No bribes, but Shalhevet students have an edge for college

Combination of advantages makes admission easier; some students feel disadvantaged because of programs to even playing field

June 12, 2019

No Shalhevet students were involved in the nationwide college admissions bribery scandal. But merely attending Shalhevet almost certainly grants them an advantage over students at most public schools.

“People have the assumption that college admissions is a meritocracy,” said Ms. Aviva Walls, Director of College Counseling and Dean of Academic Affairs. “It’s not. It never has been a meritocracy. There are all sorts of ways that try to rig the system to make it as fair as possible, but it’s an unfair system.”

Ms. Walls said that there was a vast difference between Shalhevet students’ and public school students’ experience applying to colleges.

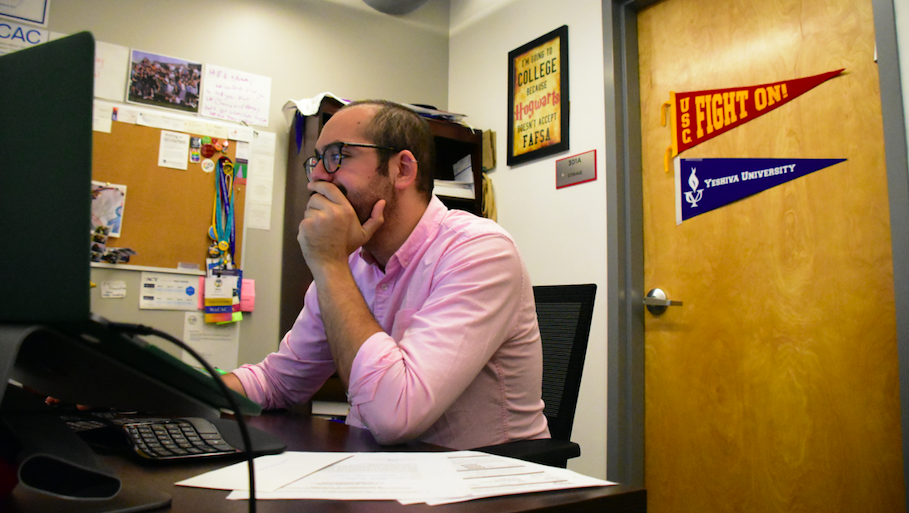

For a senior class numbering 64 students this year, Shalhevet has two college counselors, both of whom worked on the college side of admissions before. Ms. Walls was an admissions counselor at Barnard College and Senior Assistant Director at the NYU Office of Admissions, and Mr. Eli Shavalian worked as Assistant Director of Undergraduate Admission at USC.

That is luxurious by national standards. According to a study published by Education Week, the average public school college counselor is responsible for 470 students.The same study found that only a third of the nation’s high schools have any college counselor at all. About two-thirds of private schools do.

“Having a college counselor who can make a phone call to college admission offices is huge,” Ms. Walls said, as is having “two people who have been admission officers who can read applications with a critical eye.”

Also important is the counselor’s’ ability to bring admissions officers to Shalhevet to meet students and have a look around.

“We are in a position to say, ‘Who are our friends who we can bring to talk to our students?’” Ms. Walls said.

That means Shalhevet students can personally meet college admissions officers, who travel around the country to meet students and college counselors — only at certain schools out of about total 37,000 U.S. private and public secondary schools.

Pre-college events like essay workshops, grade-level college nights and case studies nights may exist at other schools, but without college admissions officials as speakers.

“Students who are in less resourced schools, even when their college counselor has the resources and the know-how to do that, they don’t get the same RSVPs,” Ms. Walls said.

These differences alone are enough to provide Shalhevet students with a substantial advantage in applying to colleges and universities of all types.

But Shalhevet students also have advantages in preparation for the SAT and ACT exams.

Not only do they receive a better education all along — because of things like smaller classes, and more parental involvement, advanced equipment and advanced course offerings on topics required for the test — but many receive outside tutoring for these tests.

In a poll conducted in October of 29 Shalhevet students who were preparing to take the SAT or ACT, 19 said that they had a tutor. Sixteen of 29 polled said that they spent at least $500 on study methods.

Joshua Lord, who tutors students at Shalhevet and elsewhere for standardized tests, said those he tutors and who keep up with studying can see a 160- to 200-point gain on the SAT, which is graded out of 1600 total points, and three to six points on the ACT, which is graded out of a total 36.

Mr. Lord said that private school students tend to come into his tutoring at an advantage, which he believes is due to the attention paid to students at those schools.

“There is more attention to the particular student at private schools,” said Lord. “Private schools tend to be really good at using their resources to have smaller class sizes” and more interaction from the college counseling department with students.

Responding to this, colleges that see their education as a way for the less advantaged to move up are trying to even the playing field somewhat, even if it will never be exactly possible. Ms. Walls supports their efforts.

“I don’t think we should all be born on third and think that we hit a triple,” said Ms. Walls. “I think that we should recognize that we’re in a fortunate position. And that is literally the very least we could do.”

Measures have been taken by both the College Board, which runs the SAT, and some colleges, including UCLA, to account for the disadvantages faced by students who are less privileged and bring economic and social diversity to their campuses.

For example, since 2017, the College Board, the company that runs the SAT, has been testing an “Environmental Context Dashboard” for SAT takers, supplying the score to 50 colleges.

This feature, which has been referred to as an “adversity score” measures disadvantages found in a student’s school and neighborhood. They include college attendance, median family income, local crime rate and more. The student is given a rating between one and 100.

Last month, the College Board announced it would cover all schools beginning in 2020.

The dashboard “allows colleges to incorporate context into their admissions process in a data-driven, consistent way,” the College Board’s website says.

Another example is being used by UCLA. To compensate for students having different backgrounds, Ms. Walls says that instead of judging applicants against all other applicants, UCLA Admissions has begun to judge them relative to students from their own high school.

That would mean that a student from Shalhevet who had a high GPA would be in a lower percentile in their school than a student who had the same GPA who came from a school with a lower average GPA.

“It really gives a numerical context for the student,” said Ms. Walls. “The student who’s coming from Shalhevet is going to have a very different reality of what those percentiles look like than a student coming from the Central Valley, where there’s very different-college going culture, or from South LA or from East LA.”

In a 2017 study conducted by Opportunity Insights, of all elite colleges ranked, UCLA was the highest in its “overall mobility index” which measures “the likelihood that a student at UCLA moved up two or more income quintiles” after receiving a UCLA education.

But in spite of their advantages, some Shalhevet students believe the reverse is true: that being more affluent and not belonging to a racial minority puts them at a disadvantage when applying to college.

According to a Boiling Point poll taken May 28 at lunch, a third of Shalhevet students expect extra hurdles when they apply to college, compared to students who are racial minorities and-or come from less privileged backgrounds.

Of 75 students who responded, 33.8 percent responded to the question of “Do you believe your race or ethnicity put you at a disadvantage in being admitted to colleges?” with “yes.” They were also asked about their own race; all but one who answered “yes” were white.

Junior Joseph Klores said he believes a minority student who had worse grades than his might be admitted over him because of his or her race.

“If I have a similar resume to someone who’s black, and mine’s a little better but they’re black, they’ll probably accept the black person because they’re black even though I have close to a whole better resume,” said Joseph.

Junior Jacob Benezra, who is the only African-American student at Shalhevet, does not see a problem with accepting a minority student who has relatively similar or slightly lower grades compared to a white student.

“If it’s just this kid who’s just straight D’s but because he’s black, we’re accepting him into college, then I don’t think that’s right,” said Jacob. “But if we’re giving them the same opportunity for them to shine and really prove themselves, that they can be a part of this situation, then I think we can set the bar maybe a little lower, because of their background — then I think that’s okay because diversity is important.”

Ms. Walls said that there was a vast advantage for Shalhevet students applying to colleges.

She agreed that colleges seek students from diverse backgrounds, and since the majority of applicants do not come from those backgrounds, they they keep their eyes open for strong disadvantaged or minority students.

But she said that “doesn’t erase all of the advantages that our students have.”

College applications – including the Common App, used by over 800 colleges — ask for students to list their race on their applications. The Oxford English Dictionary defines race as “Each of the major divisions of humankind, having distinct physical characteristic.”

While the degree to which students’ race affects admissions is a matter of contention, most Americans believe that it should not have any influence at all, as shown in a recent Pew Research study finding that 73 percent of Americans believe that colleges “should not consider race or ethnicity when making decisions about student admissions.”

Even race and ethnicity sometimes work to Shalhevet students’ advantage, however. Students whose parents come from Latin America, South Africa or Morocco have geographic backgrounds that distinguish them from European or Middle Eastern-origin whites, and some of them say so on the Common App.

The application asks separately whether a student is Hispanic or Latino, which would be an ethnicity — defined by The Oxford dictionary as “The fact or state of belonging to a social group that has a common national or cultural tradition.”

Sophomore Mimi Czuker, who is white, said that while she sees a need for addressing disadvantages, the Environmental Context Dashboard is not the right way to go about it.

“I think the main reason that it bothers me is because [disadvantage] is not the kind of thing that can be measured,” said Mimi. “I think there’s a lot of different factors that go into it…. Maybe there are even more disadvantaged people that won’t be measured either. What if, let’s say, their parents have money but they’re not willing to spend it on that?”

Sophomore Alessandra Judaken, who is Latina, agreed.

“Although it is to my advantage, I would have to say I am completely against this,” said Alessandra. “People should be getting accepted to college for what college is for — academics and education, not by the color of their skin.”

Alessandra disagreed with the Environmental Context Dashboard plan.

“Both my parents are immigrants,” Alessandra said, “and they worked day and night, constantly working, three jobs at one point and four jobs at one point, not coming home at night so I don’t have to worry about money, so I don’t have to worry about the college process and tutors and everything like that.

“Life isn’t fair and everyone should be treated and accepted into colleges equally, and based on their standardized test scores, grades, what they have accomplished or are involved in, and their application. That’s it.”

Jacob agreed with Alessandra that he has an advantage because of his race.

“Baruch Hashem I’m with you guys,” said Jacob referring to white students at Shalhevet. “I am at an advantage just because I have the resources to get into good colleges, plus I am a minority so I have a combination of both.”

Ms. Walls said that when it comes to students choosing how to describe their ethnicity, it is for the most part a personal choice.

“Your identity has to start with yourself,” said Ms. Walls. “We’ve had students who have identified as Latino or Asian American even African-American before. If that’s a huge part of your identity that is a piece of who you are I think you should express that on your application.”

Jacob Benezra said that ideally race would not be a factor, but that the correlation between racial minorities and more socioeconomic and educational disadvantages — the poverty rate for white Americans was 8 percent in 2017, while for black and Hispanic Americans, it was 20 and 16 percent, respectively — necessitates action by colleges.

“We can all agree at the end of the day, if we had a perfect world, it should never come to race,” said Jacob. “But I think the reason why it comes to race is because of how the system is already set up. Black people, Latino people, they’re living in terrible conditions and that goes all the way back when America first started…

“Right now race plays a role because, I wouldn’t say we’re trying to fix the past, but we’re trying to give opportunities to those people.”