Whodunnit? Biology class analyzes ‘artificial vomit’ to solve murder mystery

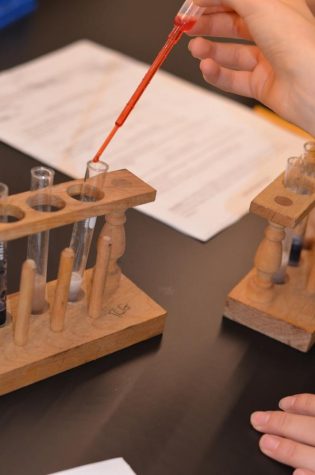

CHEMICALS: Freshmen in Dr. Basheer’s biology classes began their lab by adding murky, brown ‘artificial vomit’ to test tubes. Soon, they added other substances to form a solution that would turn the liquid other colors, depending on whether it was a carb, protein, or lipid.

Holding the test tube as far away as possible, freshman Evy Rosenkranz crossed the classroom hoping that the chunky, brown and smelly mixture wouldn’t spill.

The substance was part of a lab exercise in Dr. Elizabeth Basheer’s freshman Biology class, and it was supposed to be vomit — a key piece of evidence in a murder mystery whose clues all had to do with what the victim had been eating before he died.

“It looked so real, and I was worried it would get on me,” said Evy said.

The various “suspects,” the story went, had all been at different restaurants at the time of the crime, each serving food that would break down into different macromolecules — things like lipids, carbohydrates and proteins.

So to find the murderer, students had to investigate the contents of the victim’s stomach to determine where he had last eaten. Whoever’s whereabouts matched the victim’s stomach contents would be the murderer.

Dr. Basheer created the brown mixture — supposed stomach contents, or an artificial “vomit” — to solve the crime.

Freshman Gaby Bentolila said it grossed her out because it looked so real.

“When I saw the vomit, even though it was artificial, it made me want to vomit myself,” said Gaby.

CAREFUL: Students walked around the class holding test tubes and mixing substances. Some worried that the ‘artificial vomit’ would spill on them.

Some thought the smell was neither good nor bad; others thought it smelled like dog food. To many it looked real and smelled familiar.

“It smelled a little bit like noodles,” said freshman Yaakov Berg.

Dr. Basheer said she found the lab online and chose it because it was “hands-on.”

“If you had never seen a sunset and I just said it is a big yellow ball that goes down past the horizon, that sounds plain and boring,” Dr. Basheer said. “But if you get to see a sunset and experience a sunset firsthand, you can learn a lot more. Same with hands-on labs.”

The teacher said she blended boiled noodles, olive oil and baked beans to make the substance.

“I really wanted to engage the students and make the artificial vomit as real as possible and as disgusting as possible,” Dr. Basheer said in an interview.

Entering the classroom at the beginning of C block Sept. 18., the first thing the students saw was the unusual mixture, which was sitting in a beaker the size of a jug of water. Many made repulsed faces while others were amused.

Test tubes and instructions were handed out and there were gloves available for those who were extremely disgusted.

As the class went on, vague nausea started to fade away and was replaced by looks of determination to find which suspect was guilty.

“At first I was disgusted because I thought the throw-up was real,” said freshman Shani Menna. “But eventually I discovered that it was made up and she just included the macromolecules needed, without supplying real throw-up.”

TEST: A student adds Sudan III Stain to “vomit” to test for lipids (fats). If lipids are present, fat cells will turn bright red and will separate and go to the liquids surface.

In order to find the murderer, students had to combine the artificial vomit with various chemical solutions that would identify macromolecules. Students ran from one side of the room to the other clutching the test tubes and various chemicals.

In the presence of starch, iodine would turn purple, blue or black. This would mean that the victim had eaten starch — so a suspect who had claimed to have been at a restaurant that served starch could potentially be the murderer.

In the presence of sugars, Benedict’s Solution added to the vomit would change from blue to yellow, green, or brick red. And in the presence of protein, such as pasta or potatoes, Biuret Solution would turn to pinkish purple.

The possible resturants were Frankie Bones, which served buttery pasta and olive oil; Fat Baby’s Pizza; and The Smokehouse, which served wings and celery. Lipids and carbohydrates were more likely to be found at Frankie Bones, while lipids, carbs and protein could all be found at Fat Baby’s Pizza. The Smokehouse would most likely show up as carbohydrates and proteins.

Test tubes with a mixture of the artificial vomit and Benedict’s solution had to be carefully placed in hot water for about 40 seconds, then taken out using a test-tube holder. Some students worried that they would drop the container.

SUSPECTS: Ninth-graders hypothesized who the murderer might be based on the story told by Dr. Basheer, and got ready for the lab by choosing which mixture to start with.

When the lab was finished, the results were that the victim had eaten food that contained lipids and carbs — not protein — which meant he had eaten at Frankie Bones, the same place his girlfriend had eaten. This meant that the girlfriend was the murderer.

While a lab based on vomit might have seemed unappealing at first, students said it strengthened their knowledge of macromolecules.

“Most labs are not especially interesting,” said Yakov Berg. “This lab was a lot more fun because there was a story behind it that we had to figure out. It’s just fun to solve a mystery.”

Molly is studying at Midreshet Torah v'Avodah seminary in Jerusalem and will attend Columbia University in New York next year.