EXODUS: Jewish population wanes in South Africa

Since the end of apartheid, the decline has slowed, but the community's warmth - and the rise of Mandela - have not been enough to keep Jewish South Africans from emigrating, many to Los Angeles.

January 19, 2014

Although Shalhevet did not formally commemorate the passing of legendary human rights leader and statesman Nelson Mandela, the five minutes in between class and Town Hall Dec. 5 were particularly quiet, as everyone was fixed on iPhones learning the news.

The former president of South Africa, known for his leadership against the apartheid regime and for guiding a peaceful transition to full democracy, had died at age 95 from a respiratory Infection.

“I grew up in our family home near the Atlantic Ocean and it overlooked Robben Island, so I was always aware of home and what he meant,” said History teacher Dr. Michael Yoss.

“One of the greatest experiences in my life was witnessing Mandela getting the keys to Oxford, because I realized just exactly why I had left South Africa and what he meant and stood for. I was standing there with people all over the world, and one doesn’t have to be South African to appreciate him. His values are universal.”

Dr. Yoss left South Africa in 1978 because he was opposed to the apartheid regime.

As Dr. Yoss asserted, Nelson Mandela was revered not only by the blacks he emancipated from strict rules that forbade them from living or working alongside whites, or by those who admired his endurance through 27 years of imprisonment on Robben Island near Dr. Yoss’s childhood home. His advocacy of peace and equality affected the world and reshaped the country of South Africa, including its shrinking Jewish community.

Although the Jewish population in South Africa is still the 12th largest in the world, it has declined by more than 40 percent in recent decades, similar to Jewish declines in Middle Eastern countries and Eastern Europe. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, South Africa’s Jewish population today stands at around 70,000, compared to 125,000 at its peak in the 1980s.

The exodus slowed after Mandela was freed, but Jews are still leaving South Africa at a rate of about 1,500 per year, heading for Israel, Europe, Australia and the United States. JTA.org, a Jewish news service, reports that many in the U.S. settled in San Diego, Irvine, and Los Angeles’ Beverlywood area, home to many students and staff at Shalhevet.

Unlike other places Jews have fled, however, South Africa has seen little anti-semitism. In interviews with the Boiling Point, expatriates who are part of the Shalhevet community described their home country as a place that most of them loved and some missed.

Executive Director Robyn Lewis was born and raised in South Africa, leaving at 18. Her family left because they were looking for “a safer, better life.”

She is still extremely fond of her country and says she constantly misses it. If it were not for her great life in Los Angeles with most of her family here, she would still love to return to South Africa, she said, and its “beautiful, inclusive Jewish community.”

“A lot of people who left to places like America and Australia have gone back, because they missed it and preferred their lives in South Africa,” Mrs. Lewis said. “Many people did leave, but I would say that the rate of people leaving now is not as nearly as great as it was before.”

Mr. David Mankowitz, father of sophomore Sarah Mankowitz — whose mother emigrated from Zimbabwe, just to the north — described South Africa’s Jewish community as Zionistic and very united.

“The Jewish community was always fairly small, but very strong and very vibrant,” Mr. Mankowitz said. “In LA, when there is a community event like a citywide support for Israel, you would get a small percentage turnout, whereas in South Africa the majority of people would go.”

Jaimee Brozin, a first cousin of junior Nicole Feder, is a 19-year-old South African living in Johannesburg, and has no plans to leave. She attended King David Primary School Sandton and then went to Yeshiva College Girls High, which had more Judaic classes and was not co-ed. Jaimee praised both schools, saying they gave her a substantial Jewish background and identity.

After high school, she went on to study occupational therapy at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, which she described as having an active Jewish life. A group like America’s Hillel, called the South African Union of Jewish Students, or SAUJS, “brings the Jewish vibe to campus.”

On Shabbat, Jaimee’s family attends Chabad of Illovo— located right next to their house.

“We are a very tight-knit community,” Jaimee said. “We all take turns inviting our friends over for Friday night dinner. We are privileged enough to have my grandparents living next door to me, and my cousins and aunt and uncle just down a street. So Shabbos is very much a family affair.”

Jaimee has grown up entirely in post-apartheid South Africa, and likes the diversity and constantly coming across different African cultures. Her family follows South African traditions like having braii, or barbecue, every Sunday lunch.

“Personally, I feel that living in South Africa has given me many opportunities,” Jaimee said, “from meeting different people from all walks of life to being able to give tzedakah to the many beggars on the street. As a Jew, one rarely encounters anti-semitism. So it truly is a great place to live.”

Jaimee’s friend, 18-year-old Elchanan Nudelman, has a similar background. He lives in the neighborhood of Glenhazel, the district of Johannesburg that contains the most Jewish restaurants and shuls.

On Shabbat he attends a Mizrachi shul on the Yeshiva College campus, which he described as vibrant, with over 100 Jews attending.

“On weekends I spend a lot of time with family and friends,” Elchanan said, “sometimes studying for exams and tests if need be and also watching sports. But generally Saturday nights are spent with friends at movies or partying, while Sundays are family and relaxing days.”

Why then, have so many Jews left? Most of Shalhevet’s South African expatriates left during the apartheid era.

“It was mostly people who had a good profession and were educated who could leave,” said Dr. Yoss. “And many of those Jews were opposed to the apartheid regime because they had been from Europe and Nazi Germany, so it makes sense why they were so against apartheid.”

Like Dr. Yoss and Mrs. Lewis, Mrs. Esther Feder left in the early 1980s, a decade before it was over. Mrs. Feder, mother of Nicole and a former Shalhevet board president, also spent her childhood in South Africa, but never intended to leave. She came to the U.S. for college, but stayed after marrying Nicole’s dad.

“The South African Jewish community was smaller and very homogeneous,” Mrs. Feder said. “Everyone stuck together and there was no split between Reform or Orthodox. Everyone was similar in how they practiced, which was very a traditional Judaism.”

Mrs. Feder was brought up fairly oblivious of the outer violence and commotion.

“You have to understand that all the newspapers and televisions were sanctioned and run through government,” Mrs. Feder said. “I was not as politically aware as I should have been. Nobody really questioned what was happening, everything was kept separate and you did not really pay attention, as ridiculous as it sounds now.”

Another South African native is Mr. David Mankowitz, father of sophomore Sarah, whose mother was born in the African country of Zimbabwe prior to moving to South Africa. Mr. Mankowitz stayed in South Africa even after university, leaving only in 1993, after he was married — and just as apartheid was ending.

He grew up in small towns and the coastal city of Durban, moving to Johannesburg later on.

“I think significant factors were uncertainty regarding the future of the country, and fear of potential violence,” said Mr. Mankowitz said.

“I think we could have stayed in South Africa and been happy,” he said, “but there was the possibility that our children would eventually want to leave, so my wife and I thought better to make a new home somewhere else.”

No former South Africans in the Shalhevet community left after 1993 — perhaps partly because of Mandela, who not only ended apartheid but managed the transition to majority rule without official retribution against white citizens.

But something else happened then that threatened South African society just when it was getting restarted. When apartheid ended, violent crime began to skyrocket.

The year 1994, when Mandela became president, was the worst year South Africa had ever experienced in terms of murder and crime, with 70 people murdered per 100,000 of population, according to frontline.org — totaling 25,000 murders that year.

A survey in 2000 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime ranked South Africa second per capita for combined assault and murder and first for rape during the years 1998, 1999 and 2000.

Conditions have gradually improved, but there is still a lot of violence in South Africa. Four of South Africa’s main cities — Cape Town, Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth and Durban — are ranked in businessinsider.com’s 50 most dangerous cities in the world as determined by homicide rate. The United States, despite being enormously larger than South Africa, has only three of the 50 cities: St. Louis, Detroit, and New Orleans.

South Africa’s government has hired more police officers, and between 1996 and 2011, its prison population grew by 52 percent. During 2013, South Africa was said to have had 16,000 murders, only the 9th highest in the world. But even in 2010 and 2011, South African News reports there were an average of 44 murders, 181 sexual offenses, 278 aggravated robberies, and 678 burglaries in the country every day.

According to the country’s Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, the crime is partly a result of inefficiency of the Criminal Justice System, as well as high levels of unemployment and what it calls “social exclusion.“

But both before and after the end of apartheid, Jews who departed their native country of South Africa cited violence, chaos, and political instability as reasons, along with opportunities and potential they saw in countries abroad.

“The high crime rate and violence in South Africa affects most citizens and extra caution must always be taken when out,” said Elchanan Nudelman. “So it definitely does a cause a sense of worry.”

Nicole Feder said her family knows several people who have been robbed multiple times.

“I do feel a sense of having to be constantly aware of my surroundings and more safety conscious than when I am here in LA,” Nicole said.

South Africa’s history is very similar to that of America and the rest of the New World. The first white settlement occurred during the late 15th century during the Portuguese exploration, and then the Dutch colonized the region in the 1600s. Jews had begun migrating to South Africa as early as the 1820s, when they were guaranteed religious tolerance.

The Jewish population multiplied by 10 between the years 1886 and 1914, as many were attracted to the gold rush. Most of the South African Jews arrived from Lithuania and headed to Johannesburg, which was coined by some as “Jewberg.”

Jews then played a key role in the growing diamond industry and some became prominent politicians. But anti-Semitism was at its peak in South Africa during the 1930s and ‘40s. Afrikaners — South Africans of Dutch descent — supported Nazi Germany.

The Quota Act of 1930 and the Aliens Act of 1937 aimed to prevent further Jewish immigration. But after the war, South Africa apologized and promised complete equality to the Jewish community.

After that, the Jewish community of South Africa maintained strong ties with both the South African government and the new state of Israel. The South African Zionist Federation was permitted to collect money to aid Israel, and South African Jews, per capita, were the most financially supportive Zionists abroad, according to Wikipedia. Israel and South Africa became close military and economic allies in the 1970s.

It was in the 1980s that nearly all of Shalhevet’s South African expatriates began to leave. Among those who stayed, despite their strong ties with the South African government, many Jews supported and helped lead the anti-apartheid movement.

Harry Schwarz, who had emigrated from Germany as a teenager to escape the Nazis, became one of the country’s leading voices against apartheid and is called one of the fathers of the new South Africa.

Schwarz was one of the defense lawyers during the Rivonia Trial — the trial which convicted 10 members of the African National Congress, including Nelson Mandela, for conspiring against the state. In that trial, all six of the white men who were arrested were Jewish.

“Jews were always on a much more liberal edge,” Ester Feder said. “Most Jews came from Lithuania and they were on the more liberal side of the spectrum, and many of the defense lawyers during the Rivonia trials were Jewish.”

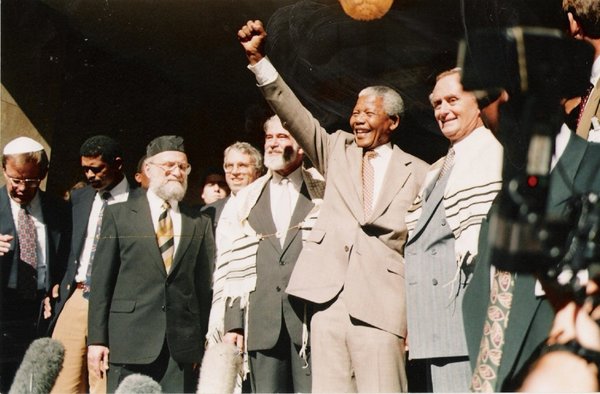

Mandela himself was born in 1918 and became was one of the more prominent members of the African National Congress, a movement founded to oppose apartheid. He was arrested in 1962 for his violent resistance, and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

He served 27 years in jail, primarily in Robben Island, and was released in 1990. Once freed, Mandela collaborated with then-President F.W de Klerk to abolish apartheid and the laws of apartheid began to fall.

In 1992, laws preventing blacks from living in suburban neighborhoods were lifted, and Mandela moved into the Jewish neighborhood of Houghton. According to jta.org, his neighbor was Jewish member of Parliament, Tony Leon, who greeted Mandela with a chocolate cake.

The country’s first multi-racial elections were held in 1994, and Mandela led the ANC to become president of South Africa.

According to JTA.org, on his first Saturday in office, President Nelson Mandela attended Shabbat services at Green and Sea Point Hebrew Congregation in Cape Town. He gave a speech in which he “appeal[ed] for the return of Jewish expatriates who left for security reasons.” This apparently did not materialize, though the departure of Jews dramatically slowed.

Mandela did not run for a second term in 1999, and spent the remaining years of his life focusing on his charity organization, the Nelson Mandela Foundation.

“He was an icon,” said Mrs. Feder. “An incredible man and an extraordinary human being.”

One reason Jews — and other whites — kept leaving was uncertainty about the economy. Mandela had been a communist, though he ended up encouraging private investment and South Africa’s economy continued to thrive.

Mr. Peter Feitelberg, father of alumna Ariela Feitelberg ’13, was one who was concerned. Born and raised in Cape Town — the legislative capital of South Africa and home to its second-largest Jewish community — for the first 23 years of his life, Mr. Feitelberg lived in a protected and sheltered environment.

Though he and his parents habitually protested against the apartheid regime, his chief concern was to “get a degree and leave the country” South Africa’s future was unpredicable. He left in 1984.

“Mandela advocated nationalization, his group were socialists and I am not for that,” Mr. Feitelberg said.

Mr. Mankowitz agreed.

“I think there was a lot of uncertainty towards what economic policies the country would follow,” Mr. Mankowitz said. “Would government take away things from people and give it to [nationalized] businesses? Ultimately, it didn’t really happen in South Africa, or at least not yet.”

When Mandela took over the presidency and apartheid was overthrown, tension grew between Israel and the South African government, which was suspicious of Israel because it had been so friendly with the apartheid regime. Nelson Mandela tried remaining close with Israel, and after his tenure as president, he visited the country in 1999 and stated, “Israel cooperated with the apartheid regime, but it did not participate in any atrocities.”

But he also warmly embraced PLO leader Yasser Arafat, and he and other ANC officials have compared Israel’s relationship with Palestinians to what Africans experienced under apartheid. When former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon died last week, South Africa did not send a wreath to his funeral.

For now, in South Africa itself, Jewish life continues to thrive.

The South African Board of Jewish Education, founded in 1929, is in charge of accrediting and coordinating Jewish schools, and has started the King David school system, with currently over 10 high school and elementary schools throughout the country.

Over 80 percent of Jewish children in South Africa attend a Jewish school, according to Jewish Virtual Library. Another website, maven.co, reports there are between 60 and 80 functioning synagogues throughout South Africa — though the Gardens Shul in Capetown, South Africa’s first synagogue, built in 1841, is now a Jewish museum.

And though the community is still declining, it is still very religious, with slightly over 80 percent of the Jewish population said to be Orthodox, and intermarriage at a mere seven percent, according to Jewish Virtual Library. That compares to a rate of 58 percent in the United States, as reported by jta.org.

As for the future, that seems to depend on stability, which, as Sarah Mankowitz stated, is the reason Jews left in the first place.

“A lot of people were unsure of what was going to happen and felt that there would be violence,” said Sarah. Crime is still a problem, she said.

Elchanan Nudelman predicted that three factors would cause Jewish South Africa to keep shrinking.

“Personally, I do not think the community will remain very strong over the upcoming years,” said Elchanan,

“Crime does play a major role in people leaving, and many people are not happy with the government,” Elchanan said.

“On the other hand many Jews here identify strongly with Israel, and therefore more and more Jews here are keen on making aliya. Another problem is that some Jews are assimilating, which also weakens the community.”

Mr. Feitelberg thinks the reason the Jewish population is still strong as it is is because many Jews are economically incapable of moving — and their numbers are being supplemented by immigrants from Israel.

But for now, many South Africans still feel as Jaimee Brozin does, at home in a warm Jewish environment within the diverse, now free society that was bequeathed to them by their own families — and Nelson Mandela.

“I love my country, and at the moment, I don’t ever want to leave,” Jaimee said.

This story won second prize in the Second Annual Jewish Scholastic Journalism Awards of the Jewish Scholastic Press Association.

Sherry • Jan 4, 2016 at 1:18 pm

I am trying to find the population figures for Jews in South Africa over the last ten years. All the articles I find stop in the late 90’s.