REALITY CHECK: So-called ‘finsta’ accounts bring a different view of teen life to Instagram

More and more students are using second Instagram accounts, shared only with close friends, to escape from having to look picture-perfect in cyber-public.

January 9, 2017

On Oct. 27, senior Layla Galeck posted a photo of herself to Instagram from her vacation to Israel during Sukkot break. It was a smiley photo of her and her brother on a beach in Tel Aviv, surrounded by clear blue water and an even clearer and bluer sky.

She captioned the photo with an ocean wave emoji. It received 212 likes.

From the same trip, she also posted a dimly lit, unflattering selfie to her “finsta” — her “fake Insta” — a second, separate Instagram account she shares only with her closest friends. She captioned this photo with the truth about her time in Israel that October.

“Currently sick, huge headache and sad…TBH tho u all know I’m gonna make sure to make it looks like I’m having the best time over Snapchat and other social media apps bc that’s what social media is all about!!! Woohoooo let’s go #FakeItTilYouMakeIt.” Graphic from Instagram.com

Graphic from Instagram.com

The photo received 10 likes.

According to a poll of 96 Shalhevet students taken last month, 43 students (45 percent) have finsta accounts. They use them as an intimate social media platform, something to share just with their closest friends.

A portmanteau of the words “fake” and “Instagram,” finsta is a second account created on the Instagram app, formed in addition to what teenagers call their “real” or “main” Instagram accounts. At Shalhevet and elsewhere, they are fast becoming a popular supplement to mainstream social media platforms like Facebook.

The accounts are ostensibly private, so kids post things there that they would never dream of posting to their main Instagram account or Facebook — including ugly, embarrassing photos, very personal information, and photos or videos of them smoking, drinking or partying, or inappropriately dressed. Some of these postings are meant as emotional or artistic statements, while others are just flaunting convention.

These posts deliberately contrast with the quality selfies, artsy landscapes, and generally flattering photos that are typically found on main Instagram accounts and or Facebook.

“It’s like that saying, ‘A drunk person’s actions are a sober person’s thoughts’ — you know, like what they wish they could say,” said junior Maya Schechter. “This is kinda of like that.

“This is all the stuff I want to post but because it’s not acceptable or it’s not like what everyone else is posting, I don’t post it to my main. But I can put it on my finsta.”

Students who have finstas say they feel relieved after posting, say, a long rant or a personal post. Junior Maia Zelkha, who often posts to her finsta multiple times a day, described the trend as “an online photo-journal.”

“Finstas are people’s journals that they’re showing to people, because it’s not just partying and drugs,” said Maia. “People actually make very personal posts in their finstas…a lot of how they’re feeling. It’s allowing yourself to be vulnerable.”

This online environment of controlled vulnerability creates a certain feeling of unbottling emotions and struggles, students said — perhaps not unlike the feeling people get when speaking to a therapist.

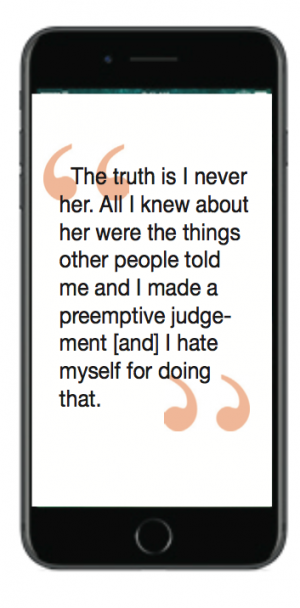

A senior girl who did not want to reveal her name posted in October about someone in the community who had died last year in a car accident.

“The truth is I never knew [her]…,” said the post, which got 11 likes. “All I knew about her were the things other people told me and I made a preemptive judgment on the person she was before I even knew her and I hate myself for doing that.

“I hate that it’s so common for this situation to happen nowadays,” the post continued. “It hit me so hard when she passed away because I realized what I had done wrong and I would never have the chance to get to know the wonderful characteristics that all of her friends and family miss so much. I wish I could apologize and learn who she was really. In her memory, I promise to work on myself. To never judge a person before I truly understand who they are. I wish I knew that before.”

On main, or typical, Instagram accounts, teens compete with their photos for quality and a good appearance. On finstas, they may compete to see who can have the longest rant, the most embarrassing photo, the wildest photo from a party, or even the best semi-nude.

Half of Shalhevet students who have finstas said they’d posted something inappropriate that they would not post to their main account. However, 82 percent reported seeing something they considered inappropriate on someone else’s finsta (not necessarily belonging to someone at Shalhevet).

Videos and pictures of students smoking and drinking or holding an alcoholic beverage were among the most common types of inappropriate posts students said they had seen. Even more common, according to an optional comment section on the poll, were pictures that were mostly or partially unclothed.

One anonymous girl who posts such images said it is because of the ostensible privacy a finsta grants.

“Family and friends and random people follow my main account, which stops me from posting pictures of me that look good but aren’t so ‘appropriate,’” she wrote.

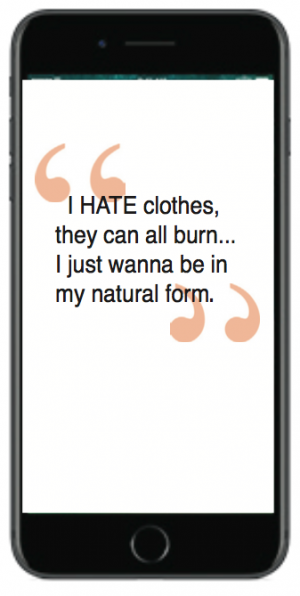

A girl who did not want her name used in this article posted a photo in which she was nude, but because she was sitting down with her knees bent and pressed against her chest, her shoulders, legs and long hair dominated the photo, which actually revealed little else.

She captioned the image: “I HATE clothes they can all burn, underwire wedgies and armpit sweat, God I hate it, I just wanna be in my natural form.”

“If you ever take a picture of yourself that you really like, and nothing is completely showing, it’s nice to post a picture like that and get the likes and comments and feel good about yourself, you know?” she said.

Maia Zelkha said the posts other people make to their finstas are almost predictable on Sunday mornings, after parties the night before. She said it can even get competitive.

“It’s repetitive sometimes,” said Maia, who follows finstas of friends at several different schools. “It’s always posts about how they’re so hung over from last night, or posts that say ‘Oh my God what happened last night?’ and it’s every Sunday morning. People posting snapchats to their finstas of them partying with vodka. Your finsta is almost a way to outdo people in how experienced you are.”

In the poll, most students said they had started their finstas because their friends had one, and or it seemed fun and they wanted a place to post rants, funny photos, or personal information that they couldn’t post to Facebook or their main Instagram account.

But once students made their finstas, they entered a social media game with entirely different rules than the ones for mainstream social media accounts like Facebook or real Instagrams.

For one thing, finstas are always on Instagram’s “private” setting, meaning if you want to see someone’s finsta, he or she must accept your follow request. This game of follow requests poses a dilemma to teens. Students want their finsta followers to be mostly close friends so they can post what they want, but students might feel awkward declining someone’s follow request.

Rejecting someone’s “follow” request on your finsta is essentially the social media version of telling them “You can’t sit with us” at lunch.

According to the poll, finsta accounts have between 30 to 60 followers on average, whereas main Instagram accounts usually have between 300 and 400.

“The exclusiveness is a fundamental part of the finsta, but I feel like it’s more damaging than it makes anyone feel good,” Maya Schechter said. “It’s become very elitist, exclusive, cliquey…it turns this fun thing into this exclusive club: you can’t follow my account, you are not in this, you can’t be a part of this, you don’t know me, we’re not friends. That’s what it says when it says ‘pending’ a month later, and it really hurts.”

Maya said she now accepts almost everyone who requests her finsta, which currently has a follower count of 150. But accepting everyone comes at a cost. Maya said that since her follower count went up, she has deleted some of her more personal or embarrassing posts, and posts less to her finsta account.

More recently, this problem has resulted in a new solution: a third Instagram acount — a “private finsta,” “super private” or “super finsta,” as they are being called by the teenagers creating them.

Like finstas in general, this solution isn’t confined to Shalhevet.

“As more people made finstas it kind of became a social convention where you just followed everyone’s finsta regardless of whether or not you were friends,” said Ariel Frig-Levinson, a junior at Milken Community High School. “But my finsta was meant for me to post private stuff…So I ended up making a super private, which I only let 20 people follow, and it’s where I actually talk about my life.

“Honestly, if I’m friends with you, you’ll get accepted to my finsta, but my private finsta is for my closest best friends,” said Ariel.

With his private finsta, he can reach all of his closest friends at once, he said, even if they’re in different social groups from one another.

Names of finsta and private finsta may be puns of real account names, or references to a real name or a personal trait. One junior boy who likes buying inexpensive clothing named his finsta “costco.couture.”

Of the 53 Shalhevet students who do not have a finsta, four had never heard the term before, 80 percent did not want one, some had other reasons for not having a finsta account and three students had had one and deleted it.

“It created drama when you didn’t accept people,” a freshman girl said. “It’s unnecessary to pretend to be someone else on your main.”

Most students who did not want one wrote that they felt it was either unnecessary or too time-consuming considering all the other social media accounts teenagers have to be on top of.

Of the students who have a finsta, 87 percent were female, and most of the students who did not have a finsta were male, the poll reported.

Boys made up 55 percent of the people who did not have a finsta. Most of them said they did not have one because it’s unnecessary when they already have a main account.

Junior Daniel Lorell said he originally made a finsta to satirize traditional finstas, but lost interest in the idea. Since then, he only uses his main account.

“I see no need — I would post anything I wanted to post on my main account,” Daniel said, echoing the thoughts of the majority of boys at Shalhevet who do not have finstas.

Girls with finstas think boys are less likely to have them because there is less pressure on guys to look perfect on their main account. But it would seem that for many teens, finsta fills a need — a need to rebel against all the norms of social media, and to fight against the pressure they feel to look perfect all the time.

Teenagers have probably always looked for ways to express their truest fears, feelings and secrets, their most vulnerable points and unflattering moments — ironically, making “fake Instagram” posts more real, and “real Instagram” posts essentially fake.

“My finsta is really an insight into my real life, on my real Instagram and Facebook I’m posting all these photos where I’m having the best time ever, and sometimes I’m not,” said senior Layla Galeck. “I let my close friends follow my finsta, and show I’m having a terrible time right now, but I’ll make it funny and post an ugly photo with a rant in the caption. It’s real.”

“We are all are trying to portray this person that’s really not us,” Layla continued. “We’re all trying to make our lives look perfect and flawless, and none of our lives are actually like that. It’s just to impress people.”

This story won two prizes — Second Place for In-Depth News / Feature story and Third Place for Cultural Features — in the 2017 Gold Circle Awards of the Columbia Scholastic Press Association.

Not as private as you think: Finsta posts are permanent, shareable and retrievable, like anything on the Internet

Because finstas are always set by the user to be on finsta’s private setting, they are also sometimes referred to as “private accounts,” or “privates.” However, these accounts are no more private than a main Instagram account or a public Facebook.

Finsta posts can be shown to anyone, and even screenshotted and passed around through text messages. In a poll taken last month of 97 Shalhevet students, one 12th-grade boy said he had not made a finsta because he was worried his followers would show other people his posts. He is right to be concerned.

“When people are posting things online, you have to approach it as always public and permanent,” said Dr. Eli Shapiro, an educational consultant who has been speaking for a decade on a broad range of topics from cyberbullying, to substance abuse to internet safety.

Just because a finsta account cannot be accessed easily does not mean it cannot be accessed at all. Dr. Shapiro says most companies do a cursory background check of potential employees, but more corporate jobs may hire research companies on retainer. By connecting your e-mail account to the rest of the worldwide web, these private companies can find a lot more than just what is on your public Facebook.

Finstas can also be subpoenaed by the police, if the content of the post could be perceived as illicit. What could be cause for a legal request cannot be exactly defined, because those things are on a case by case basis.

“If it’s a 16-year-old holding a red cup at a party and it looks like it could be alcohol, this is a tricky situation,” wrote cyber safety expert Lori Getz, who spoke at school last year on the topic of sexual consent.

“It’s very difficult to prove that what was inside that cup is actually alcohol,” she said. But “if the 16-year-old is holding a bottle of beer that is clearly labeled, then there may be an opportunity for investigation.”

According to Instagram’s privacy policy — which you click “agree” to whenever you start an account — the company “may access, preserve and share your information in response to a legal request (like a search warrant, court order or subpoena) if we have a good faith belief that the law requires us to do so.”

The explanation appears in a section of the policy titled “Responding to legal requests and preventing harm.”

Posts are forever. Even if someone deletes a post of drinking underage, doing drugs, or something else that is in direct violation of the law, Instagram and legal authorities can still see it. In the privacy policy, Instagram also writes that your information “…may be stored and processed in the United States or any other country in which Instagram, its Affiliates or Service Providers maintain facilities.”

“By registering for and using the Service you consent to the transfer of information to the U.S. or to any other country in which Instagram, its Affiliates or Service Providers maintain facilities and the use and disclosure of information about you,” the policy states.

Instagram also clearly warns they keeps your information, even following “termination or deactivation of your account.”

“Instagram, its Affiliates, or its Service Providers may retain information (including your profile information) and User Content for a commercially reasonable time for backup, archival, and/or audit purposes,” the contract says in a portion of the Privacy Policy called “Your Choices About Your Information.”

Security and legality aside, students should think before they post.

“It’s not just about law enforcement and legality, it’s about your digital footprint,” Dr. Shapiro said. “What are you putting out there and how is it shaping others’ perception of you?

The reality is people save things if they can, he said. Dr. Shapiro put finstas in context of the recent presidential election, in which a decade-old video of Trump making sexual comments resurfaced, as did private e-mails of Hillary Clinton, obtained by Wikileaks apparently received from Russian hackers.

“Comments you made 10 to 15 years ago can come back to haunt you,” Dr. Shapiro warned.

This illusion of privacy, combined with what Dr. Shapiro said is called “online disinhibition,” in which people are much more impulsive online, means they should start being more thoughtful and deliberative then they post.

“If you want to use a finsta in order to make your circle a little bit smaller that’s fine,” Ms. Getz wrote in an email to the Boiling Point. “Just remember that you are trusting these people to now control the information you have provided.”

Because of this, she does not consider finsta accounts to be private.

“If we define the word private as control, meaning that you can control who sees what, who knows what, how much they see and how much they know, then we have to ask ourselves do we control the information once we’ve posted it? The answer is simply no.”

This is true of all social media, both experts said.

“There’s a whole trend of anonymous social media, where there’s the perception of anonymity,” said Dr. Shapiro.

“In some cases it’s more real than in other cases, but even in completely anonymous spaces like Yik Yak, or Whisper the actual user can be traced by police or other legal authorities through the IP Address, there is nothing truly private.”