Dr. Jerry Friedman and the roots of Shalhevet democracy

If moral development could be taught, why not build a school to teach it?

May 5, 2020

For Dr. Jerry Friedman and his wife, Jean, it all began at their daughter’s graduation from Harvard University. That day, Dr. Friedman — successful Los Angeles real estate developer specializing in industrial warehouses — heard Harvard president Derek Bok call for non-educators to join the field.

Soon he and Mrs. Friedman were studying at Harvard themselves, and especially with Professor Lawrence Kohlberg — a psychologist whose theory of moral development suggested that it could happen in school, with the proper methodology and environment.

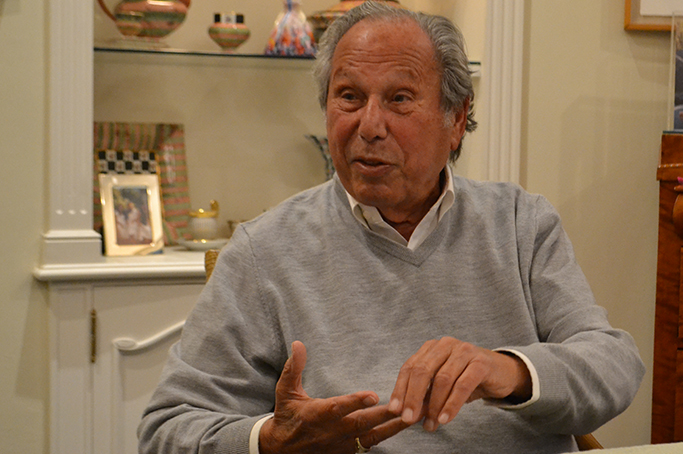

In a two-hour interview Feb. 27, Dr. Friedman told editors of the Boiling Point how what he learned at Harvard got him into Jewish education, and how that led eventually to his founding of Shalhevet.

“Everybody was saying, ‘Well, Jerry, why don’t you start the school?’” said Dr. Friedman. “I said, ‘Are you out of your mind?!’ I mean, I’m a real estate developer!

“Anyhow, I was convinced — or they convinced me – and we started this school, because my concern was all of the research was showing that the Jewish day schools were not doing such a good job as far as developing a mensch— a moral and ethical reasoning human being. So that was the thrust of starting Shalhevet.”

On a cloudy afternoon when school was still open, a crew of Boiling Point staff visited Dr. Friedman in his Beverly Hills home, where after a tour that included rare artwork, sculptures and a 100,000-year-old standing skeleton of a prehistoric bear, they attempted to understand his original goals and philosophy; how Shalhevet has changed for the better and worse in its 28 years of existence; and what he hopes for the future.

Dr. Friedman described how at Harvard, he performed experiments aimed at judging students’ proficiency at moral reasoning. He discovered to his disappointment that students at Jewish schools, which claimed to instill Torah values, were not performing above other students.

“In my pretest — and we had a sample of 149 kids — there was no statistical difference of a kid who went to an Orthodox school, Reform, Conservative or public school at all,” he said.

Using the work of Prof. Kohlberg and others, he said, Dr. Friedman developed a “just community” model for school governance, where students and teachers could vote on as many aspects of the school as possible, from dress code to spaces in parking lots, from running school elections to discipline. That became the basis for the Just Community at Shalhevet.

He described the founding of the school — including a telephone call he had with one of the sons of Rav Joseph Soloveitchik — and how he fought back against resistance to its being co-ed. He also talked about the boundaries of the Just Community and the achievements of Rabbi Segal as head-of-school.

He said the school’s initial vision was for a “direct democracy,” guided by direct votes from the community at Town Hall, led by the Agenda Committee — which he said conflicts with what he called representative or “indirect democracy,” with policies made by elected representatives on the Fairness Committee.

Dr. Friedman now worries that leaving decisions to elected representatives does not force students to make real-world moral decisions for themselves, and therefore does not promote their moral development.

He challenged a suggestion made by some that democratic principles in the Just Community must be sacrificed to accommodate a student body which has grown from 32 students on the day it opened to 258 now.

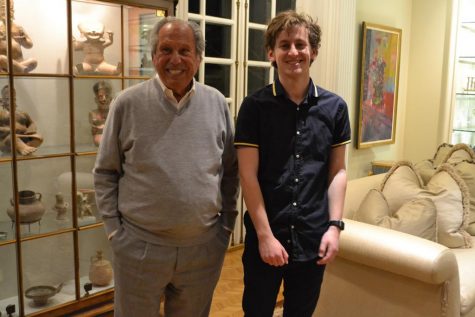

INTERVIEW: Boiling Point Editor-in-Chief Jacob Lefkowitz Brooks, left, posed a wide range over the course of two hours in the breakfast room of Dr. Friedman’s home.

While it can be harder to engage a larger student body, he said, it is the responsibility of the Agenda committee to find creative ways to explain their topics.

“If a school gets larger, as it is now, you just have to come up with some seykhl — some brains,” said Dr. Friedman. “It’s simple. You could say before a Town Hall meeting, the day before, ‘We know the agenda, let’s have a few meetings of 20 students and one teacher each and go over that and get the excitement, because it has to be a hot topic.’ Otherwise students will get bored, and teachers will get bored.”

In a more recent interview, Dr. Friedman also discussed his wife’s role in the founding of the school. It was Mrs. Friedman, he said, who came up with the name “Shalhevet” — a flame that renews itself — rather than a scholar’s name like Rabbi Akiva or Maimonides, other options at the time. He added that she also felt strongly about giving the school a title that was gender-neutral.

“She was a spark plug for me getting involved in Jewish education,” Dr. Friedman said. “Her feeling about Jewish education when she went to Jewish school was very positive. Mine was not. So she always pushed me along, saying ‘It’s good, it’s good.”

But that day at his home, Dr. Friedman emphasized the importance of having students make decisions — real decisions that take effect, as opposed to hypotheticals. This, he said, is absolutely necessary in order to ensure that students learn from the outcomes of their choices, as envisioned in the founding purpose of the school.

PIZZA: As the interview stretched into the early evening hours, Dr. Friedman provided pizza to Boiling Point staff working on photos, video and the interview itself.

“If you’ve developed the rules and regulations and the consequences together, you’re more apt to listen to them, and that’s what the Just Community’s about,” Dr. Friedman said. “As soon as you start taking away from that, then what happens is that you have a good prep school.”

Dr. Friedman and the Boiling Point staff settled into his breakfast room as he shared the details. The interview was conducted by Editor-in-Chief Jacob Joseph Lefkowitz Brooks, videotaped by videographer Vivienne Schlussel and sound engineer Eli Weiss, and photographed by Chief Photo Editor Maia Lefferman.

At the end, Dr. Friedman brought out three Nagila pizzas for the BP crew and invited them to come visit again.

Two weeks later, on-campus school was closed for the Covid-19 pandemic.

In His Own Words

In a two-hour interview at his home Feb. 27, Dr. Jerry Friedman answered questions about Shalhevet’s Just Community past, present and future, posed by Editor-in-Chief Jacob Joseph Lefkowitz Brooks. The transcript below is abridged and lightly edited.

THE ORIGINAL NEED FOR SHALHEVET

The Boiling Point: What was your original idea behind Shalhevet and what was the impetus for you to found the school?

Dr. Jerry Friedman:

Good question. When I was a young kid, I really didn’t like Jewish schools. They were disciplinary and authoritarian. I questioned everything. They didn’t like it. And so forth. Later on, moving the clock forward, actually my daughter went to school and I somehow got to become president of the PTA, and therefore I spent a lot of time in this school and I didn’t like that school, either, that my daughter was going to — a Jewish school. Parents didn’t have anything to say in those days. It was just we know what’s best for your child, period.

Later on Karen graduated UCLA and then went to Harvard. [At her graduation], the president, [Derek] Bok, said he was looking for people who are in science, math and so forth to come into education. And from that I extrapolated why not an accountant, a real estate developer?

So I applied, got in and my daughter always told me about this guy — Larry, Larry Kohlberg, a professor of developmental psychology, a brilliant genius following [Swiss psychologist Jean] Piaget and [American psychologist John] Dewey and so forth. So the bottom line was I enrolled and I found this Professor Kohlberg talking about developmental psychology, a warm, caring atmosphere, a democratic approach, sharing with the staff, going over rules and regulations. And I said “Wow, that could be something.”

So I went back [to Harvard], in order to be sort of a change agent, I didn’t go back to develop a whole school. And what we did is we trained staff in the summertime at Harvard. So we’d do it year after year, training principals and teachers from Jewish schools, Reform, Conservative, Orthodox, they’d come from all over. And then I did it also at UCLA. And what was happening was everybody was saying, “Well, Jerry, why don’t you start a school?” I said, “Are you out of your mind?!” I mean, I’m a real estate developer. Anyhow, I was convinced — or they convinced me — and we started this school. Because my concern was that all of the research was showing that the Jewish day schools were not doing such a good job as far as developing a mensch — a moral and ethical reasoning human being. So that was the thrust of starting Shalhevet.

BP: Seeing that this was your initial vision for the school, how would you say that things have progressed toward where you wanted it to go, and how have things differed from your original vision?

Dr. Friedman: The original vision was to establish a Just Community. When you’re founding a Just Community, you’re really basically saying: I want the students to have mutual respect with the teachers and to develop a warm, caring atmosphere. If you have that atmosphere and have everybody involved in what I would call a participatory democracy. I want all the students involved, because I want them all to grow from wherever they were morally and ethically. So the thrust is that I want to see kids coming out as a mensch. In order to do that, you have to train your staff. Because we used to do this at Harvard and at UCLA. And it took about eight days of training to train the principals and so forth. We began by, again, training the staff.

So we’re talking 25, 26 years ago. And it was an interesting beginning because kids came in from the elementary school, [where] it was sort of a benevolent dictatorship. [At Shalhevet,] when we talked about democracy, they didn’t understand what that means. It meant that I can choose and say something, I mean something. They didn’t get it. At Town Hall meeting they would say, ‘Okay, I [inaudible] What about discussion? What about the minority? The minority, it’s important to hear them out again, and so forth and so forth. So yeah, it went very, very well at the beginning and I really thought we were doing a good job. I don’t know — when I was head of school, we never had a vote that I couldn’t live with, because the school was like the curriculum. The curriculum was a school. So when you had a Town Hall meeting, there was that mutual respect because we developed that atmosphere and everybody, teachers, principals — that we could raise the hand and it was really working

A Town Hall meeting will not work unless you have a warm caring atmosphere and that’s developed within the democratic classroom, of mutual respect. Again, if you don’t have that, it’s not going to work. So any principal, any head of school that has a school like Shalhevet — and we are unique — they have to be able to say: I want to share and I’m strong enough to share development of rules and regulations with the students. It’s mutual — respect each other — and it has to go both ways. So I thought it worked very, very well. I’m not there, so I can’t really answer the other part and say how is it going.

Obviously any new leadership is going to change, but the basics of Kohlbergian approach — and I took sort of the Kohlbergian approach of a Just Community — would stay the same. I love camping. I was waterfront director and I would observe how in the camp, the kids were happy and were learning and they didn’t even know they were. It’s called informal education, as opposed to formal education. I felt Jewish schools were a long, hard day and we should make it as comfortable and warm and caring as we possibly can. So it was working and I’m hoping it’s still working. I really don’t know. I mean I’m on the board and so forth and I certainly support today’s Shalhevet, but you know you ask me that question, you have to be in it.

DR. FRIEDMAN’S RESEARCH AND THE NEED FOR ‘PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY’

BP: Could you explain what the difference is, from an educational philosophy perspective, between a participatory democracy and a representative democracy? Why did every student have to have a say? Why does that matter?

Dr. Friedman: A participatory democracy is important, because if you have a school of 250 students give or take, 260, I want each child, each student, to learn and experience what the Just Community’s about. So what’s different about Shalhevet is in most schools they’ll say, “Okay, in each class you’ll have a representative.” Well, what good is that? Because okay, so a few representatives will perhaps grow. But when you have a Just Community at Town Hall, everybody should advance.

Now why does a Town Hall mean something? It means, in effect, everybody is listening to the moral statements of other students and of teachers and of principals. And when you hear something that’s in a higher moral value continuously, it gives you a feeling of cognitive dissonance, a disequilibrium. It means that that person is saying something, and I don’t feel good about my moral position anymore. That he or she — or the teacher or another student or friend or an enemy — is saying something that I move to a higher madregah [level], to a higher stage of moral, ethical reasoning.

So the real importance of the Town Hall is that everybody is learning, everybody is listening, everybody’s involved. If you notice the ninth-graders that come in — there are some outliers, but most of them really don’t talk much during the first year. It’s only because they’re not used to democracy. They’re not used to listening. There’s a lot you learn when you are in a Just Community. If you’re sitting there, you learn to listen because you’re excited about what’s happening. You’re learning how to articulate a position and finally you get the guts to do it. And that develops your self-image as well.

So therefore, you want a participatory democracy where everybody is involved, and not just a few.

And that’s what makes a school: it develops the atmosphere. Because in that Just Community you’re developing the norms of the school: caring, cheating is wrong, whatever the hot topic is. But you start feeling for one another and what happens to a school, it becomes a community. In our case, a Jewish community, a Zionistic community, a caring community. You start developing norms for the school. You can’t do it by just delegating it because education is not to say, “Hey, here’s the rules and regulations — listen.” Well, they may listen, but it’s reluctant. If you’ve developed the rules and regulations and the consequences together, you’re more apt to listen to them. And that’s what a Just Community’s about. As soon as you start taking away from that, then what happens is that you have a good prep school.

In my research, and that research was really important, I compared kids going to Jewish day schools with kids going to public schools as far as moral and ethical reasoning. And in my pretest, and we had a sample of 149 kids, there was no statistical difference between a kid who went to an Orthodox school, Reform, Conservative or public school. All of these were top schools, and all this was a random sample.

And in fact, the Orthodox came out the lowest — lower than the Conservative, Reform and public school students — and don’t forget this was blind scores. And they had more hours in Jewish learning, so you would think that they would come out the highest — wouldn’t that be the rational outcome? They had so much more in Jewish studies. They would come out the highest — but they came out the lowest. That’s what threw me. I didn’t want to continue. But Larry Kohlberg said, “Don’t you think they would want to know?” And that’s what got me so excited about what we could be doing within the Jewish school system.

Because when we took those kids, we separated them and said here’s a control group where we’re not going to do anything with them. And then I took the experimental group, and for 17 weeks I met with them once a week and created an atmosphere like we have in Shalhevet. After those 17 weeks, the experimental group went up in the stage of moral and ethical reasoning, and the control group was flat. So we showed — we now know — that by creating an atmosphere and environment that’s comfortable for kids to express themselves, while providing cognitive dissonance and disequilibrium so they can hear different levels and ways of thinking that are maybe at a higher madregah [level] than where they are now, we can move a student to a higher state of moral and ethical reasoning. That’s what our problem is with many of the Jewish schools — they’re memorizing ethics and morality but they’re not internalizing it, the process of how to think about this for themselves. And therefore it’s not becoming their way of life internally speaking.

The atmosphere and the way we are doing it at Shalhevet is what we call a participatory democracy — the kids get involved in the process and therefore experience cognitive dissonance — they’re hearing something at a higher madrega than they are at and they start moving in that direction, up. They’re into these moral dilemma discussions and that’s what moves them. Whereas in the U.S. Congress, Congress handles all the moral dilemmas, but at Shalhevet, it’s so much more than just democracy. When the norms go up it’s because they themselves voted on them, not because it was dictated by a teacher or an administrator, not because someone who was elected made the decision for them. The thrust of the Just Community is to share governance. There’s a whole thrust and a purpose behind it. And all of a sudden the norms that have developed at Shalhevet are the norms that they participated in, voting on things, thinking about things, and the school becomes a better school. That’s what makes it work.

So you knew what was happening is our kids — and these are the Jewish schools that I’ve found that I’ve worked with — they are memorizing the Jewish values and they’re smart, but they haven’t internalized those five years of Jewish school. And what happens then is if you give them a hypothetical dilemma or a real life dilemma, you have moral issues conflicted with one another and it’s hard. So when you see that and you see, so then what good is a Jewish school? Except you’re going to become much more intelligent, you’ll know, taller and so forth. But if it’s not in your kishkes [guts] — if you don’t internalize it, then you’re not doing the job.

And if you go to any Jewish school in the country and you go to the principal and say,

‘What are your aims and goals?’ One of the major goals is to develop a mensch? Well, my research says they’re not doing it unfortunately, and I’m sure they’re trying their best.

We found by using this Kohlbergian approach and mixing it with camping — with an informal Jewish education — you create an atmosphere that when you vote for something at a Town Hall, it’s not only your ego voting. It’s saying, ‘Well gee, is this really good for the school?” Because you begin to like the school. You can’t delegate liking the school, you either like it or don’t. And it’s the staff up on top together with the students that create that atmosphere. There has to be that mutual trust and that mutual respect.

SIZE OF THE SCHOOL

BP: It has come up several times that when the school first opened, there were supposedly more teachers relative to the amount of students, as well as fewer students in total. This has been used by some administrators and students as a reason why your method would not be able to work now.

The claim that has been made that now there needs to be more of a representative democracy, to account for the school now being much larger — that teachers proportionally have less of a say in what goes on now, and therefore a direct democracy would be more of a majority rule by the students.

That’s the claim that’s been made. And so I wanted to ask first of all, do you know what that teacher-to-student ratio was?

Dr.Friedman: First of all, we started with 31 students, so we had more students than teachers right from the beginning. So the students could out-vote them anytime. I was head of school for quite a few years and we had 100 to 150 students. So if a school gets larger, as it is now, you just have to come up with some seykhl — some brains. It’s simple. You could say before a Town Hall meeting, the day before, “We know the agenda, let’s have a few meetings of 20 students and one teacher each and go over that and get the excitement.” Because it has to be a hot topic. Otherwise students will get bored, and teachers will get bored.

Yeah, it’s 250 kids and teachers and so forth. So what we did is we did a microcosm. We did a small group, and you gave them the dilemma discussion, the hot topic, whatever we were going for. And then within that group there’s so much difference in the methodology — you could, for example, say, okay, there’ll be one speaker from each one of these groups who will give their position of a pro and con. It gets exciting.

Kohlberg and I drove down together to a school in Scarsdale [New York]. They did a Town Hall meeting where they had a whole skit. They developed the skit on what was going to be talked about. There are many ways of skinning a cat and the bottom line here is very simple: just have a small group. Now in order to do that, the Head of School has to be able to say, “Okay, we’re going to give a half-hour for this to develop.”

BP: Do you think that having a large, successful school with a large student body is in any way opposed to having your vision of a Just Community?

Dr. Friedman: Absolutely not. All you have to do is work it out. Okay, not everybody is going to be able to talk when you have 250 students, but if you have a group of 20, 25 or 30, most of them are going to be able to talk and it’s on the same topic and they’ll get excited by it. Now, who’s going to be the facilitator to get that group? This methodology is not easy; teachers have to be trained continuously. When you have new staff coming in, they might have heard about a Just Community. But they have to understand the methodology for it to work. And new students coming in — if it’s not explained to them and they’re saying, “What’s this Just Community all about? Sounds like a bunch of bull.” But it’s not, because it’s giving you skills.

Besides the ethics and morality, it gives you a feeling of how to articulate and also how to listen. Because in order to be able to challenge that position and also say, “I was so [sure of] my position, you know what? The minority, they have something to say. Let’s give them a little more chance.” So there’s a fairness that comes out, and you start feeling that menschlichkeit, that warmth of a community.

Shalhevet should not be called Shalhevet school; it should be called “Shalhevet community,” if it’s working. If it’s not working, then you’re going to clobber the minority and so forth. But a community will start respecting one another and saying, “I don’t agree with that position, but I respect you the same for it.”

ROLES OF FAIRNESS AND AGENDA COMMITTEES

BP: Recently we’ve seen the Agenda Committee feel like there has been too much of a burden placed on them in terms of their legislative responsibilities, and they’ve asked Fairness to take on some of those responsibilities. We’ve had a few cases about this. Do you think that that is part of Fairness’s jurisdiction, to decide policy?

Dr. Friedman: No, because if you recall the questions at the beginning, we talked about wanting a participatory democracy. The Fairness Committee is a small group. That’s, in effect, taking away the authority and sort of making Shalhevet a representative democracy, where only a few kids would get the advantage of that. Rules and regulations should be [initiated] in the Agenda Committee. The Agenda Committee is the most important to me. No question.

The Fairness Committee has another position, another job to do. If a teacher and the students have a problem, if two students have a problem, they can’t resolve it or something on grades, or I may have caught you cheating, and you can’t get agreement, you’d go to the Fairness Committee. That’s their position, that their raison d’être [reason for being]. So, have you read our constitution?

BP: I have.

Dr. Friedman: It’s a very interesting constitution. You have a Fairness Committee, you have the Agenda Committee and you have the CCC, the [now inactive] Constructive Consequences Committee. That’s another committee for consequences and so forth. But the Fairness Committee is different. And the Agenda Committee, if it has a load — which I can’t even understand that — but they could say, okay, I want to delegate out, because that’s what most committees do. We have a chair, the chair can’t do everything. And say, “Well you can take care of writing this material down, you investigate that,” and so forth. So the Agenda Committee can broaden itself… [or] you can take a Town Hall meeting and rotate the chairs.

A Town Hall will not function, in my estimation, unless there’s an atmosphere of warmth and caring and mutual trust. There’s plenty of schools that will have Town Halls that are meaningless, because there’s a fear of what you say. Will somebody take advantage of you? Will a teacher or principal? If the warmth and caring is there, and mutual respect and mutual trust is developed and that’s the environment and atmosphere, and that’s how it’s done through this Town Hall meeting, saying: “Hey, that teacher, she agreed with me and the other teacher disagreed with that teacher. Wow, this is fairness. This is democracy. This is real.”

But if you start manipulating that and taking things away from it, then you will see. You can call it a Just Community. It’s not. It will fade away and the community will suffer, but you wouldn’t even know it. It’ll slip. So you have to have a staff and you have to have a student body that wants to work together, and the staff, it has to feel very secure. Otherwise they would get into this kind of situation.

BP: Talking about that, the majority of issues in which Fairness has decided to make a policy have been instances in which a faculty member has taken the entire student body to Fairness. One example that was just resolved last week was when a teacher observed that there was vandalism — students leaving trash, writing on posters in classrooms, around the school. This teacher took the entire student body to Fairness and then Fairness ultimately made a policy saying that teachers were allowed to lock their doors during non-class periods and then students could not go into those rooms.

Do you think that if this was something that Fairness should’ve decided, and if not, how could this issue have been resolved?

Dr. Friedman: Okay. The Fairness Committee and the Agenda Committee. They should be working together. If the Fairness Committee takes on the whole school, I would suggest the Fairness Committee brings it to the Agenda Committee and it goes to Town Hall — because the Town Hall, again, it’s the key. It makes it function and says it’s fair, it’s just. I would like the students and teachers to discuss and say, “Hey there’s vandalism here. What kind of school is this? What kind of community are we? Are we stealing from one another? We shouldn’t be doing that. It’s terrible.” So this is a perfect learning experience for a Town Hall.

You know, you never can tell what should come up. But the Fairness Committee and the Agenda Committee and any other committee should be all working together, and meeting at a regular time and working it out together.

But a Fairness Committee in my mind should be much more a one-on-one or one-to-three. See, there’s a learning experience. Yeah, you can say, “Okay, Fairness Committee do it,” but it’s not the wise thing to do. Really the wise thing to do is let the Agenda committee call the Town Hall and say, “This is a situation.” And what a learning experience! Creating cognitive dissonance, disequilibrium, not feeling good about it. Is it fair that you vandalize a teacher’s room and just whatever the case may be, it’s not right.

When a school makes a rule and regulation, it should be the whole community making it. Because then we’re more apt to listen to it, to obey it. If it’s coming down from on high, I either don’t want to buy into it or I don’t understand it. When it gets into the total community, they’ll be able to understand it. That they may not agree with the answer, but they’re part of the decision=making process and they feel more apt to obey it that way.

BP: In your Just Community model, how should it be dealt with if one group, which in this case seems to be the teachers, feels wronged and that the entire community is not listening to their concerns — even if it were to be brought up in Town Halls? If a policy were to be voted on and this vandalism was going to continue to occur, how should that have been dealt with?

Dr. Friedman: I think and I believe that the Shalhevet community should deal with it. It’s a terrible thing when within a community one is vandalizing. It is something therefore not for any subcommittee, not for any head of school. It’s for the community to decide: how do we work this out?

Look, if you think that’s a problem, in the old days, drugs were the big problem. And so Kohlberg developed a school [not Shalhevet] and they had problems with drugs. This was not a neighborhood like a Jewish school. And they had these problems and they would say you can’t come to school all high and so forth. And [the student would] say, “Well why not?” He said, “Because you’re disrupting some of the other students in the class.” So they gave [that student] a few opportunities and finally they decided as a community that he shouldn’t be in that school.

Well, it’s the same thing, what you’re looking at here. Vandalism? To steal from your own friends, from your own staff. There’s something then wrong with the community, because for 20 teachers or 10 teachers or the one teacher to say we are “we-against-them” — the whole thrust of the Just Community was not to have the teachers and staff against the students. It was “we are a community and we’re working together for the best of Shalhevet.” What you’re telling me — I don’t know anything more about what you’re telling me — is there’s something wrong with the atmosphere, the environment of the community.

The community should tackle that together and say there’s a break in the community, and that’s a slippery slope. Once you start moving away from the community [Town Hall] to go into rules and regulations, and you give it to Fairness or whatever committee, it’s a slippery slope. It keeps going, and then you get to an authoritarian school, you get to a prep school like any other school. And that wouldn’t be what I wanted to have.

BP: If there is an instance in which the student body passes a rule, a piece of legislation in Town Hall, and then they proceed not to follow that after a certain amount of time. What is the mechanism to deal with that?

Dr. Friedman: In your constitution, you have the [former] consequence committee, right? It should probably go to a Fairness Committee. It could go to Agenda Committee and then they say, well, what are the consequences for disobeying the rules or regulations that you’ve developed, and that should be approved according to how severe it is. Maybe you want to get back to the whole student body and say “Can we resolve this? We’re not looking to do the consequences but we can’t accept this.” Because every society has to develop some rules and regulations. You don’t obey them, there have to be consequences. So I’d probably have the consequence committee if you have one now.

BP: We don’t currently. Do you think that can fall in the realm of Fairness?

Dr. Friedman: No, it shouldn’t. It should be separate. That’s why we had a CCC. We had a consequence committee that they would have that. But there should be a movement among the committees and it shouldn’t be like each one is isolated. The Agenda Committee should be the one saying “Fairness Committee, let’s have the chairs meet at least.” Or let’s have a few of us meet. But that should be happening. Because you can’t work in isolation.

If you have a problem that you can’t resolve, then say: “I want to speak to the head of school, let’s get together and see how we could resolve it.” That’s a community. Otherwise you have Russia and China and you know, that’s not what we’re looking for. We’re looking for shalom bayit [domestic harmony].

ABOUT TOWN HALL…

BP: Currently the vast majority of Town Halls are dedicated towards moral dilemmas, like discussing a current event or an emerging trend in society and then letting people talk about it. Do you think that Town Hall is a place for these moral dilemmas or should it be exclusively for proposals?

Dr. Friedman: Well, the Just Community and the Town Hall, there should be rules and regulations that should be developed over there. If everything is perfect— and I doubt in any institution there’s anything perfect — then you can say, “Well, there’s something that’s come up in the community that we want to discuss.” That’s fair, if it’s a hot topic for the students and they want to do it.

The chair for that Town Hall should be a mature adult and probably should have some training, because that’s a difficult thing for a teacher to handle, for a principal to handle. And all of a sudden we’re asking that skill of an individual student, a senior, and saying, “How does he handle this? Does he act as a facilitator? Does he take a side?” There’s a training that we train staff, teachers and principals, and it seems to be perhaps throwing somebody to the wolves and saying, “Okay, learn as you go.” But that’s an expensive thing because you have 250 students that are looking at you.

I’ve gone into Town Hall meetings from time to time and I’ve seen the chair taking a side. Well that stopped a lot of students from opening their mouths, because they’re in such awe, especially a ninth-grader or 10th-grader, of the head. So you have to be a facilitator. You don’t take sides. You have to get everybody to speak. And especially the minority, because they’re a little scared. Everybody’s against them. So now you have to pull them out and say, “Hey, that’s freedom of speech. That’s what we’re all about. To be able to be kind and caring for each other.”

BP: Seeing that you said that ideally students would bring their concerns in the form of proposals, there have only been two proposals this year, neither of them very major. Do you think that the Agenda Committee and the Agenda Chair should be encouraging students to write more proposals?

Dr. Friedman: Oh yeah. I think that it should come not only from the student body, but from the staff. We’re one community. We’re not two communities. That’s a whole thrust of the Just Community. So we should be getting whatever is exciting in a hot topic because you want to keep everybody involved with what’s going on.

If you get something that’s boring, it’s sort of like if you give it to a dilemma discussion and they see the dilemma, nobody’s interested in it. So if you’re wise, drop that dilemma, get into another good dilemma that’s exciting. It’s up to the Agenda Committee to say “Where are the hot topics? What’s going to be interesting?: Otherwise it’s going to be boring and teachers are going to be bored and students are going to be bored.

We’re human beings. You’ve got to make it exciting, and one has to be able to say ‘What’s a topic?” If it’s stealing, if it’s parking, if it’s uniforms. There are so many topics there. And most of these topics by the way are dilemmas. Because I remember we had it with the students. They wanted to park and the teacher says, “Hell, we want to park.” And the students would say, “Why do you think you’re so special?” And then we would say, “Well they are the adults and they have to go in and out,” and so forth. So you can resolve it because of that. Or you can say, well maybe we have something to say. Maybe we should give three spots to the teachers or one spot. There’s a compromise. That’s what life is about.

BP: So do you think that the impetus for discussions about issues going on in the school should come from students writing proposals or from Agenda? Identifying topics which could be interesting to students and then encouraging proposals after.

Dr. Friedman: I think all the proposals should come in from the students, from the teachers, and then the Agenda chairs should be wise enough to say, ‘This is boring. There’s nothing here, there’s nothing that’s gonna be exciting,” or “This one we can tighten up and we can really make it.”

BP: It just seems to be the issue right now is that people aren’t very interested in writing proposals. And as you said, if you walk around the school, you’ll hear a lot of people complaining about things going on, but no one seems to want to go out of their way to write proposals. And then Agenda responds with, “Oh, no one wants to write proposals, so let’s just have a discussion about artificial intelligence.”

Dr. Friedman: Let’s say I’m the agenda chair. Let’s say there’s five or eight members. Go out, send each member out to interview students. They’re too lazy to write it down? I’ll take it down. I’ll go and ask them: :What’s bothering you? Do you love the school?” “Yeah, I love the school, but…” But what? Grab it.

So innovate. If they’ve got exams on their mind, they’ve got homework on their mind, this doesn’t come to the top. So Agenda, go out there and bring back two proposals, each one of you, and then we’ll choose what we want.

THE ROLE OF THE ADMINISTRATION

BP: The administration has recently said that they feel they need to have a say in the passing of proposals. It’s not in the constitution and it’s been kind of ambiguous what exactly this role is. At times it’s manifested itself as a veto that’s been made by the head of school, and at other times it’s been simply the faculty advisers on Agenda, who have said, “We don’t want to talk about this proposal because we feel it isn’t right for discussion.” And I would like to add that the constitution does provide three realms within which, no proposal can be made and all, which is Halakha, state law and pedagogy —

Dr. Friedman: But you can discuss them and not vote on them. Statutory law, Halakah — you can discuss it, but you have every right to say we should have school two hours a day and that’s it. So those are discussions you can have, but you cannot vote on.

BP: Who do you think should be making the decision of whether proposals venture into those realms?

Dr. Friedman Well, we also had a committee way back. A legal committee sort of. And it said, in effect, let’s look at the constitution. What can we do? What I remember also, when we met [with David Edwards, Evan Rubel, Sabrina Jahan and other community members] for the constitution — we discussed it about a year ago — we said the atmosphere and environment of a Just Community should not be antagonistic. It should be going to the head of school or whoever it is and say, “Hey, let’s discuss this.”

There’s a vote. An Agenda Committee has two staff members on it. They’re not the majority. That’s why you have the students there as well. There will be a breakdown of the Just Community if you have now the administration saying, ‘Hey, I veto this, I veto that,” and so forth. The atmosphere has gone, the environment has gone.

So there has to be a [system] where we have to sit down with the head of school, whoever is on the Fairness Committee, Agenda, the staff, and say, “What’s the problem? Let’s see how we can get around it.” If you’re saying that we as students haven’t got the maturity and do these things and you have to do it, then we don’t have a Just Community and you go authoritarian, hey, you can do it. I’m sure there’s top prep schools that are very authoritarian and they look fantastic on the outside. The problem is with an authoritarian school, you don’t develop the ethics, the morality, the menschlichkeit. When you will develop somebody in math and science and so forth, I say you can do all that within a Just Community and more. But soon as the administration or a teacher feels like “I have a final say,” then the whole system’s broken. The whole atmosphere goes. It’s no more Just Community.

BP: Talking specifically about Halakha, how do you think that that should be determined? What Halakhic rules is the school going to say that proposals can venture into?

Dr. Friedman: That I think goes to the head of the school. What we did at the beginning, because I wasn’t a rabbi, we used Beth Jacob, because they were very supportive of us to develop the script because we had a co-ed school. This was a big no-no. So any time we had a Halakhic question we’d go there.

Now if you have a rabbi, so Rabbi Segal would be making those a lot of decisions, but they have to be based on the Halakha. And again, it should be discussed. I mean one can disagree but then say, “Okay, let’s bring in three other rabbis,” or whatever it is. But it shouldn’t be, again, a conflict that can’t be resolved. There’s a compromise.

“…If it’s getting to [a point of] tension, then there’s something wrong. There’s a breakdown of the community and there should be some staff getting together with leaders of the student body and saying let’s work this out, because that sounds like just one indication of perhaps other things that are happening.

A NEW CONSTITUTION?

BP: We recently began a constitutional convention, which was started by a few seniors. There haven’t been any meetings in a while. Do you think that the Just Community needs a constitution in order to function?

Dr. Friedman: A constitution, in effect, says what are the rules and regulations and what are the aims and goals of this school, this community. Yeah, I think so because it’s something you go back to. That constitution, a lot of work went into it. And at that time it looked like it was a right thing.

Now if you read it, you’re not following it from a point that the committees are not there, the reports are not there, I’m not sure the handbook is there and so forth. So there’s been, again, a slippery slope down and that’s a very dangerous thing in any business. So one has to say, “I want to bring it back.” If they want to amend the constitution, yeah, that’s democracy.

If something is breaking, then it’s the leadership of the students to get together with the leadership of the staff, the faculty administration and say, “This is not working. We’re having problems. How do we resolve it?” The key to a Just Community is sharing governance. If you don’t share governance, then okay, you don’t have a Just Community. You can call it whatever you want, but it certainly is not a Just Community. A Just Community, the key to it, is sharing rules and regulations. Developing them together.

BP: Do you think that having a constitution — which has imbued those values in students and yet isn’t exactly binding, seeing that there are so many things that don’t reflect the current state of Shalhevet — do you think that that takes away from people’s ability to function in the Just Community? Or do you think they’re still able to?

Dr. Friedman: First of all, you have to tell me what you’re not abiding to. If you’re not talking about a committee or so forth, but the thrust of sharing governance, that’s the heart of the Just Community — meaning that the students and the staff vote on rules and regulations.

BP: Do you think that there is a need to update the constitution? If there’s still is the basic tenants of it in the school?

Dr. Friedman: As far as I’m concerned, the constitution is reflecting what we wanted and we thought would be good. Now every 10 years there’s a new generation and new ideas and new thoughts. But one would have to be able to say, what can you do to make it better? And if there’s something there, that’s why you have an amendment. That’s the process. And I’ll tell you — sometimes the process is more important than the rules.

DR. FRIEDMAN’S LEGACY

BP: Could you tell us something about the school that you see after 25 years, and after you have not been head of school for about 10 years? Something that you still love, that you see your legacy, that’s thriving.

Dr. Friedman: Oh yeah. That I could easily say. I shep nachus — that means I get a lot of joy — when parents come over to me or when former students come over and just say what an impact this school has had on them. And the latest one was when I was in Israel recently and someone came over to me and said, Dr. Friedman, “Do you remember me? I was with the — and you changed my life.” That’s heavy stuff. She continued and said “I so enjoyed Shalhevet. It was such a wonderful institution. The whole theory of sharing with the students and the teachers — I love it. And you know, when I was there, there was an opening at the end for Bnei Akiva camp… and I went to camp there and I want to introduce you to my husband, who I met at camp. So you changed my life.” Because of her meeting her husband-to-be. Because if she hadn’t been at Shalhevet, she wouldn’t have applied to Bnei Akiva camp. I get so many students coming over regularly and that’s the biggest joy I can get. Frankly, many of them I don’t recognize. They’ve matured. But that someone would come over and introduce me to their husband and to their kids.

People say, “You gave about 17 years to this developing, you gave up your whole real estate.” I said, “You know, so?” I was so lucky, so fortunate to be able to do that. And by the way, when you go into a school and you get involved, you don’t make only friends, you make enemies. There’s always something out there. Whether it’s jealousy, it’s human nature, it’s something, but you get clobbered by that as well. But at the end of it, to see the students coming over and parents saying, “You changed my kid’s life,” it gives me a lot of joy.

And again, I was very fortunate to be able to be in the right place at the right time, to go back to school at 55 years of age. I never planned, when I went back to Harvard — I wanted to be a changer, because I thought Jewish education wasn’t going in the right direction. I knew that, but I also knew that if I didn’t have the degree, these credentials, you really don’t have too much of a say within education, because they look at that. And I think I was looking at it in both careers — real estate and education.

The only regret I have is that other Jewish schools haven’t emulated what we’ve done. I can’t understand it. It’s so important to have kids involved in rules and regulations so that they feel part of the process. You can’t be a dictator to a child, to a teenager. If you involve them, then they’re going to be happy with it. If you have a dictatorship, there’ll be there, but they’re not there really all the way and they don’t develop. And the aim of education is developmental, and we may be developing in science and math and so forth, but they’re not developing their neshama [soul] or that environment we create at Shalhevet.

Each head-of-school is going to do it a little differently, but as long as they keep sharing that governance, that’s going to be good. And the problems you have will always be there because human nature is going to say, “Hey, we are educated, principals, teachers and so forth. We know what’s best.” So it’s very hard then to share.

But when I hired staff, they could be the best science teacher, math teacher. If they didn’t have that feeling of real security that they could take a kid, say “I don’t agree with you,” without killing them, they didn’t come to work at our school.

BP: I just wanted to ask if you had anything else you wanted to add?

Dr. Friedman: I think you gave a very excellent interview. I wasn’t prepared for you, but I think I really enjoyed doing it and let’s do it again.