Illustration by Ariella Sassover and Mel Keefer

FIRST IN A SERIES: The Positives of Partying

While partying may be dangerous when mixed with alcohol and drugs, a Boiling Point survey shows parties have benefits. too. Can high school students benefit from the good without joining in the bad?

May 10, 2016

Partying has a bad rap. Google “partying statistics” and you will find a plethora of sobering statistics and stories about underage binge-drinking and drug abuse.

What you won’t find is data about friendships, relationships, grades’ bonding, and positive social experiences that happen outside of school, co-curriculars or social media and which form, develop and flower during parties.

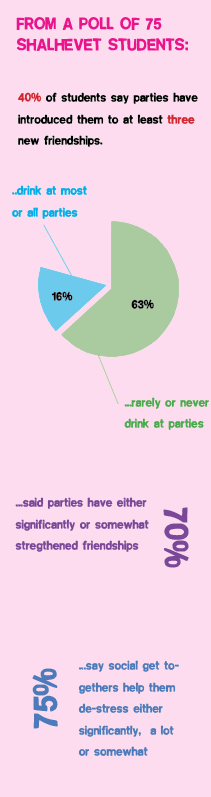

According to a poll of 75 students taken March 22 at lunch, 40 percent of students say parties have led to at least three new friendships. Most of these friendships involve someone from outside of Shalhevet, thus creating both meaningful social interaction and an escape from the “Shalhevet bubble.”

“As far as Jewish schools go, the Jewish community is very restrictive on how you can meet people so to meet people from other schools, parties definitely help with that,” said sophomore Mendy Mentz.

“There are so many things that have been said about parties that make it seem negative, when really it must have some positivity because it’s been so engraved in teenage culture for a lot of years.”

Whatever its pluses, parties also usually have alcohol, which may be the source of their bad reputation. The majority of students polled – 63 percent – say they rarely or never drink at parties, but 16 percent said they drink at most or every party.

Subtracting freshman from the equation lowers the non-drinking group to just 53 percent, and 18.3 percent of non-freshman polled drink at most or every party. Everyone else answered “sometimes.”

In fact, asking Shalhevet students about parties nearly always elicits an answer that includes the word “alcohol.”

But parties are also, they say, the easiest way to meet new kids.

“There are ways to get out of the bubble without alcohol and parties but it’s much harder,” said an anonymous sophomore. “You’re not just going to go up to someone in a pizza place and be like, ‘Hey, what’s up, wanna be friends?’”

When inappropriate substances are on-hand, they are apparently there partly as a symbol, not for use. If there is alcohol at a social gathering, partygoers generally feel more relaxed even without consuming it, students said.

At least two students said they and their friends sometimes “pretend to drink, just to experience the placebo effect of feeling loose and calm.’’

Senior Boaz Willis said the presence of alcohol implies an atmosphere of relaxation and intimacy among the guests, whether at a party or at a kickback. Like a party, a kickback — a small social gathering of close friends — is typically associated with drinking.

“The culture of a kickback implies that there’s going to be drugs or alcohol there,” Boaz said. “There’s obviously a different vibe to doing things like bowling recreationally than going to someone’s house and hanging out with a bunch of people,” he continued. “I don’t think that people would be so interested in hanging out with 20 kids from their grade at somebody’s house if there wasn’t that aspect of recreational drug and alcohol use.”

On its own, socializing holds an important place in the lives of teenagers, psychologically and culturally, experts say.

Jennifer Silvers, Assistant Professor of Psychology at UCLA, said it is normal to have an increased interest in being around your friends when you’re a teenager. In fact, not having such an interest may be abnormal.

“If people aren’t interested in their peers, meeting someone new, or taking any risks at all, sometimes that’s a sign of depression or it might mean that something’s not quite right developmentally,” Professor Silvers said.

The Boiling Point poll also found that parties and kickbacks tighten existing friendships. Seventy percent of students noted that parties either significantly or somewhat bond friendships and relationships they already have.

SAS Psychology teacher Ms. Tove Sunshine said research shows one of the most important influences in growing up, especially in the teenage years, is interaction with peers.

This turns out to be especially important for teenagers who plan on living independently or going to college. According to Prof. Silvers, a study conducted by the University of Minnesota found that children suffer less during a painful event when a parent is nearby, but that once people enter adolescence, friends take that place of a parent and can be just as effective in decreasing distress.

For that to work in times of pain, friendships need to be close.

”

Seventy-five percent of students polled said social get togethers help them destress either significantly, a lot, or somewhat.

“Students are in school for five days a week and most people like to de-stress in some form, and their remedy may be partying,” said Asher Dauer.

Learning actual life skills is another apparent benefit of parties and kickbacks. Fifty-two percent of students polled wrote that parties contribute either significantly, a lot, or somewhat to gaining real life competence.

Many polled and interviewed by the Boiling Point said parties made them better at meeting new people, being resourceful when it comes to late night transportation, and confidence.

In response to a question prompted in the survey, anonymous students said going to large social gatherings taught them responsibility, self-control, knowing their limits, and to be more aware of their surroundings. In the face of so much peer pressure and the accompanying risk of forced activity, it may actually be the perfect time for teenagers to learn to say “no.”

“There’s a lot of times where people wanna ‘get with’ you, but you learn to know when to say no and when things are getting too much, you learn to remove yourself,” said one sophomore girl.

According to Ms. Sunshine, that particular ability can actually prevent the major psychological and social phenomenon that causes party mistakes: group-think.

“The dynamic of group-think is a close group with tight connections with a strong commitment to the identity and closeness of the group,” Ms. Sunshine said, “and that can overcome individual judgment in terms of decisions where people don’t want to speak up and be critical because it damages that group thinking.”

The way to avoid that is to recognize in advance the significance of decisions that you’ll be making and to urge others to speak up, she said. Ms. Sunshine advised creating an atmosphere that encourages critical response and not making people feel like they’re damaging the group’s sense of cohesion by thinking independently.

This is a bit harder when the situation is social, she said, since then it is natural to “want to foster social harmony.” Generally, students should have a conversation to create a group consensus of their goals — for example respect for individuals, not putting pressure on people, and a group value of feeling safe to express different opinions.

Ms. Sunshine said that although the conversation is the hard part, informally and continually discussing group norms instead of valuing harmony above all is ideal. Partying with these goals in mind should make it easier to harbor and accept individual feelings and choices – which in turn should make it easier for people who want to stay safe to do so.

Prof. Silvers said group-think and adhering to peer influence generally declines quite a bit even over the course of high school. People are most sensitive to peer influence in middle school, ages 10-14, she said.

But senior Daniel Soroudi expects college parties to be worse than high school parties. He said his brother, alumnus David Soroudi ‘10, told him parties at USC are much worse than the ones in the Shalhevet community.

That’s made Daniel think going to parties now is a chance to learn to deal with, and break, “group think.”

“Just by going to a party or kickback that isn’t as intense as college parties, you’re able to almost prepare yourself for something bigger,” Daniel said.

Prof. Silvers agreed, saying research shows it is better to learn skills incrementally – that is, a little at a time.

“Look at a kid who’s learning how to walk,” she offered as an example. “You want them to first try it in short spurts with their parents nearby. The second time you give them a little bit of space to walk on their own. You don’t want their first attempt to be walking three miles.”

Some research has shown early exposure to alcohol may lead to substance abuse as an adult. A study from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism states that those who start drinking before the age of 15 are four times more likely to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence.

But Prof. Silvers countered that even when professionals know that someone tried alcohol at 14 and has now problems with drinking, it’s not clear whether it’s the cause. Perhaps it’s because they tried it at a young age, but maybe they’re more risky and impulsive by nature, and that’s what led them to both try alcohol younger and have problems with it later in life. In other words, early exposure is not the only variable in adult life substance abuse.

Whatever the answer to that question, parties are here to stay. That means students need to find a way to avoid the bad so they can make the most of the good — socializing, preparation for the adult world, bonding, and de-stressing.

If they can avoid the pitfalls, parties may even help them live longer. Studies show socializing and having close friend groups decrease stress, thus increasing longevity. According to 148 studies gathered together by researchers at Brigham Young University, strong social relationships meant a 50 percent increase in long-range survival, on average, across a range of diseases ranging from neurological problems and kidney ailments to heart disease and cancer.