TEACHER TALK: Changing trajectories

Mr. Reusch, who lost some of his earlier students to gang violence, tells Shalhevet students to be "aware of their privilege" and strive to make a difference.

November 21, 2015

With 600 kids in his high school graduating class and teachers who did not know his name, Will Reusch found his school experience in Bethlehem, Penn., to be discouraging. He planned to be a police officer.

“I did not make the connection between school and my lifelong happiness,” said Mr. Reusch, who teaches American History and Government and Economics at Shalhevet.

His parents had emphasized the importance of working in a field that benefits the greater community, as well as the value of diversity. So he enrolled in Penn State University expecting to study law enforcement. But on his first day of college, his professor spoke about the police purely in terms of the power they wielded — not the justice they were charged to uphold — prompting Mr. Reusch to change his major.

He began to consider whether he might make a bigger difference as a teacher, offering students a more meaningful experience than he had in high school.

“I figured I would get to the criminals before rather than after,” Mr. Reusch said in a Boiling Point interview. “I want to get to people headed down a criminal or destructive path, and change their trajectory.”

Since then, Mr. Reusch has worked toward this ideal at an eclectic group of schools, including a predominately African-American school, an all-Hispanic school and now the Modern Orthodox Shalhevet. Surrounded by a diverse group of friends and married to Sheila, who was born in the Philippines, Mr. Reusch seeks difference. (They have a son, William Reusch IV, nicknamed Beau to prevent family confusion).

In his previous teaching positions, Mr. Reusch faced the difficulty of classroom management and students who entered his classroom lacking the basics. Some, for example, were not familiar with Abraham Lincoln.

They also resided in poor and unsafe neighborhoods. Six or seven were shot — two of them died — while he was their teacher, due to gang membership, robbery and simple bad luck, he said.

Mr. Reusch visited one of these students, who was in a coma after being shot in the head, at the hospital.

He did not, however, attend their funerals.

“I felt awkward going to a funeral — I wasn’t close to the family,” he said. “I felt like I was trying to get this experience. It was a self-righteous feeling and I didn’t feel comfortable with it.”

The overarching challenge of his previous jobs, he said, was “getting kids to understand that school is going to help them and is the easiest path to happiness and success.”

At Shalhevet, he has encountered new and different challenges. Mr. Reusch says that because of their solid educational foundation, the students require a lot of content, pushing him to stay ahead of the curve.

Here, he said, privilege itself is a challenge — a challenge to make the most of it and make a difference themselves.

“It is important to be aware of your privilege,” Mr. Reusch said. “Understanding the other side is really important. I would never want students here to be anti-Zionist, but I think that the idea of challenging beliefs that you’ve been told from your first days is an important part of growing up, and I think that is a tough thing.”

He was somewhat surprised to find that affluence carries pressures of its own.

“You are in this situation where you feel like you have all these opportunities,” Mr. Reusch said. “You think that that would be less pressure, but often times it is more.”

Mr. Reusch advises students not to limit themselves or focus solely on what college they want to go to.

“Kids are so concerned with the end game,” he said, “but if you are shooting for the goal, you miss the whole journey.”

And recalling the lesson that he learned from his parents about helping others, he said the journey should be worthy of students’ advantages — pressure or not.

“I think that you have almost unlimited opportunity, and I think that it is such a gift,” said Mr. Reusch. “I would hate to see it squandered.”

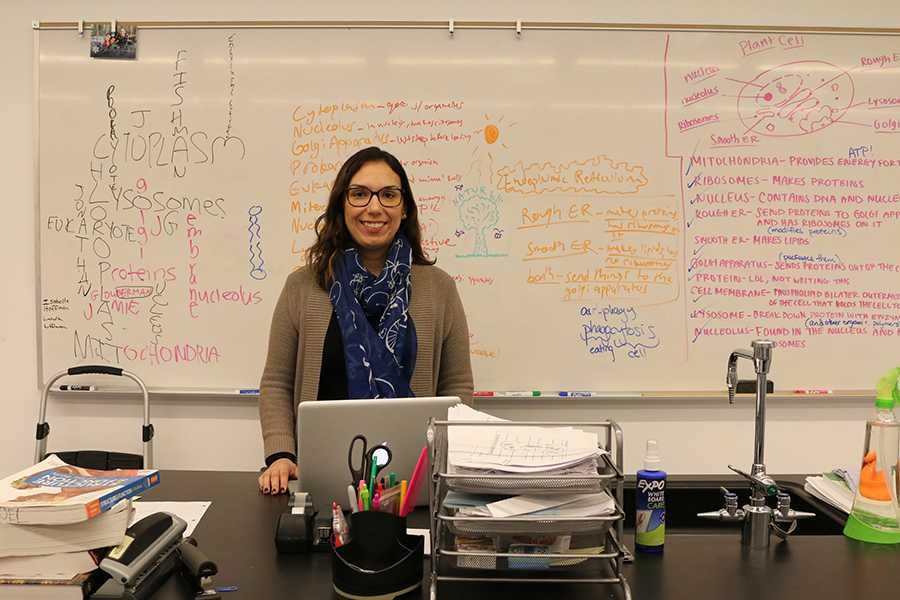

TEACHER TALES: A path to science and a new home

RESEARCH: Biology teacher Dr. Melissa Noel discovered one way that fetal alcohol syndrome leads to neuronal death and brain problems.

Determined to inhibit a serious symptom of fetal alcohol syndrome, Melissa Noel injects newborn mice with high doses of alcohol. Of these mice, only some contain tPA, a gene typically known for breaking down blood clots.

She then nervously tests the mice’s learning and memory abilities, anticipating whether her discovery of a new function of tPA, one that could save numerous children’s lives, will be confirmed.

The year is 2009, and she is at the David Rockefeller Graduate Program, a program in New York City that trains scientists and that has produced the largest concentration of Nobel Prize winners in the world.

This is where Dr. Noel obtained her Ph.D. in neurobiology. She currently teaches biology and physiology at Shalhevet High School.

Her results ultimately validated her hypothesis that tPA triggers neuronal death, indicating that the mice exposed to tPA developed cognitive impairments from alcohol, while mice who lacked tPA were not affected.

That discovery moved scientists a step closer to manufacturing drugs that target tPA and stop the progression of neuronal death in fetuses in the future. Dr. Noel was able to publish her research in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

But more than wanting to cure fetal alcohol syndrome, Dr. Noel’s upbringing was the ultimate motivating factor in her decision to move to New York in pursuit of a career in science. Growing up in Puerto Rico, her mother was a guidance counselor at the University of Puerto Rico and her father was an accountant at the same university. This gave him the opportunity to work simultaneously on a master’s degree in English literature, a pursuit he was very passionate about.

Her parents both grew up in poor families and were the first of their families to go to college. Her father, concerned about supporting his children financially, pursued accounting despite an aversion to it.

“He wanted to make my sister and me very aware that we could choose what we wanted to be,” Dr. Noel said in an interview.

Because of where they worked, Dr. Noel’s family was an impactful, and sometimes unavoidable, part of her life.

“I felt like I couldn’t escape my family,” Dr. Noel said. “I’d be walking with my friends in college and I’d see my mom walking, and I’m just like —‘I want some freedom.’”

Yearning for independence, she decided to apply for graduate programs in America.While she was at Rockefeller, Dr. Noel found herself enjoying the tutoring she did to supplement her scholarship. After getting her Ph.D., she felt unsure about pursuing a career doing research, and decided that teaching was more compatible with her personality.

“There’s something vibrant, youthful and fun about working with students,” she said. “We can have real conversations but you have a sense of humor that’s hard to find in adults.”

Dr. Noel advises current high schoolers to take the same risks she has.

“This is your time to discover what you’re about, so expose yourself to as many new opportunities as possible,” she said, “even if they make you feel uncomfortable. You need to be honest to yourself and honest to what it is that you enjoy doing and that’s what you need to pursue.”

And though her family still lives in Puerto Rico, Dr, Noel does not plan on returning. She said she stays informed about fetal alcohol syndrome, but that so far her research has not led to a cure.

Dr. Noel explained that since it’s a syndrome, there are many ways a baby can be affected, and it’s more realistic for science to strive towards treatment or prevention.