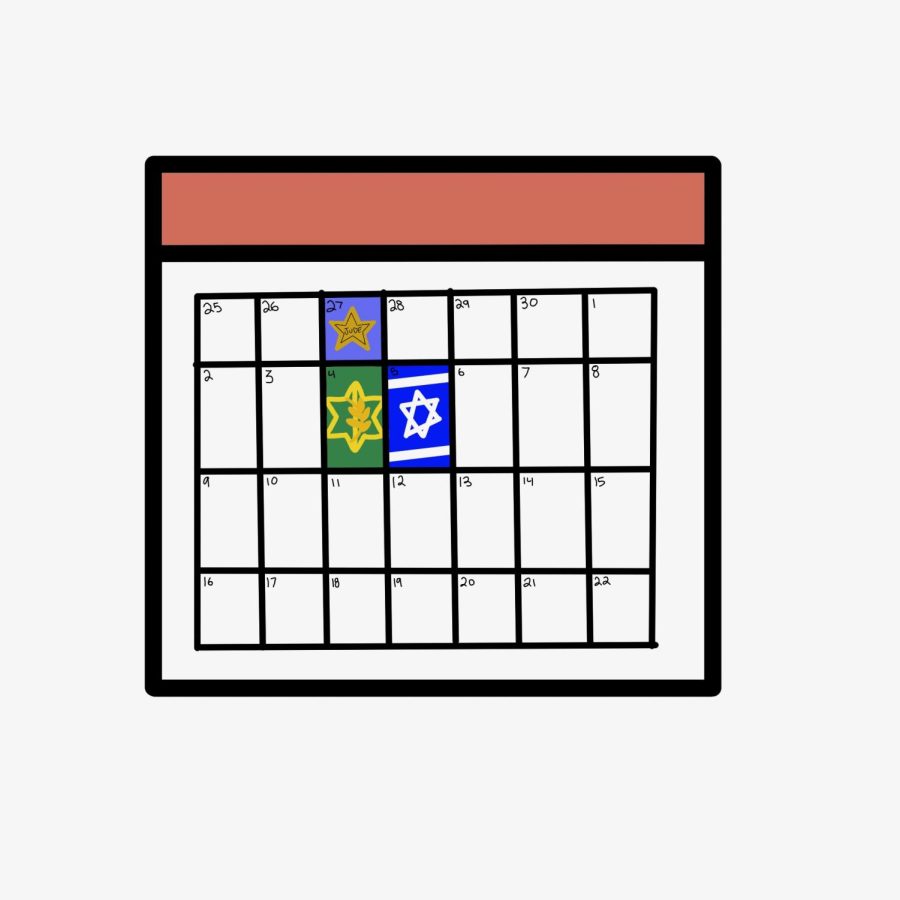

CALENDAR: Every year, Yom Hashoah is followed a week later by Yom HaZikaron, a remembrance day for soldiers and victims of terror, which is then followed by Israeli Independence Day one day later.

Three days that remember a century: Yom HaShoah, Yom HaZikaron, Yom HaAtzmaut

Remembering a particular time in timeless halacha

For the Jewish world, the 20th century was incredibly dynamic and Jewish life changed fundamentally. Out of everything that happened, two events stand out in particular: the Holocaust and the founding of Israel.

Such significant events had to be commemorated. Therefore, many Jewish communities around the world have instituted Yom Hashoah, commemorating the Holocaust, and Yom Ha’atzmaut, celebrating Israeli independence.

Still, for decades and even until the present day, many rabbis have opposed these additions to the Jewish calendar. The path to establishing them was met with debate. And though they both now are widely accepted among Jewish communities, major rabbis opposed the addition of new days in the Jewish calendar along the way.

For example, in April of 1951, the Israeli Knesset decided to commemorate Yom Hashoah on the 27th of Nissan, which marks the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. Then in 1977, Rav Soloveitchik asked Prime Minister Menachem Begin to remove Yom Hashoah from the 27th of Nissan and incorporate mourning the Holocaust into Tisha B’Av – citing one of the medieval kinot (elegies) which states that instead of adding a new day of mourning, the practice is for Jews to commemorate tragedies on fast days already instituted. The Shulchan Aruch also explains that since the expulsion from Israel, the Jewish community can lo longer institute another fast.

At Shalhevet and elsewhere, although we observe Yom Hashoah, we do not commemorate it in the same way as a fast day such as Tisha B’av, and thus incorporating the opinions of Rav Soloveitchik and many others into our manner of observance. As Modern Orthodox Jews, we realize that even if we cannot assign a fast day to Yom Hashoah, we can create innovative and unique ways to commemorate this singular and recent event in our history.

One such way is the memorial service which takes place in many Modern Orthodox shuls. It is common that such services include personal stories, many of which relate to the shul or its congregants and their family history. The renowned Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, z”l, created a prayer for the day.

Yom Hashoah also teaches us about the difference between festive days and solemn days in the Jewish calendar. For a day commemorating a tragedy, certain additional prayers are added to daily davening and a fast is instituted, whereas the quintessential aspect of a festival is the presence of Hallel. Hallel is added only when celebrating things that happen in Eretz Yisrael – so for example, Hallel is said on Hanukkah, which describes a miracle in the Holy Temple, and not on Purim, which celebrates events in Persia.

This distinction is described in a gemara in Masechet Arachin. This Gemara focuses on Israel because returning to Israel would be the greatest miracle for the Jews living in the diasporic world after the destruction of the Beit Hamikdash. Correspondingly, to a Jew living in Eretz Yisrael in the time of the Beit Hamikdash, the greatest tragedy to either an individual or the nation would be expulsion or exile – the date of which, Tisha B’Av, is then commemorated as a fast day.

So in many communities, Hallel is said on Yom Ha’atzmaut. Some rabbis oppose saying Hallel on Yom Ha’atzmaut because it would be saying Hallel too much, though there are many more religious sources supporting adding future Hallel services. And an even more common reason for rabbis and communities to oppose Hallel on Yom Ha’atzmaut is some do not even consider the founding of Israel to be a miracle, in which case there would be no case for Hallel at all.

Most American and Israeli Jews do, however, consider it a miracle, and Shalhevet as a school does too, hence our in-school observances of all three of the yoms. And every year during the stretch between Yom Hashoah and Yom Ha’atzmaut, I can’t help but notice the intentional narrative.

The trio of days of commemoration – including Yom Hazikaron, which commemorates the fallen soldiers and victims of terrorist attacks – together reminds us of the atrocities committed against us and why we need a Jewish state; then shows us the sacrifice and martyrdom of men and women to ensure our nation’s prosperity as we mourn the fallen; and lastly, the celebration and love for the thriving Jewish state we have today in Israel.

The arrangement of these days portrays the suffering and miracles of the 20th century, in a way which can remind all of us of a story or path towards redemption – a goal that is both ancient and new at the same time.