that was the last word on the subject.

“I don’t see the difference between capabilities of men and women,” said junior Eliana Willis at Town Hall. “We lose great minds that are just as capable because of this law.”

“I feel like my religion is dominated by the male populace and opinion,” said Rose Bern, a freshman, at the microphone. “It’s inappropriate that women can’t be rabbis because of their gender.”

Junior Nathaniel Kukurudz responded to Rose with the complete opposite opinion.

“I don’t understand why women want to take up the same roles as men, even though the two are obviously incomparable,” he said. “Men and women have different jobs.”

The New York meeting and resolution were arranged in light of the actions of Rabbi Avi Weiss of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale – also the founder and head of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, the Modern Orthodox rabbinical school where Judaic Studies Principal Rabbi Ari Leubitz was ordained.

As the Town Hall handout read, “Weiss sparked outrage in January when he conferred the title of ‘Rabbah’ — a feminized version of rabbi — on Sara Hurwitz, a member of the clerical staff of his New York synagogue.”

“Clerical” in this sense refers to “clergy,” not to a clerk or bookkeeper. According to news reports, Hurwitz was already doing most of what a rabbi does: she teaches classes, gives speeches, visits the sick and elderly, studies with bat mitzvah girls, and gives spiritual and halachic assistance.

In addition, Rabbi Weiss and Ms. Hurwitz are currently taking applications for Yeshivat Maharat, a recently established yeshiva that accepts Orthodox women into a full four-year learning program. That program, too, has been met with criticism.

“I don’t see how this promotes the growth of women’s learning,” Rabbi Yosef Blau, the spiritual advisor of Yeshiva University’s rabbinical seminary, told HaAretz newspaper (http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/news/an-orthodox-woman-rabbi-by-any-other-name-1.276624). “It makes it more controversial and more difficult for women who are ready and who are committed to learning.”

Rabbi Weiss said he conferred the title “rabbah” on Ms. Hurwitz in recognition of her high level of learning and the role she was playing in his shul. But when the RCA threatened to expel him, he retracted it. Yeshivat Maharat will continue to operate, however.

RCA is the umbrella faction of mainstream Orthodox rabbis, many of whom are Modern Orthodox. The April 29 resolution officially opposes the ordination of women as rabbis, but continues to support the creation of “halachically and communally appropriate professional opportunities” for female scholars.

This was seen as a compromise, denying Ms. Hurwitz the title but encouraging Yeshivat Maharat as an institution that offers young Orthodox women an advanced Torah education.

Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky, rabbi of Modern Orthodox synagogue Bnai David Judea, in fact flew to New York so he could vote on the issue and try to influence the debate.

“There will and should be a day that women are rabbis,” Rabbi Kanesfky told The Boiling Point after he returned. “It’s the logical conclusion after we’ve flung open the doors of co-ed Jewish education.”

He believes that women eventually – though not yet – should be rabbis because of the uniquely feminine skills and approaches women bring and also because the Jewish community is always in need of skilled and intelligent rabbis. He said he wanted to be a part of the RCA deliberation because he believes that Rabbi Weiss’s rabbinical ordinance of women was not grounds for expulsion.

Even so, he understands the decision of the RCA.

“This wasn’t the time to introduce women rabbis,” says Rabbi Kanefsky. “The community wasn’t ready. Some natural and organic steps still need to be taken.”

Natural steps, he says, would include the emergence of a fully functioning class of clerical women that is heavily involved with the synagogue. If a generation grows up with such a strong influence of women as leaders, the next steps will unfold on their own, even if it takes 20 or 30 years, he said.

Rabbi Leubitz is also at ease with the RCA’s decision.

“I’m glad the issue was worked out,” says Rabbi Leubitz. “It’s a bad thing when two groups in Judaism fight. I’m happy that they were able to make a compromise.”

Moreover, he says, the compromise is noteworthy. Rabbi Leubitz says that although we aren’t ready to welcome an order of women rabbis, women have come a very long way in terms of activism in Judaism.

Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Chaim Ovadia, on the other hand, thinks the RCA compromise fell short. Rabbi Ovadia fully supports women as rabbis and was very unhappy that Rabbi Weiss agreed to stop conferring the title of rabbah.

“There will always be social pressure on women,” said Rabbi Ovadia in an interview with The Boiling Point. “A time will come when they have a critical mass and will really be able to make a change.”

The RCA resolution will probably not quiet the debate in some people’s minds, including many at Shalhevet.

“I literally see no problem with women rabbis,” said junior Joseph Nemetz, who attends the Conservative synagogue Temple Beth Am where Rabbi Susan Leider has served as associate rabbi and leader of the Beit Tefillah minyan for many years. “The only argument I’ve ever heard against it is that men in the same profession would be distracted by female rabbis. But this is a ridiculous claim.”

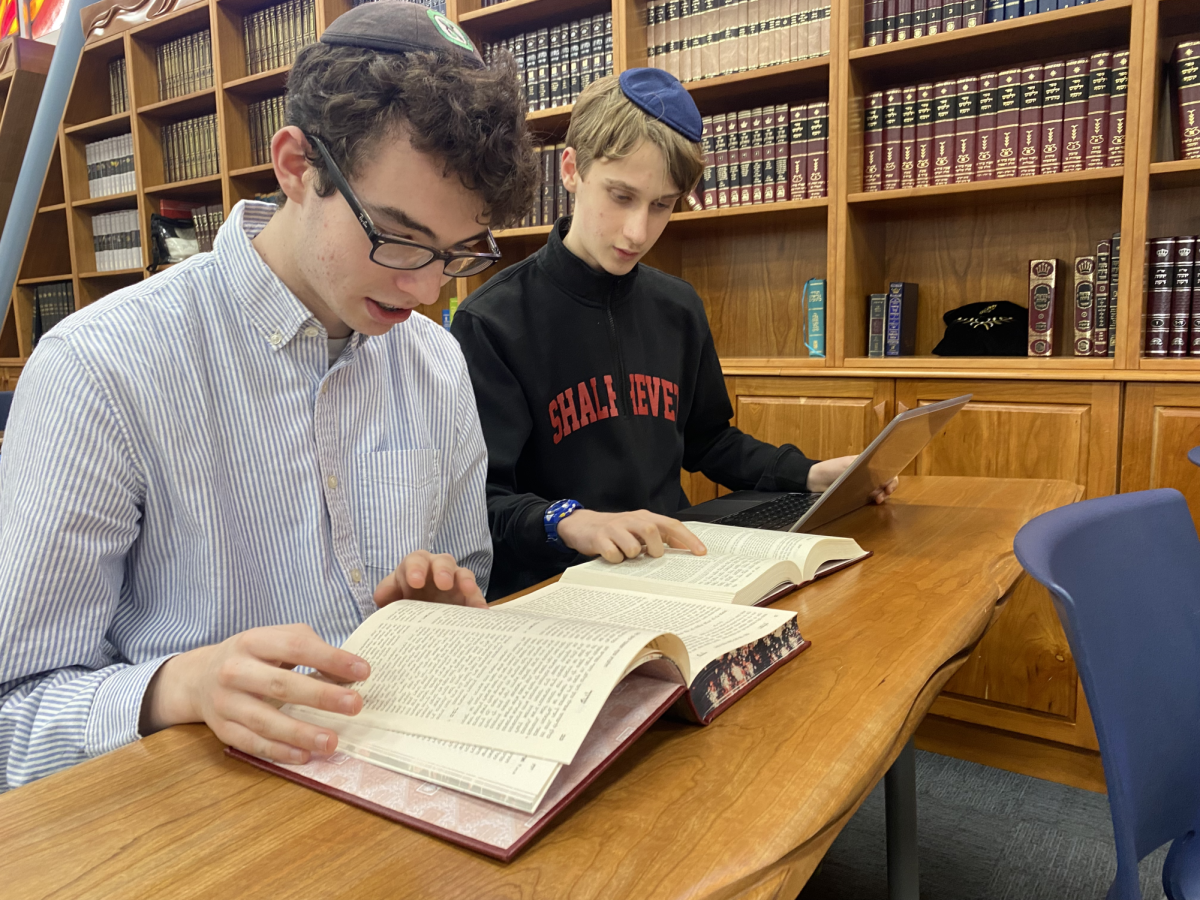

Gemara teacher Mr. Noam Weissman disapproved of the way the people were forming their opinions on the matter at Town Hall. The issue of women rabbis is a halachic issue, he said, and should be approached logically using rabbinic precedents, rather than with an emotional response.

“Halachic Judaism from an Orthodox perspective has a specific procedure and specific principles,” Mr. Weissman told Town Hall. “You can’t just decide whether or not something is alright in Judaism from an emotional perspective. You have to consider the issue from a legal perspective.”

Mr. Weissman brought up the halachic issue of heter hara’ah; or issue of who is permitted to render legal decisions in Judaism. One of the problems with women rendering halachic decisions – as rabbis must – is that women are, according to the Torah, not permitted to testify in legal proceedings.

Does that mean women also cannot make laws? Or have there been other rabbinic precedents which annulled this halacha?

“There are answers to all of these questions,” Mr. Weissman said, though he did not say what they were. He encouraged students to try to find the answers themselves or in class. “You just have to refer to previous precedents and rulings.”

That did not persuade Eliana Willis, who said, “It’s just silly. This isn’t about rabbinic precedents; it’s about right or wrong.”

Nathaniel Kukurudz, in line with Mr. Weissman’s comment, brought up his own precedent during his turn at the microphone: the Rambam’s interpretation of the pasuk from Parshat Kedoshim that commands the Jewish people to “be holy” – kedoshim tehiyu.

According to the Rambam, Nathaniel said, this verse is commanding the Jewish people not to search for loopholes in halacha or in the Torah in order to accomplish something that isn’t accepted in Jewish culture – in this case, the rabbinic ordinance of women.

“Women should be honest to themselves and understand that the Torah doesn’t need to explicitly prohibit them from becoming rabbis,” said Nathaniel, “because it is obvious that the Torah does not endorse it.

“Let’s not look for the loopholes,” he continued. “Deep down, I’m sure all of us would agree that the Torah doesn’t have to state every prohibition. Otherwise, it would just be a book that lists various ‘thou shalt not’s.’ That isn’t the goal of the Torah.”

Rabbi Ovadia also agreed that rabbinic precedents must be considered – but he thinks those same precedents, along with the current social conditions of women in Judaism, point the other way.

In regards to the law that women cannot testify in court, he said there is a big difference between serving a rabbinical court and operating a shul. On a cultural level, he said some women are practically functioning rabbis already.

“A rabbi needs to be a spiritual leader, which many women already are,” Rabbi Ovadia said. “A rabbi also needs to determine halacha, which women do and did. Many Jewish women know a lot of practical halacha and make decisions on it every day.”

At Town Hall that day, fewer people argued against women’s ordination than in favor of it, perhaps reflecting cultural change that has already begun.

Rabbi Ovadia noted that religious women today are learning in yeshivas that are just as good as if not better than most male yeshivot – which he said would have been unheard of 100 years ago.

Opinion Editor Zev Hurwitz and Editor-in-chief Lexi Gelb contributed to this story.