Call of Duty took gamers to the heart of a war-torn Middle East, while Fallout 3 unfolded in the midst of a post-apocalyptic Washington, D.C. Now Farmville brings users to the heart of the action: The family farm.

For those who have not had their notifications exhausted by “farm-pushers,” Farmville is an online Facebook application that lets users tend a virtual plot of land on which they grow and sell crops and expand their farms in pursuit of the cyber-American dream. Unfortunately for some, turning the virtual wheels of capitalism for hours on end takes its academic toll.

“I think it’s bad for students, even though I do it myself,” confessed Michael Lenett, a freshman and Level 25 farmer with 21 “achievements.” “If you think of it, you can spend hours on your farm, expanding and buying things, organizing it, and sometimes it can take away from school work. But it’s fun, and that’s why people do it.”

Farmville has reached about 80 million monthly users, according to the game’s Facebook information page, meaning about one in five Facebook subscribers are involved.

Games and applications these days like to insinuate themselves into Facebook to use the resources of social networks and leech into a circle of friends. In Farmville, users can send “farm items” and “neighbor requests” to their friends, which manifest in requests on the receiver’s profile. Users can only expand their farms by interacting more with Farmville, either with the computer or with fellow farmers.

“You don’t just begin the game and have everything at your feet,” explains freshman Leora Nimmer. “The higher the levels and points that you receive, the more opportunity you have to make money and plant different types of crops. You climb up the ladder throughout the game, so people have a continuous goal every time they sign on.”

Not everyone plays, and some farmers have managed to give it up.

“I don’t like it anymore,” said freshman Becca Ordin, a Level 21 ex-farmer who once held 22 achievements. “I think there’s no point at all, all you do is wait for your crops to grow.”

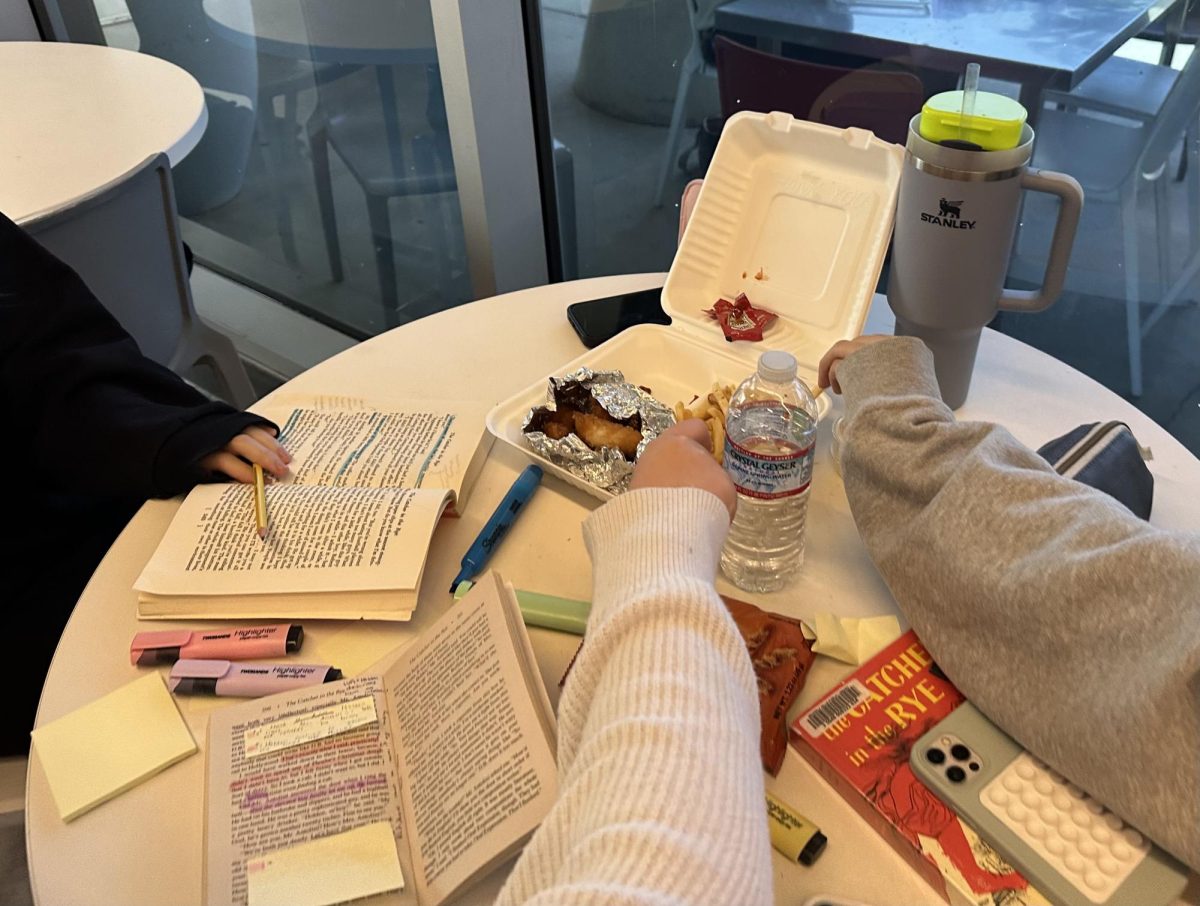

But with most Shalhevet students hooked up to the internet, it’s not uncommon during lunch time for students to harvest cyber-food instead of eating actual food. In class too, it’s not uncommon for students on laptops to switch windows just to check on their farms.

After school, some students grant Farmville more attention than homework.

“I do play when I should be doing homework, but I still pull it off, thank God,” laughed sophomore David Rokah, a Level 44 farmer in possession of a villa, red barn house, and an estate.

“Farmville is just a game that the students of Shalhevet decide to engage in with their spare time,” said Nathan Rivani, a farm-free junior. “My fellow classmates are at a point in their lives where they have to decide how to prioritize. Academically, it might impair them slightly, but it depends on the severity of the addiction for each student.”

The structure of Farmville encourages users to check their farms everyday and give “neighbors” materials to facilitate the expansion of their farms. If users don’t check their farms regularly, their crops eventually wither. Based on this strategy, users stay online longer and become another web traffic statistic, which earns the Farmville developers money, and possibly also fights the youth obesity epidemic by weening America’s teens onto virtual food.

“It is easy to access, you get immediate satisfaction, and because it is played against or with other real people or friends it has a more realistic feeling than simply playing against the computer,” senior Gamliel Kalfa remarked. “I think it is another step further away from good old real interaction and reality.”

Is it possible that Farmville also taps into a basic human drive — to poke and prod an ecosystem to suit your own needs? “I have wanted to start a garden, but [I’ve] never really gotten around to it because I never have the time,” remarked sophomore Maddy Merritt, currently working on a horse stable that would really top off her farm. “But with Farmville, I can access my farm anywhere and show it all over for other people to enjoy.”

In the virtual world, the fuzzy feeling stays, but without muddying up your Nikes or manicure.

“Well, that might be true,” said music teacher Mrs. Joelle Keene, an avid vegetable gardener in the physical world. “You wouldn’t have to deal with squirrels eating your apricots either. But then again, you’d never get to watch a real seedling come up, or enjoy the smell of freshly turned dirt.”

Precisely, perhaps, the point.