CHEATOLOGY: More than twice as many students say they cheat on Schoology as on paper

In BP Poll, more than twice as many Shalhevet students said they had cheated on Schoology tests as on paper exams. Administration has no plan to ban the tests, saying the problem is moral, not technological.

May 13, 2015

More than two years into Shalhevet’s use of Schoology– the online resource for teachers and students that has become the backbone of communication at the school– it turns out that the much-loved website facilitates something it was never intended to support: cheating.

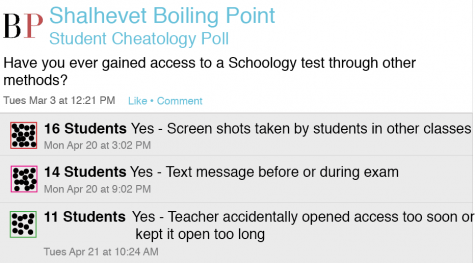

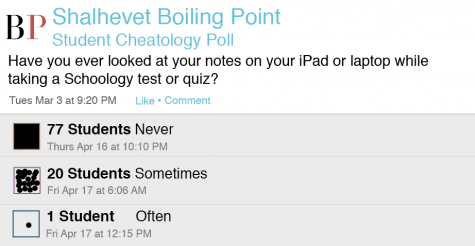

In a Boiling Point survey of 97 students conducted March 3, more than twice as many students reported cheating on Schoology as on paper tests, mainly through the illicit use of screenshots from exams given a previous period or day.

Exactly 50 percent of students (49 out of 98), said they had cheated on a Schoology assessment, compared to 20 percent (20 out of 98) who said they’d cheated on paper tests. Six said they had cheated both ways. Forty-three percent of students said they had not cheated at all.

In addition to the use of screenshots, students said they cheated by searching for answers on the internet, switching screens to look at their notes, or live-messaging classmates during the exam it-self.

Teachers who stand at the front of the room watching students for wandering eyes are unable to see what’s on iPad screens. But if they stand at the back to watch the screens, they can’t see students’ eyes to prevent their viewing neighbors’ answers.

“The teachers usually stands in the front of the class, which makes it easy for us to switch between screens without their knowledge,” said a freshman boy, like everyone else willing to discuss cheating, would only do so anonymously.

Specifics of cheating techniques were plentiful in the poll, taken anonymously on paper questionnaires distributed at Town Hall, which gave space at the bottom for cheating techniques. In the weeks afterward, the Boiling Point interviewed students to learn details.

One junior said when he logs onto Schoology on his iPad to take a test, he leaves his notes open on another screen, then just clicks the home button twice to access them during the assessment. At other times, he leaves the Schoology application to search for answers on Google.

But the most common cheating method described was people who take the test earlier sending screenshots to their peers who will take it later. This allows those taking the test later to memorize exact answers and study for specific questions.

With a click of the “send” button, students can forward information that gives others a special advantage – confident that their friends will return the favor when they can.

“When the test is on Schoology, my friends take screen shots of it,” said a junior girl. “This way I can know what’s on the test.”

Shalhevet’s poll matches other research showing that cheating is greater when the test is online.

According to a 2012 New York Times article, a study at Duquesne University concluded that the more online tools college students were allowed to use to complete an assignment, the more likely they were to cheat.

Tenth-grade Shalhevet Biology teacher Ms. Melanie Fine discovered this the hard way. Last December, sophomores took screenshots of Schoology test questions for the other class. Many students in the next class used the pictures to study.

“The other class had asked us for pictures of the test and we wanted to help our friends,” said an anonymous sophomore boy who participated. “We didn’t think it was a big deal because the test was harder than expected, and not many people had paid attention during class.”

During the same Biology test, students also Googled answers to questions, texted each other and looked at their notes for answers.

Ms. Fine, who is new to Shalhevet this year, learned what had happened from the administration. She responded by switching her next test to paper.

“I didn’t know the students,” said Ms. Fine. “I gave them the benefit of the doubt that they would do the right thing and not cheat, but that was a wrong assumption.”

Ms. Fine and her students agreed to drop that exam grade for one class and reduce its weighting for the other.

“Now I know that the best way to assess students is using paper,” said Ms. Fine. But she said that defeated the purpose of the iPads, which are required of all students in Grades 9, 10 and 11 and next year will be used by everyone.

“We need to find a way to make the iPad educationally useful but minimize the distractions it causes,” Ms. Fine said.

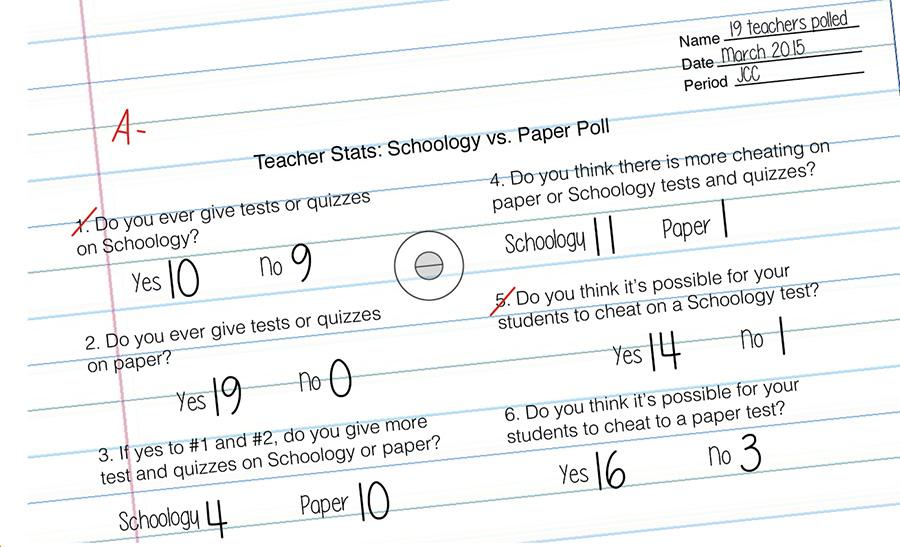

In a separate online poll of Shalhevet teachers, 52 percent said they had given assessments on Schoology. Teachers were invited to an online poll on March 8, and 19 out of 26 responded.

Freshmen, sophomores and juniors all reported that most of their assessments are on Schoology – not paper — particularly in Judaic Studies courses.

“About 85 percent of my tests or quizzes are on Schoology,” said sophomore Michelle Greenberg. “They’re usually online for English and Gemara tests.”

Students said math tests, on the other hand, are usually on paper, perhaps because math teachers want students to show their work.

Teachers who do use Schoology for assessments praised its convenience, efficiency and user-friendly interface that allows them to easily post comments on student work – though they seemed aware cheating was a problem.

“Schoology tests are quick and easy for teachers to use,” said Jewish History teacher Mr. Jason Feld. “And at the end of the day, cheating is a choice that harms the individual’s education.”

Judaic Studies teacher Rabbi Ari Schwarzberg also gives Schoology tests.

“Schoology doesn’t waste paper, it’s efficient and organized,” said Rabbi Schwarzberg. “Cheating is an age-old trick and I don’t know if not using Schoology will totally eliminate the problem.”

According to Schoology’s online support forum, Schoology users at other schools have also voiced concerns about online cheating.

“This is the single feature preventing me from using Schoology for all testing,” said Holly Hauck, a teacher who left a comment on Schoology’s online forum on March 6 of this year.

“My students can navigate to Google and search for each question if they want to. Having 30 students in each class, this is simply too much to monitor, and locking each individual iPad takes way too long.”

Two responses on a thread titled “Preventing Cheating,” offered suggestions to help avert it. One was to have students download “Casper Focus,” a program that locks students into a particular app for a set amount of time.

The other would be for a school to block internet access to all sites except for Schoology. This is possible if all students use the same school Wi-Fi network.

Another possibility would be to just ban Schoology tests. Teachers could still use the program for everything else it does, including attendance, homework, messaging and in-class projects.

But Shalhevet Principal Reb Noam Weissman believes Schoology assessments should not be banned— cheating or not.

“I don’t think the research indicates that we need to ban Schoology or online tests,” said Reb Weissman in an interview regarding the student survey results. Rather, it raises the question of why it is happening.

“We need to pinpoint the thing that’s causing this to happen, and then limit that thing,” Reb Noam said.

Next year’s General Studies Principal, Mr. Daniel Weslow, agreed.

“I don’t think banning Schoology assessments is the answer,” said Mr. Weslow in an interview. “It’s a conversation piece, but doing away with it doesn’t solve the problem. Shalhevet’s students are intelligent and creative, and if they want to cheat I’m sure they’ll come up with ways to do it.”

Not to say that cheating is only possible online— 20 percent of Shalhevet students said they cheat on paper by looking at their classmate’s work.

However, some teachers contend that paper exams are the safer bet against cheating, which is why 47 percent of teachers responded that they don’t give tests on Schoology.

“I cannot ensure that if I give a Schoology test that students won’t go online and look up information,” said Biology teacher Dr. Melissa Noel. “If I have 20 kids in my class, I can’t monitor them all at once.”

History teacher Mr. William Reusch has the same policy

“If I’m trying to test students’ ability to think for themselves, I feel like it would be too tempting to cheat on an online test,” said Mr. Reusch. “I’m going to do anything I can to prevent the temptation of cheating. The safest bet is using paper and pen.”

Sixty-two percent of students polled agreed that cheating on Schoology is easier than cheating on paper.

“It’s easier because it’s not obvious,” said a female student who had tried it. “You can easily switch from Schoology to your notes and there’s a much lower chance you will get caught.”

Although cheating is not as common on paper, teachers still guard against its potential threat: they use dividers, spread students throughout the classroom and create different versions of tests.

For now at least, aside from the honor system, there’s not much teachers can do to prevent online cheating.

And of course, many students do not cheat for personal and moral reasons.

In response to the survey, 40 percent of Shalhevet students said they’d never cheated at all.

“Cheating is not something I do,” said junior Sarah Mankowitz. “I think it’s unfair that people who cheat get a better grade than me, even if I studied really hard.”

“I think it is a negative. because it is immoral and you can’t cheat on life,” said freshman Zack Hirschhorn. “I don’t care what other kids do, as it doesn’t affect me. However, I will tell people not to cheat, but I won’t tell a teacher if they do.”

Cheating poses obstacles for students and school officials alike.

“I think that cheating is a chronic challenge across all disciplines in the world,” said Reb Weissman. “It does happen and our job is to educate students that, ethically speaking, it is not the way they should live their lives.”

But since no type of assessment is foolproof – and Schoology isn’t going away any time soon – for the time being, students who want to prevent cheating will have to rely on the one tool only they have: their own moral compasses.

Generation Cheat

Rose Lipner, Features Editor

From Stanford University to the SATs, cheating is prevalent in all parts of the country, at all grade levels and at all levels of academic talent.

Fifty-nine percent of American high school students admit to having cheated, according to a 2010 survey by the Josephson Institute Center for Youth Ethics.

And it’s not just failing students who resort to stealing others’ work. Cheating is also growing in top colleges and universities, where scandals make national news.

In 2012, 125 Harvard students were accused of cheating by working in groups on a take-home final exam, even though they were explicitly told to work alone. Sixty of these students were expelled.

Just last week, the Los Angeles Times reported on a Stanford scandal in which about 20 percent of the students in a Civil Engineering course were cited for cheating.

In 2011 on Long Island, 20 students from five schools— including two from North Shore Hebrew Academy, a Modern Orthodox high school— paid another person to take the SAT exam for them.

And at Corona del Mar High in Orange County, school officials last year expelled 11 students who had hacked into the district’s computer system to change grades and access exams.

As for everywhere else, just because no one’s been caught doesn’t mean no one is cheating.

“Cheating is everywhere— even at these Ivy League schools,” said Shalhevet junior Daniella Banafsheha. “While I’m a bit surprised that such students would cheat, it goes to show that cheating is now part of our culture. There’s not much we can do to stop it from happening.”

At Shalhevet, 56 percent of students say they have ever cheated on an exam, slightly less than the national average of 59 percent. Most cheated on Schoology, which is new; just 20 percent have cheated on paper tests.

But that’s small comfort to Dr. Jerry Friedman, who founded Shalhevet in 1992 with the specific goal of enhancing students’ moral development.

In an interview, Dr. Friedman was sympathetic – up to a point – toward students and the pressures they face.

“I’m not happy with the amount of cheating, but I understand it,” said Dr. Friedman in an interview.

“We’re dealing with human nature and excessive competition. We established Shalhevet to see if we could mitigate that problem as much as we can.”

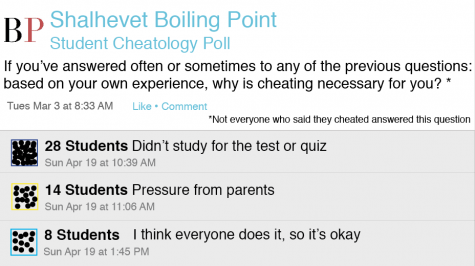

In anonymous interviews, students say they cheat because tests aren’t fair, they didn’t study or because it seems harmless.

Dr. Friedman rejected that logic.

“When you cheat,” he said, “you might get into a top college, but this one act has actually stopped your peers from getting into that school just because they followed the rules.”

He also rejected technology as an excuse.

“There’s no doubt that technology is making cheating easier,” Dr. Friedman said. “But the root of the problem is not in the technology, it’s how we’re raising our students.”

Still, technology seems to be playing a role. At Shalhevet, more than twice as many students say they’ve cheated on Schoology exams as on paper.

At Stanford, Provost John Etchemendy partially blamed technology in an e-mail about the university’s cheating scandal last month.

“With the ease of technology and widespread sharing that is now part of a collaborative culture, students need to recognize and be reminded that it is dishonest to appropriate the work of others.” Provost Etchemendy wrote, according to Stanford’s official website.

And while Shalhevet students had lots of justifications for their own cheating, they were much less tolerant of others’.

“The fact that students can cheat on a standardized College Board exam is pretty awful,” said a sophomore boy. “Some of those students who get into prestigious colleges are the people who may be leading our country or becoming doctors. Do we really want those people to be cheaters?”

At Harvard, Dr. Friedman wrote his doctoral dissertation about how schools can teach teenagers to be moral.

“We need to work more on saying: how fair is it that when you’re cheating, you’re really stopping someone else from getting that spot [for college]?” he said, adding, “If you’re cheating and it doesn’t bother you, then we really have a problem.”

Vanessa • Mar 10, 2021 at 6:22 am

Love this

Coach M • Jun 2, 2016 at 5:31 pm

I make my assessments timed so students actually do NOT have the time to go to other websites and look for answers or google to check word definitions or anything. If I write the exam, you should know the material. I never test on anything not covered and if I need a space waster question, it’s a made up one about me that the student’s can’t get wrong for a gimme point. 30 seconds is plenty of time to read a question and 4 multiple choice answers, especially if it’s a vocabulary word, definition is the same 4 times just the part of speech changes. The only part I had not timed, was matching. Questions are in random order and answers appear in random order as well. No 2 students are taking the same exam at the same time, so it doesn’t help them to look at their neighbor’s iPad. One has to actually know the material to be successful.

Kim C • Dec 15, 2015 at 7:47 am

We use schoology at our school. We have reduced the cheating problem by using LAN School which limits what the kids can access on their tablets. The ONLY internet I allow is Schoology. It can also limit apps. 🙂