OUT OF THE SHADOWS: Ancient tradition meets modern sensibility

June 3, 2015

With society’s increasingly tolerant attitudes towards rights for gays, lesbians, bisexuals and those who are changing genders, Modern Orthodox rabbis have been grappling with the role of LGBT Jews within the community in light of halachic proscriptions against homosexual acts.

Most Modern Orthodox rabbis say that homosexual Jews can have any role they want within the faith, and should be treated like any other Jew.

But the questions don’t seem to end there. For LGBT Jews who are religiously observant and want to live halachic lives, the halachic prohibition itself presents a problem. Without answers, they have difficulty maintaining their faith and religiosity.

“There was a long time in which I had a complicated relationship with prayer and with God and with Judaism as a whole because it seemed to me like there wasn’t a place for me in Judaism,” said Shalhevet alumna Jenny Newman ‘11. “I’m queer, which makes it kind of questionable that I should be able to exist according to Jewish law.”

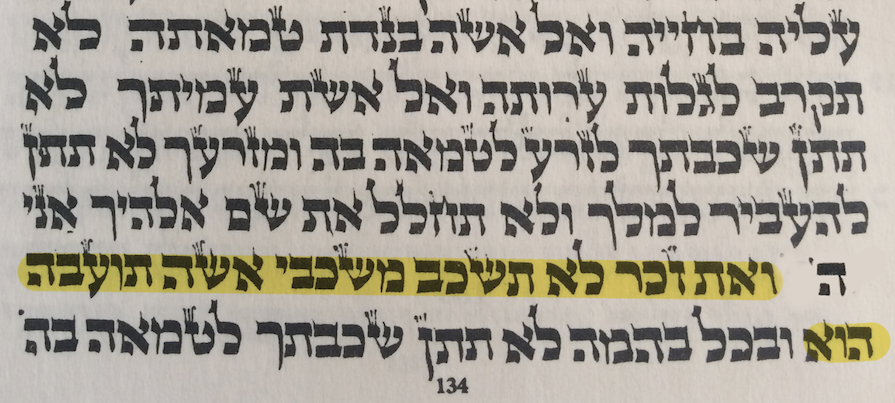

The halacha in question is based on the verse in Vayikra, Chapter 18, verse 22, that says: “You shall not lie down with a male as with a woman: this is an abomination.”

Rabbis at Shalhevet and in the Pico-Robertson community agree that the prohibition seems clear.

“In my opinion, one cannot deny that the Jewish law prohibits homosexual relations,” said Rabbi Kalman Topp of Beth Jacob Congregation in Beverly Hills. “A sexual relationship, according to Jewish tradition, needs to be in the context of marriage and is between a man and a woman.”

Shalhevet Talmud teacher Rabbi David Stein differentiated between the Torah prohibition against homosexual acts with being gay, which he said in and of itself is not proscribed.

“It is not prohibited to be gay, but Judaism does articulate a prohibition against certain homosexual acts,” said Rabbi Stein. “There’s nothing really to dispute about the fact that there exists a prohibition against homosexual sexual conduct.”

Rabbi Yosef Kanefsky of Bnai David-Judea Congregation said this sets up a tension between competing values.

“As the Orthodox community we are right now caught between two values that are of the utmost importance to us,” said Rabbi Kanefsky. “One value is upholding and respecting the dignity of every member of our community, and the other is upholding and respecting the halachic tradition that we have received.”

“Halacha does not permit homosexual sex, it simply doesn’t,” Rabbi Kanefsky said. “We simply don’t have the authority to undo thousands of years of halachic history and precedent.”

But for religious Jews who find themselves in these categories, this view is not obvious at all. Jenny, a senior at American University who announced being lesbian on Facebook last Oct. 11, sees many different ways to read the verse.

“The Hebrew can actually be interpreted several ways,” said Jenny, who is still observant and considers herself Modern Orthodox. One, she said, is that a man should not lie with another man in the same bed as a woman, at the same temporal location (i.e. threesomes).

“Or it could mean that a man cannot have sex with another man while married,” said Jenny. “That homosexual acts are not excused from the general, much more pressing edict against adultery. That last one seems more logical to me – especially since nothing about queer sexuality is vilified or discussed at any other point.”

That view, it turns out, was also suggested by Rav Judah HaChassid, the 12th-century Italian kabbalist and author of Sefer HaChassid, according to Rabbi Kanefsky.

“In that sense [it] has validity as interpretation, or precedent as interpretation of the prohibition,” he said. “At the same time, it does not change the prohibition.”

This is because of the way that halachic processing works, Rabbi Kanefsky said.

“In halachic processing, the connection between the reason for a law and the actual parameters for the law is not so exact,” said Rabbi Kanefsky. “The prohibition comes in absolute terms even though the reason only applies in certain circumstances.”

Like Jenny, openly gay Rabbi Steven Greenberg of the Shalom Hartman Institute also says Judaism permits homosexuality. He believes the Torah does not commit to a single interpretation of a verse, but rather each verse is viewed in the context of other verses, the situation and human reality.

Rabbi Greenberg uses another verse, Devarim Chapter 27, verse 21, to support his view. That verse states: “Cursed be he who lies with any animal. And all the people shall say, ‘Amen!’”

The chapter contains identical curses for many other prohibited sexual relations, but does not mention homosexuality at all. According to Rabbi Greenberg, this means the text is cursing only violent, nonconsensual sexual acts.

“The reason Torah doesn’t mention sex with a male, in all the curses here, is that … it’s not about violence and violent sexual encounter [that] call[s] forth screaming from the victim,” said Rabbi Greenberg. “What the Torah calls for death, is not for a relationship between two men.”

Rabbi Kanefsky said that interpretation does not change the prohibition either.

“Whereas Rabbi Greenberg certainly has a right, the interpretive right, to suggest that what the Torah is forbidding is violent or nonconsensual homosexual sex, a, it’s not clear that’s true from the context, and b., this hasn’t been the way the verse has been interpreted through thousands of years of interpretation,” Rabbi Kanefsky said.

Despite the differences of opinion on the Halacha, everyone interviewed by the Boiling Point agreed with Jenny that there is room for LGBTs in Judaism, and that they should be treated like everybody else.

“I think that they do have a place in the Orthodox community, in the Jewish world,” said Rabbi Topp. “I would encourage them to observe the other mitzvot.”

Both Rabbi Topp and Rabbi Kanefsky would allow LGBT Jews to be members of their shuls, to be counted in a minyan, to receive aliyot, and to participate in all of the shul’s spiritual activities.

Not only do LGBTs have a place in Judaism, but both Rabbi Topp and Rabbi Kanefsky tell others to treat LGBT with dignity and respect.

“It does not matter who someone is, the obligation to engage with people in a dignified way and work towards their inclusion in the community is independently important,” said Rabbi Kanefsky.

Jenny Newman would like Orthodox communities to go a step further, accepting transgender Jews as well and viewing them as they see themselves.

“We need to accept trans men and women as simply men and women…,” said Jenny. “A person’s religion should be something that brings them love and respect, not just one more arena where they have to experience fear and shame and hide who they are.”

That question seemed to stump the community rabbis. Rabbi Topp declined to comment on whether or not a transgender man could be counted towards a minyan. Rabbi Kanefsky said he didn’t know.

All of the rabbis interviewed by the Boiling Point agreed that the fundamental rules of Judaism apply to all Jews. That included Rabbi Judah Mischel, a frequent guest teacher at Shalhevet who is known as “Rav Judah” at school.

“We don’t have application forms or qualification requirements to be part of the Jewish community,” said Rav Judah in a telephone interview. “A Jew is a Jew. And as far as a person’s lifestyle, orientation or disposition, what they’re struggling with in their private life, Hashem is the Judge.”

The law in Vayikra, Rav Judah said, can sound “very harsh, and it can sound very absolute.”

“We have to find a balance,” he said, “and be empathetic and sensitive and also stay true to our moral code and to what we understand to be divinely established norms.”

Most importantly, the Torah’s laws concerning prohibited sexual relations are not the only laws involved.

“In a healthy, God-centric community there is no room for self-righteousness, ignorance or intolerance,” said Rav Judah. “The fundamental principle of the Torah is v’ahavta lere’echa kamocha — you should love your neighbor as yourself.”

These stories won Second Prize, Boris Smolar Award for Enterprise/Investigative Reporting, among papers with circulation 14,999 and lower in the 2015 Simon Rockower Awards, sponsored by the American Jewish Press Association.

Jenny Newman ’11: Coming out

Many Jews at Shalhevet and around the world struggle with Judaism and connecting to God. But for one Shalhevet alumna, the path has been even harder.

Shalhevet graduate Jenny Newman is a lesbian, though she refers to herself as “queer.” A senior at American University who will attend Georgetown University Law School next fall, Jenny has worked hard to reconcile the tension between her faith and her sexual orientation.

“The problem is that Judaism doesn’t have a perspective on homosexuality,” said Jenny in an interview. “I knew that it would be something that distanced me from my peers and my history and my culture, because the Jewish Modern Orthodox culture had struggled with accepting its homosexual congregants.”

As a high school student, Jenny recognized that she was not straight but was unsure of her sexual orientation. Shalhevet’s sex education lectures never touched on it.

Active in Mock Trial, she also wrote and performed in plays, and played flute in the chamber orchestra. But her fellow students made comments that were hurtful.

“My classmates at Shalhevet thought spreading the rumor that I was a lesbian was one of the most insulting things they could come up with,” Jenny said. “People were making snide comments about me taking a girl to prom, and how that would be something I would totally do — and God forbid a lesbian show up at prom.”

“I was incredibly terrified that I wouldn’t be able to find any level of acceptance from my peers, and from my former teachers, who have all at some point said some pretty, not offensive, but generally ignorant things about homosexuality.”

Only in college did she learn to embrace her sexuality. During her freshman year at A.U., she confided to her friends and family that she was gay.

“Everything suddenly became a lot less complicated,” Jenny said. “It became a lot easier to be who I was without worrying that people were gonna judge me for it or assume some things about me. It made existing feel like it was suddenly a lot less burdensome.”

Last year, she came out on Facebook — on National Coming Out Day, Oct. 11. To her surprise, Jenny’s Shalhevet classmates were more tolerant than she had feared.

“The last people I came out to were the close circle of friends I had in high school,” Jenny said. “It was a lot less stressful than I thought it would be.”

Jenny is still religious, and considers herself Modern Orthodox. Even though Jewish laws can be construed to prohibit homosexuality, Jenny maintains her own interpretation of the laws.

“I’ve heard laws about homosexuality interpreted in many different ways — the most sensical of which is that the edict against homosexuality serves more as a reminder that one can’t commit adultery even if it’s with someone who’s a member of the same sex.”

Jenny has also considered homosexuality within the context of other prohibitions in the Torah.

“The laws far and above discuss things like cruelty to animals as being abhorrent, discuss things like causing people embarrassment to be abhorrent,” she said.

Her belief about the law stems from her conviction that God cannot hate her.

“If Hashem could truly hate any person that He is responsible for, simply on the merits of who they are, then I give up, and I can’t believe that of the universe, and so I don’t,” said Jenny. “I can’t wrap my mind around the conceptualization that there is something broken about me fundamentally because of who I am and so I have decided that that can’t be a thing.”

And so she has stayed religious.

“I would still consider myself to be Modern Orthodox,” said Jenny. “I am fairly openly Jewish, I keep kosher. I maintain a fairly regular schedule of praying on my own.”

Shalhevet, she said, was not too helpful in her struggle.

“Shalhevet never really talks about what it means to be gay, or even bisexual, or to be transsexual, and it’s as though that doesn’t even exist,” said Jenny. “It’s always going to be hard when most of the people around you treat your right to marry someone you love and build a family together as a matter of debate, as though you’re less of a person, less of a citizen, than they are.”

Rabbi Judah Mischel, a frequent guest teacher at Shalhevet who taught the boys’ sex ed. classes this year, recommended students struggling with questions of sexual identity speak to their parents, school counselor Rachel Hecht or a member of the Judaic Studies faculty.

Jenny thought school could do more.

“I would hope that Shalhevet teachers and administration continue to be sensitive to the issues that students address,” she said, “and to provide a welcoming community and family environment in which they can feel accepted being who they are regardless of who that is, and that it doesn’t pass judgment on them for that,” said Jenny.

Rabbi Steven Greenberg: Twice the power of love

The Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary of Yeshiva University has ordained thousands of rabbis since its founding in 1896. Rabbi Steven Greenberg of Boston is no exception, except for the fact that he is the first openly gay Orthodox rabbi in the world.

Rabbi Greenberg grew up in Columbus, Ohio. He went to Yeshiva University and Yeshivat Har Etzion in Gush Etzion, one of the most well respected in the world, headed until last week by HaRav Aharon Lichteinstein z”l. Rabbi Greenberg now works as a faculty member for the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America. He lives in Boston with his husband Steven Goldstein and their four-year-old daughter, Amalia.

It was at Yeshivat Har Etzion, also known as “Gush,” that Rabbi Greenberg suspected he might be different.

“When I was 20, I was at Gush and I recognized that I was strongly attracted to another student,” said Rabbi Greenberg. “I told the Rav that I am pulled to both men and women. He responded to me, ‘My dear one, you have twice the power of love. Use it carefully.’”

Rabbi Greenberg received smicha (ordination) in 1983. In 1999, he he openly admitted to being gay and came out in an interview in the Israeli newspaper Maariv.

“I was already out to family and friends,” Rabbi Greenberg told the Boiling Point in an interview at Starbucks in Los Angeles last fall. “Then you come out to close family members, than parents, then you come out publicly.

“I was already a rabbi. For me it meant taking responsibility for all the gay kids out there. I could no longer call myself a rabbi if I wasn’t a rabbi for them.”

Rabbi Greenberg’s smicha has not been revoked. Still, a significant portion of the Orthodox rabbinate is troubled by what he is doing and some have spoken out vehemently against him. A hundred Orthodox rabbis signed a scathing email letter to him when he first officiated at a gay commitment ceremony in 2011.

Some of the negativity is in reaction to his forays into the media. In 2001, Rabbi Greenberg appeared in a film called Trembling Before God, about the struggles Orthodox Jews experience growing up and concealing a secret.

Then, in 2004, Rabbi Greenberg wrote an award-winning book titled Wrestling with God & Men: Homosexuality in the Jewish Tradition, which won the Koret award which is an award for excellence in Jewish prose.

Rabbi Avi Shafran, spokesman for Agudath Israel of America, responded to the film.

“What Rabbi Greenberg apparently believes is that elements of the Jewish religious tradition are negotiable, that the Torah, like a Hollywood script, can be sent back for a rewrite,” said Rabbi Shafran in a reaction post titled, “Dissembling Before God – The Agudath Israel Response.” “That approach can be called many things, but ‘Orthodox’ is not among them.”

Other attacks have been up close and personal. Rabbi Greenberg described a time when a religious Jew confronted him in New York City.

“I had just come out two weeks prior,” Rabbi Greenberg said. “I was walking in New York and a man started screaming at me, ‘You public homo, you sicko-disgusting, go back to the bars and clubs where you belong.’

“I experienced these words not in me but flowing by me,” he said. “He was looking at some monster that didn’t exist. I didn’t need to be defensive or fearful or hurt or angry — I need to help him see better.”

He replied more forcefully than usual, he said.

“I responded, ‘I am afraid that I will be your worst nightmare. While I don’t go to clubs, I go to shul, a lot. I have lots of gay friends and we will push our baby carriages into your shul and we will not leave.”

There has been much progress in attitudes toward homosexuality in the intervening years. But Rabbi Greenberg said it can still be quite a struggle, and teens who think they may be gay should be prepared.

“There is no way all environments will be safe, so learn to be resilient,” Rabbi Greenberg said, “and what that means is that when people say homophobic remarks to you, they are speaking to monsters in their head. You are not the monstrous person.”

And he had this advice for students who might be gay at Shalhevet.

“The most important thing to know is that God loves you and the Jewish community is getting better,” said Rabbi Greenberg. “You will have a great life, relax, get through high school and things will be alright, don’t be too frightened by the future. I promise you that there will be Orthodox communities proud to have you as members.”

Benjamin Kenner • Jun 18, 2015 at 11:25 am

As a former shalhevet student and queer trans man this series of articles means a lot to me. Reconciling my identity and orientation with my faith is a long hard road and articles like this make it easier. I want to praise you for putting the voices of actual queer Jews in this article instead of just having straight rabbis talk about the issue. That goes a long way to helping people like me see that our voices and experiances have value.