At the Skirball, a writer’s tale is told in art

Anita Brenner's books led a generation of Mexican artists to find their voice and break out from sterotypes

November 1, 2017

Walls of the Skirball Cultural Center are lined with works by 35 of the most important and famous artists in post-revolutionary Mexico. But what holds them together is the life of an unknown yet pivotal cultural figure who pioneered a modern vision of California’s neighbor to the south.

That figure is Anita Brenner — not an artist, but a writer, who greatly influenced many Mexican artists, filmmakers, and other authors. The Skirball’s Another Promised Land: Anita Brenner’s Mexico explores her life, and the role she played in revitalizing Mexico’s art through the artists she inspired.

It is at the Skirball until February 2018. General admission is $12 but free on Thursdays.

As a Jew growing up in Mexico and in Texas, Ms. Brenner, who was born in 1905 and died in 1974, experienced both anti-semitism and racism. This would later have a prominent effect on her ideology and artistic goals.

Having grown up with people telling her who she was, Brenner saw Mexicans’ need to have a voice of their own, and she was determined both to call out stereotypes and to educate an American audience about the beauty of Mexican culture.

Through essays, travel magazines and work with other artists, she dedicated her life to making this possible. Thus the exhibit is composed of works of those she influenced or brought to fame.

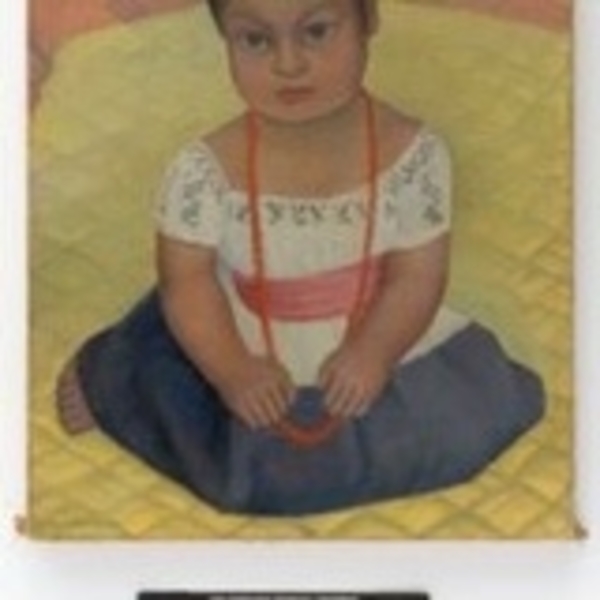

Among 150 pieces on display are works by the notable artists Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, Edward Weston, Jean Charlot and Frida Kahlo — all of them Brenner’s colleagues, friends or both. Together their works visually narrate Brenner’s life and contributions.

Orozco’s drawing “Tourists” fixates on the stereotypes of Europeans that Mexicans are weird and primitive. A scene of European tourists depicts them as large, frightening figures. Instead of looking at the country’s beautiful people and the vibrant culture, the tourists look away — as if to say that they already have notions of what Mexicans are.

The Orozco drawing is displayed next to a copy of Brenner’s book Your Mexican Holiday, which presents the beauty of the country’s landscape and the intricacy of its culture.

Visitors entering the exhibit start in a corridor with text and photographs detailing Brenner’s early life growing up in Mexico as the daughter of Latvian Jewish immigrants.

The exhibit then opens up to a visual timeline, composed of text, film and artwork, that wraps around the room. In the center of the room there sits a re-creation of a small cafe where viewers can sit at tables and read reproductions of letters from Brenner’s archive.

Emblematic of the exhibit, the subject matter of Jean Charlot’s “Idol” is a classic European female nude, but the figure expands to the edges of the canvas and takes an almost block-like shape, recalling ancient Aztec carvings; Charlot draws on Mexican heritage and evokes the power and eternality of their culture.

Brenner’s influence was felt in film as well. For example, in 1930, renowned Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein began his “Que Viva Mexico,” which, through editing and distinctive camera angles, attempted to connect ancient and modern Mexico. Eisenstein credited Brenner’s most famous pieces of writing, Idols Behind Altars, as an inspiration for the film. In the book, Brenner explores modern Mexican art along with ancient history and folklore.

The Skirball exhibition features a segment of Eisenstein’s film projected onto a wall.

The exhibit also explores similarities between post-revolutionary Mexican culture and the early culture of Israel. Posters from around this time stand out with bright colors and depictions of the beautiful Mexican landscape filled with strong farmers and workers — hearkening back to early Zionist art, which showed Israeli vitality in a very similar manner.

As the title of the exhibit suggests, Brenner recognized these similarities herself. She was a passionate socialist and was interested in kibbutzim. She used her observations of kibbutzim and the way they promoted themselves in her marketing of Mexico.

Overall, the show is very dense and not always straightforward. But it has a greater meaning than its individual parts. It is not just about the specific paintings, photographs, and film, but the context that Brenner’s life gave to them.

By using art to tell the story of a writer, it lets the audience in on the story of a writer who they have likely never heard of, and without having to read a whole book.

The work of Anita Brenner’s friends was a major factor in the realization of Mexico’s culture. Before the political revolution, the people of Mexico were told who they were — mostly other people’s’ stereotypes. But a new artistic revolution gave them the opportunity to create an identity for themselves, and share it with the world.

That a Jewish woman used her background of persecution to facilitate this is something all Jews can be proud of.